Donald Trump has now been impeached by the House of Representatives for the second time but will not stand trial before the Senate until after he has left office. Senate backers of the president seem to be coalescing around the argument that at that point their body will no longer have jurisdiction over the by-then ex-president.

The majority of impeachment scholars maintain that the impending trial is perfectly proper. An insistent minority urge the opposite. The arguments so far focus primarily on the text of the constitution and on three prior impeachments: Senator William Blount who, in 1797-98, was impeached while in office and tried afterward; Secretary of War William Belknap, who in 1876 was both impeached and tried after leaving office; and Judge West Humphreys, who in 1862 was impeached, tried, convicted, and disqualified a year after he abandoned his office to join the Confederacy. Although these impeachments provide persuasive precedent for post-term Senate impeachment jurisdiction, obsessing over them can mislead us because none involved a president. Even though Article II, §4, renders all “civil officers” (a phrase we now read to include judges and executive branch appointees) impeachable, the president was the nearly exclusive focus of all the impeachment debates at the Constitutional Convention.

The delegates supported the ouster of a president for personal corruption, egregious incompetence, and betrayal of the nation to foreign powers. But a singular concern of the Framers, not merely when debating impeachment but throughout the process of designing the constitutional system, was the danger of a demagogue rising to the highest office and overthrowing republican government.

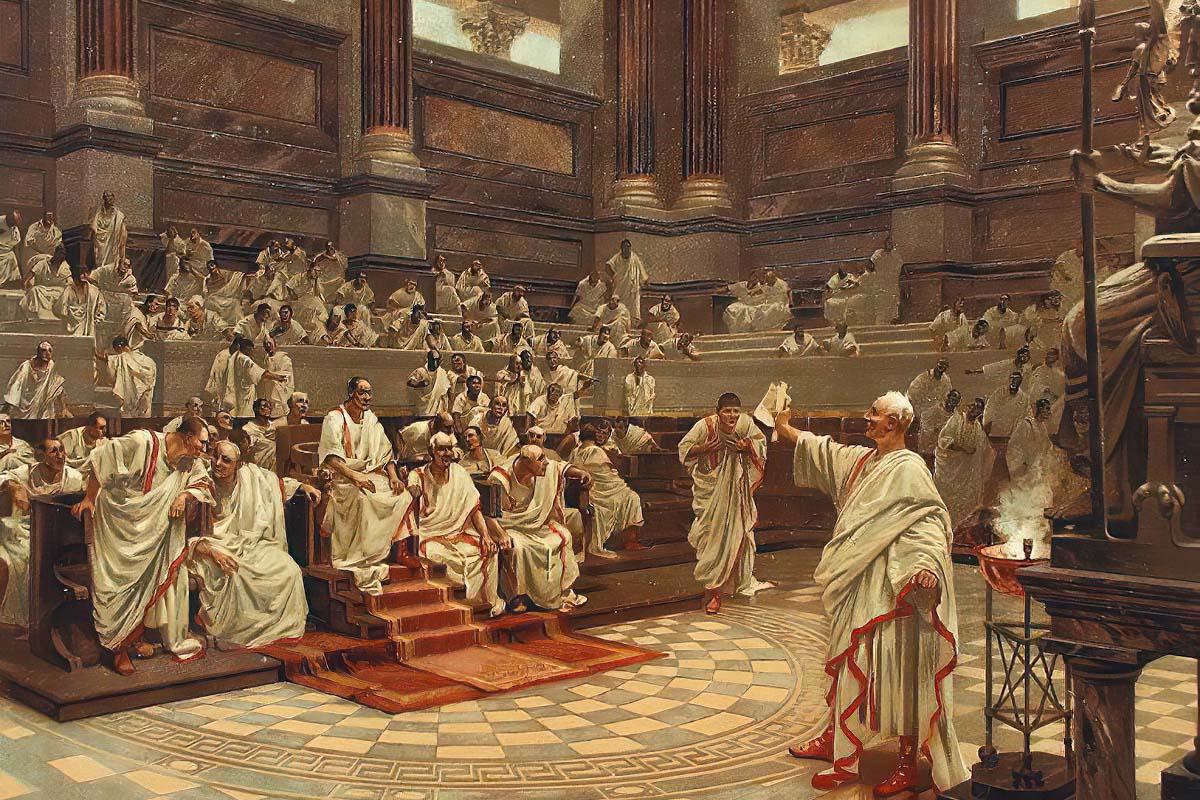

When composing our Constitution, the Framers drew on their educations and studied every historical model they could find. When crafting the impeachment clauses of the Constitution, they focused particularly on the constitutional history of Great Britain and the history of the limited number of prior republics, especially those of ancient Greece and Rome.

The unwritten British constitution was the Framers’ patrimony. In the wrenching process of resisting and then freeing themselves from British rule, they had studied and debated its every nuance. Likewise, the ancient history of Rome and Greece was the core of the “classical education” almost all the Framers possessed to one degree or another, and the educated members of the founding generation drew on their knowledge of it for inspiration and example. Their public and private papers are full of classical allusions. They commonly wrote under pseudonyms of Roman political personalities — Cato, Caesar, Brutus, Agrippa, Cincinnatus, and most famously, Publius, the pen name used by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay as authors of The Federalist Papers.

The impeachment mechanism written into the American Constitution owes its structure to a set of very specific lessons the Framers drew from British and classical history.

Impeachment was well known to the Framers as an invention of the British Parliament, crafted as a legislative tool for resisting royal oppression. Impeachment could not remove the monarch, but it could hobble a ruler’s aspirations by removing the ministers who were active agents of royal absolutism. For Parliament, the men most to be feared, who thus became the targets of the great political impeachments, were the hereditary aristocrats and landed gentry who were favorites of the Crown. But such figures could not be entirely defanged merely by removing them from office — even out of office, they retained title, land, wealth, and royal favor and might rise again to threaten constitutional order and, in the violent politics of the times, the very lives of the parliamentarians.

