South of Salt Lake City, Utah, there’s an idyllic hilltop neighborhood called Suncrest. A master-planned community, hundreds of modern single-family houses stretch out across nearly 4,000 acres of canyons, trails, and Gambel oak trees. If you look in one direction, you see the adjacent mountains that include the ski resorts Alta, Solitude, and Brighton. In the other, you can see the wide expanse of the city. That’s part of Suncrest’s appeal: It’s only 15 miles from the largest city in the state, but it feels like a quiet mountain town.

It also happens to be the place that best illustrates the solution to America’s historically low voter turnout. The U.S. already has some of the lowest participation rates in the developed world. The new coronavirus threatens to make that problem even worse by turning the act of voting itself into a potential health risk.

While Suncrest feels like one community—it has one Mormon church and one restaurant—it’s divided into two counties: Salt Lake and Utah. In fact, the county line runs right down the middle of it. Both sides are similar in population size; each is 90 percent white. In the 2016 election, however, they had dramatically different voter turnout rates. Suncrest’s Salt Lake County residents showed up to vote at a rate nearly 18 percentage points higher than their Utah County counterparts, with about 81 percent of Salt Lake’s registered voters casting ballots compared to Utah’s 63 percent.

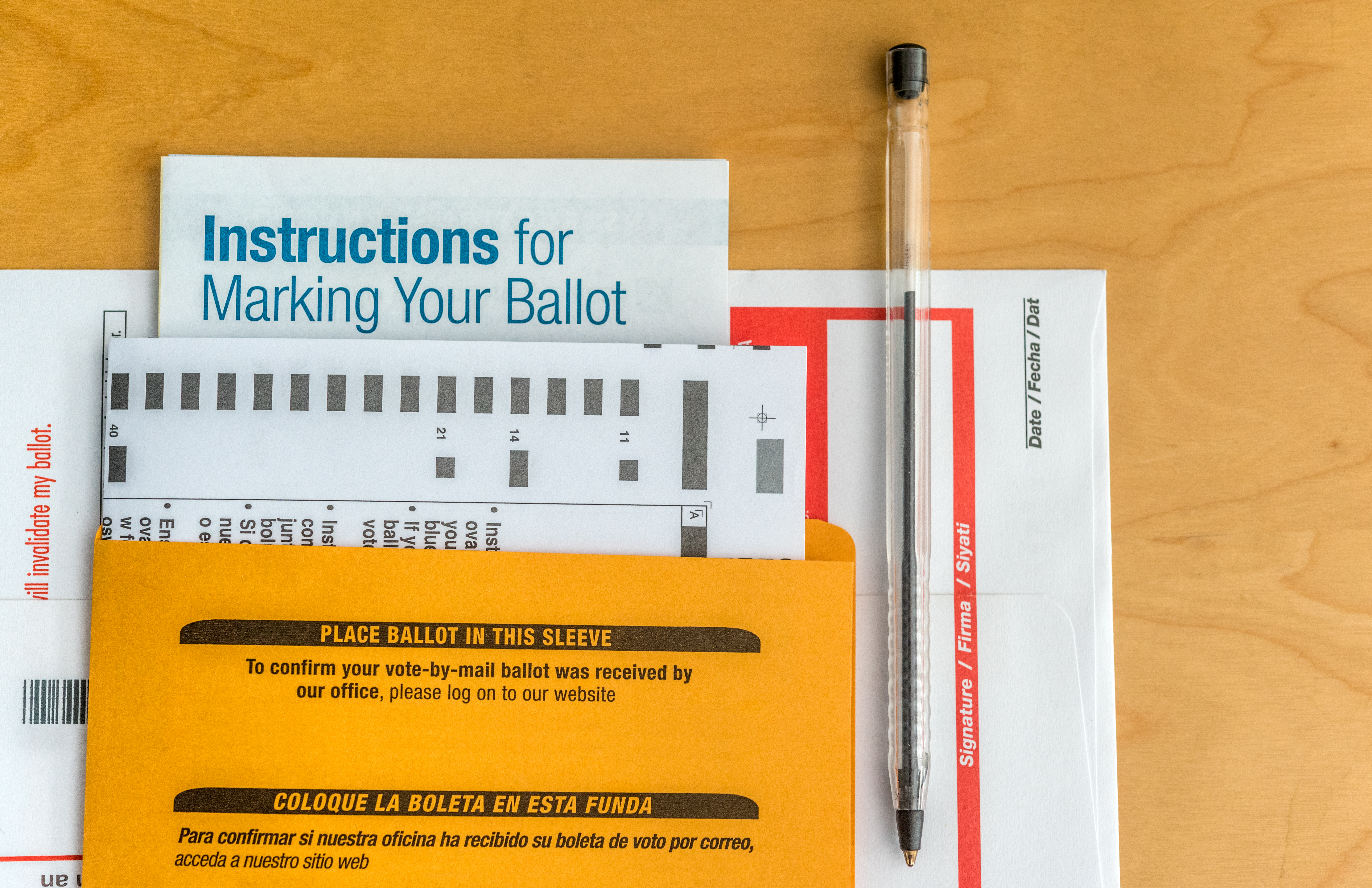

What made the difference? The two counties used different voting systems. Whereas Utah County stuck with the traditional model of people lining up at polling places to cast ballots, Salt Lake County switched to conducting its election entirely by mail. Under that system, otherwise known as “vote at home,” voters receive their ballots in the mail weeks before Election Day and can either mail them back or drop them off at a secure site. In other words, Suncrest, a demographically homogenous community, offered something no other part of the country has: a natural experiment to compare traditional voting to voting at home.

Usually, an electoral reform is deemed successful if it increases voter participation a few percentage points. The jump in Salt Lake County’s turnout was on a whole other level. And the disparity wasn’t limited to Suncrest. In that same election, 21 of Utah’s 29 counties had switched to vote at home. Those counties had an average turnout rate of nearly 9 percentage points higher than those that voted the old-fashioned way—and 5 percent higher than was predicted by a generally accurate turnout forecast, according to a study by Pantheon Analytics that was commissioned by the Washington Monthly.

Usually, an electoral reform is deemed successful if it increases voter participation by a few percentage points. In its first vote-at-home election, turnout in Salt Lake County surged by 18 percentage points.

The success of those counties led six of the remaining eight holdouts to try vote at home in the 2018 midterm election, including Utah County. Sure enough, Suncrest’s Utah side turned out 8 percentage points higher than it did two years earlier. Such an increase was especially unusual, given that midterms generally see lower turnout compared to presidential election years. Now, in 2020, Utah will run its first statewide election entirely by mail.

That has lessons for the rest of the country. For the past few presidential elections, national turnout has hovered around 55 percent of eligible voters; for the past few midterm elections, it has fluctuated from the mid-30s to the 50s. Before counties started mailing out ballots, Utah’s voter participation hadn’t been much better. But it addressed the issue, taking a cue from other states that were experimenting with vote at home to boost turnout.

In the process, Utah has not only shown how to get more people to vote. It has also demonstrated how to overcome the political resistance that electoral reforms inevitably run into: by allowing county election officials to opt in when they’re ready. Election administrators quickly found the system much cheaper and easier to run. Voters fell in love with the ease of mailing in their ballots.

Other states have also seen success with this opt-in approach. Colorado first tried vote at home for primaries and local races, before using it in all elections. Washington transitioned to vote at home on a county-by-county basis, and Arizona, California, and Montana are in the midst of the same process.

In California’s March 2020 primary election, Orange County used vote at home; 47 percent of its registered voters cast ballots. Los Angeles County didn’t; its turnout rate was far lower, at 29 percent. Part of the difference was that Los Angeles County was using new equipment that performed poorly and residents had to wait hours in line at the polls—issues that don’t arise when you vote at home. That’s why California’s secretary of state called on Los Angeles County to conduct its November election by mail.