Therefore, the consequences of conviction following a British impeachment included the full range of penalties we would consider criminal – imprisonment, forfeiture of property and title, even death. These stern remedies were not merely retribution for wrongdoing, or even deterrent warnings to future officeholders, but prophylactic measures to ensure that the convicted officer could never again threaten constitutional governance.

The American Framers rejected monarchy, and they chose not to create an American aristocracy. Thus, the dangers against which the American rules of impeachment were directed were different. The Framers did not have to worry that an impeached and expelled officer would retain a hereditary title or landed fiefdom from which he could plot a violent resurgence. Nor did they have to worry that such a person would climb back into power by the grace of a hereditary monarch.

Moreover, they did not want the national legislature to act as a court, imposing personal punishments on either private citizens or erring officeholders. But they were every bit as conscious as the British that merely removing an officeholder from power would not necessarily neuter the threat such a person could pose to the Republic. The particular threat that haunted the founding generation was the demagogue.

The founders cautioned against demagogues constantly. The word appears 187 times in the National Archives’ database of the founders’ writings. Eighteenth-century American writers often used “demagogue” simply as an epithet to suggest that a political opponent was a person of little civic virtue who used the baser arts of flattery and inflammatory rhetoric to secure popular favor. In 1778, in the midst of the Revolution, George Washington wrote to Edward Rutledge complaining that, “that Spirit of Cabal, & destructive Ambition, which has elevated the Factious Demagogue, in every Republic of Antiquity, is making great Head in the Centre of these States.”

But the idea at the bottom of the insult was the Framers’ conclusion, based on the study of history ancient and modern, that republics were peculiarly vulnerable to demagogues – men who craved power for its own sake, and who gained and kept it by dishonest appeals to popular passions.

The Framers had ancient historical examples constantly in mind, particularly Cataline, who sought to overturn the Roman Republic by ingratiating himself with the Roman mob and raising an army to make him a dictator. His name was a synonym for anti-republican villainy in the minds of the Revolutionary generation, just as the famous Romans who thwarted him, Cicero and Cato, were the universally admired symbols of steadfast republican virtue.

Alexander Hamilton summed up the Founders’ view in Federalist No. 1:

History will teach us, that … of those men who have overturned the liberties of republics the greatest number have begun their carreer [sic], by paying an obsequious court to the people, commencing Demagogues and ending Tyrants.

The worry about demagogues influenced every aspect of the constitutional debate. For example, in proposing large, populous districts for members of the House of Representatives, Madison argued they would be less likely to elect demagogues.

The Framers’ fear of a demagogue was doubly acute because the new American chief executive would be chosen, not by hereditary succession, but the people. The much-maligned electoral college was devised, not only as a means of giving states a special mediating role in picking the president, but also with the idea that the state legislatures tasked with devising processes for picking electors, and the electors themselves, would be sensible statesmen immune to the popular intrigues of a demagogue.

However, the Framers expressly rejected the idea that periodic elections alone, even elections by the imagined body of discerning electors, would be sufficient proof against a president either corrupt or with aspirations to tyranny. Accordingly, they adopted impeachment, but with two major innovations from British practice.

The first was making the president, America’s head of state and chief executive, subject to impeachment at all. If a demagogue rose to the presidency, he could, upon displaying dangerous behavior redolent of autocratic ambitions, be removed. But Article I, Section 3, does not limit the consequences of conviction to removal. It goes on to permit “disqualification to hold and enjoy any Office of honor, Trust or Profit under the United States.”

This provision serves a critical function. Unlike British impeachments of old, impeachment under the federal constitution is not punitive. It is purely political. It seeks to protect the constitutional order in part by removing bad actors from federal service now, but also, where appropriate, by preventing them from rising to power again. Because the United States has neither a hereditary monarch nor a hereditary landed aristocracy, the officer removed need not be imprisoned or killed to prevent a return to national power. Permanent disqualification suffices. If personal punishments are deserved, those are reserved to the ordinary criminal courts.

How is all this relevant to the apparently technical question of whether a president may be tried after he leaves office?

The key to the Founders’ fear of the demagogue was not merely that he might secure high office, but that the means by which he would attain it – appeal to the mob – would allow him to corrupt or overthrow the Republic in order to transform himself into a dictator. The source of the demagogue’s power does not expire if he is expelled from office; so long as he retains the loyalty of the mob, he may return to power.

As concerned as the Framers were about the dangers of the demagogue, they imagined that they were protecting their new Republic in a variety of ways – including a presidential electoral system managed by state political elites and large House districts – that would defeat the wiles of such a person in an age when communication was limited to voice, letters, and newspapers of limited local circulation. Imagine their terror if told of today’s technology that allows the demagogue to appeal directly to millions through Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube.

Donald Trump is the living embodiment of the Framers’ fears, amplified many-fold by the reach of modern media technology. If there were any doubt that his departure from the White House will not alone end his threat to the national government, consider that, even now, after the failure of the January 6 assault on the Capitol and the chastisement of a second impeachment, Washington, D.C., has become a vast armed camp fortified, not against foreign invaders, but against Trump supporters still seeking to overturn the results of a free and fair election.

Trump was the man against whom the founding generation armed the constitution with the disqualification clause. They would surely think anyone quite mad for suggesting that a president who actively sought the overthrow of democracy could not be disqualified from trying again because the failed plot reached its crescendo too close to the expiration of his term.

The Senate trial of Donald Trump for inciting insurrection is entirely consistent with the founders’ original intent.