If getting more people to vote isn’t enough, the outbreak of the novel coronavirus has made vote at home more essential than ever. The threat of the community-spread infection, which thus far has no vaccination or cure, could be more pronounced at polling places, where thousands of voters will stand close together in lines and put their hands on doorknobs, pens, and touch screens. Vote at home accomplishes two things at once: It takes away the threat of the virus spreading at polling places, and it mitigates the possibility that voters will not show up to vote out of fear of getting infected. For those who want to prevent a public health crisis from crippling a presidential election, the solution is already out there. It just also happens to have even broader lessons beyond how to vote during a pandemic.

That’s why Utah is so important: It shows the most politically palatable route to reform. Think of it like a business strategy. You start by giving customers a taste of a good product. Then, if all goes according to plan, they want more of it. In essence, Utah did precisely that by having its counties experiment with vote at home. They got voters hooked, simply by letting them try it out.

For much of the 20th century, Utah’s voter turnout had been a point of pride, regularly exceeding the national average. Then, in the 1980s and ’90s, its participation rate started to drop precipitously. In the 1980 election, for instance, it had a turnout rate of just over 65 percent. By 2000, when George Bush narrowly beat Al Gore, it had dropped to just below 55 percent.

But then two things happened that would ultimately set the stage for Utah to switch to voting at home. First, Congress passed the Help America Vote Act in 2002, after Florida’s infamous hanging-chad fiasco. The new law allocated funding for states and municipalities to upgrade their voting equipment and buy paperless, electronic voting machines. Those machines, however, would turn out to be costly, difficult to maintain, and plagued with security concerns.

Second, Utah passed legislation allowing anyone to receive an absentee ballot in the mail. Lawmakers were already concerned about Utah’s declining voting rate; they had been getting complaints from constituents that it was hard to leave work and go wait in line at the polls. Truck drivers might be out of state. Nurses couldn’t leave their patients. Even a state employee who helped run the elections reported that she couldn’t find the time to vote; she was busy fielding calls and coordinating logistics on Election Day. Meanwhile, the Republican Party suspected that this was keeping many of their voters from turning out.

So, in 2004, Utah changed the law. Before, people who wanted an absentee ballot had to prove they would be out of state. Only a narrow set of circumstances were deemed valid. But from now on, anyone could sign up to get their ballot mailed to them in advance—no excuse needed. Legislators may not have realized how consequential this decision would prove to be.

While more voters started switching to absentee ballots, turnout in Utah overall remained low. By 2009, then-Governor Jon Huntsman convened a commission to generate ideas to increase voter participation. The biggest reform to emerge was permitting online and same-day voter registration, said Rebecca Chavez-Houck, a former Utah state representative who was on the commission. Although that certainly made it easier to register, it didn’t succeed in getting many more people to actually vote. In 2012, only 57 percent of eligible Utah voters cast ballots, giving the state one of the lowest rates in the nation.

On top of that, the electronic voting machines, which had only been in use for eight years, were nearing obsolescence. The cost to buy new machines was exorbitant, and officials realized they would have to buy even more of them to reduce lines at polling places. Plus, reports at the time revealed that digital ballots are susceptible to hacking.

But one official had a solution. Rozan Mitchell, then election director of Salt Lake County, the largest county in the state, noted that since Utah had expanded absentee voting, one-third of her county’s voters were already signed up to receive their ballots in the mail—meaning a huge portion weren’t even using the machines that were so expensive to maintain. So, Mitchell argued, instead of spending millions of dollars to keep on doing things the same way—and getting the same lackluster results—the counties should conduct their elections entirely by mail.

In the face of the novel coronavirus, vote at home accomplishes two things at once: It removes the threat of the virus spreading at polling places, and it mitigates the possibility that people will not show up to vote out of fear of getting infected.

Oregon, she argued, had been doing it successfully for years. And indeed, as Mitchell noted, Utah was already using that system for a huge share of its voters. “It was like running two different elections,” Mitchell said. “You were running the vote by mail and processing those ballots, but you still had to facilitate polling places and [make] sure that you had all those fully functional. It really was truly administering two elections at the same time.”

As the idea percolated, county officials started nudging legislators to give them more freedom to try vote-at-home elections. Lucky for them, they were pushing on an open door.

State Representative Steve Eliason had been thinking along the same lines. A constituent had brought him election data from Oregon, piquing Eliason’s interest. The lawmaker then toured an Oregon county’s election offices and came home impressed with the success of the program. In 2012, he introduced a bill to give Utah counties the option to run all-mail elections. To his surprise, he faced little resistance from either party. Generally, Eliason said, any major change to election policy is hard fought, and it’s typically difficult to convince incumbent politicians to alter a system that has benefited them. In this case, however, both parties thought they had something to gain.

As a result of the 2010 census, there was a new congressional district that included liberal enclaves of Salt Lake City as well as nearby rural areas. According to party operatives on both sides, the state Republican Party thought that vote at home would boost turnout among older voters in the rural parts of the district, thereby helping the GOP candidate, Mia Love. The Democrats believed it might boost turnout among younger voters in and around Salt Lake City, helping Love’s challenger. “They both saw the value in it,” Eliason, a Republican, told me. “I can only assume they both thought it would give them some sort of strategic advantage.”

In March 2012, the Utah General Assembly passed the bill and the governor signed it into law.

But most county clerks felt there wasn’t enough time before the November elections to switch to an all-mail system. In the end, none of the counties in the new district embraced vote at home in that election, and Love lost.

Only one county opted in: Duchesne, a small and rural county in northeast Utah. The results there, however, caused the rest of the state to take notice: Duchesne’s turnout among active registered voters was 6 percentage points higher than the average for all Utah counties that election.

Generally, any major change to election policy is hard fought, and it’s typically difficult to convince incumbent politicians to alter a system that has benefited them. In Utah’s case, however, both parties thought they had something to gain.

Soon, other counties picked up the idea. The more they did, the more they discovered just how much people preferred to vote from the comfort of their homes. When Weber County, a small county in the northern part of the state, tried vote at home for a special library bond election in 2013, its turnout of active, registered voters nearly doubled compared to its 2011 municipal election. In fact, the turnout was even higher than it had been in the presidential election one year earlier. Nevertheless, the Weber county clerk, Rick Hatch, believed that vote at home made less sense for a national election. So, for the 2014 midterms, the county went back to the traditional system. “A few weeks before Election Day, our phone lines were inundated with people saying their ballots hadn’t come in the mail,” Hatch said. “When we told them we weren’t doing vote by mail this year, they got angry.” Only 38 percent of eligible voters cast ballots. Hatch got the message. From then on, Weber ran their elections by mail.

In the larger counties, however, there was more reluctance. Election officials were hesitant to force tens of thousands of voters into a new system. So Mitchell, the Salt Lake County elections director at the time, embraced the “try before you buy” logic, creating vote-at-home pilot programs for cities within the county. In 2013, two cities tried it. In 2015, nine did. At the same time, more jurisdictions throughout the state were voting by mail—and getting results. The cities and counties that used vote at home in their 2015 municipal elections increased their voter turnout average by 39 percent. After the success of those elections, Salt Lake County—the largest in Utah—made the decision to go all in, setting the stage for the Suncrest experiment.

As vote at home spread across the state, some people voiced concerns: How would they know their ballot had been received and counted? Would the system guard against fraud? What if someone tried to steal ballots?

Rozan Mitchell left her job in Salt Lake County and took the same position in Utah County in February 2019. While there have been no substantial instances of voter fraud or ballot theft in Utah—or in any other state, for that matter, that has converted to all-mail voting—Mitchell did say there has been one small trend of misbehavior unique to Utah: parents filling out their children’s ballots while they are away on their Mormon missions.

“A lot of the time, we’ll get the ballot back and we’ll look at the affidavit,” she said. “I look at it, and I go, ‘Huh, that doesn’t look like the way a Seth Johnson would sign his name.’ Oh, look at that, Seth Johnson is 19 years old. Let’s go look and see how his mother living in the same household signs her name. Oh, she has the same handwriting as this Seth Johnson signature.”

One of her favorite things to do, Mitchell said, is to call up the parents. Voting for someone else is illegal, she’ll say. “Did you know I can send him a ballot?” she’ll ask. “Did you know I can even email it to them?” Their reactions are priceless. “It’s kind of funny because here we have all these missionary moms and dads committing voter fraud for their child who’s out serving for their church,” Mitchell told me. “I love to freak the parents out.”

But the calls serve a purpose other than Mitchell’s amusement: While scary for parents, they made voters realize that their mailed-in ballots were not only being counted, but being confirmed as their own, either through signature-scanning technology or manual observation after an irregularity had been detected. “The more this system is used,” Mitchell said, “the more people’s fears start to dissipate.”

If you ask people who live in Suncrest, they’ll tell you they appreciate the new system. “I liked being able to just mail it in,” Julie Humphrey, a 61-year-old retiree, said. “I was able to look up the candidates and figure out what they stood for, because some of the local things, you don’t know what their platform is—you didn’t even know that they were running, honestly.”

Cory Jaynes, a 40-year-old project manager, agreed. “It was great,” he said. “[I] didn’t have to go to the polling place. Sometimes you go in there and you want to be able to research the ballot initiatives or the candidates. It was nice to be able to look them up. When you’re in a voting booth, you don’t really have too much of an opportunity to do that.”

In 2020, Utah will become just the fourth state in the nation to run a statewide all-mail election—after Oregon, Washington, and Colorado, all of which have seen higher turnout and savings to the taxpayers. Pew Charitable Trusts found that, since 2014, Colorado has saved $6 per voter. (Actually, Utah will tie for fourth with Hawaii, which will also run its first statewide vote-at-home election in November.)

Faced with the spread of COVID-19, it would make sense for other states to follow. For many, it’s too late to mandate vote at home statewide before November; many counties don’t have the specialized equipment or the trained workforce necessary to count and review vast numbers of mailed-in ballots, and won’t be able to build that capacity in the next eight months. By letting localities assess their own resources and opt in if they’re able to, states can reduce the use of polling places and allow more citizens to vote by mail without creating unintended breakdowns in the electoral system.

At the state level, there are other steps that can be taken. Beyond the five states that have transitioned completely to vote at home, twenty-nine states and D.C. already allow voters to request an absentee ballot regardless of circumstance. Governors and other state officials can help get out the word, encouraging people to request their ballot in the mail—or, better still, start proactively mailing absentee applications to every registered voter, as Ohio plans to do. And Congress can step in by providing funding to pay for postage and other costs. Oregon Senator Ron Wyden recently introduced a bill that would require every state to allow all voters to receive absentee ballots if 25 percent of states declared an emergency related to the coronavirus. It would also dedicate $500 million to helping state election officials meet the requirement.

Almost half of states already allow anyone to request an absentee ballot regardless of circumstance. Governors and other state officials can encourage people to request their ballot—or, better still, proactively mail absentee applications to all voters.

Allowing everyone to request absentee ballots, regardless of circumstance, is precisely how Utah got on the path to universal vote at home. “It’s voter driven,” said Amber McReynolds, CEO of the National Vote at Home Institute, an organization dedicated to expanding vote at home. “You give these options to voters and then they take advantage of it and then more and more people start using vote by mail and everyone starts to wonder, ‘Why should we keep rolling out these polling places all over?’”

This strategy of allowing voters and counties to opt in has proved more effective than mandating vote at home statewide in one fell swoop. Montana, for instance, tried to pass a ballot initiative to enact vote at home, but activists couldn’t garner enough signatures. Legislators in Alaska introduced a bill that would have mandated vote at home statewide, but it didn’t pass. (Since then, Anchorage conducted its first election by mail and saw the highest turnout in the city’s history.) Colorado’s 2002 ballot initiative likewise failed to pass. Advocates then switched to an incremental approach, and Colorado began experimenting with vote at home for primary and special elections. After seeing higher levels of turnout and saving money, the legislature successfully mandated that the practice be expanded statewide in 2014.

Historically, neither party has been willing to champion vote at home. Republicans have traditionally been resistant to reforms that make voting easier, and Democrats haven’t been convinced that vote at home gives them an edge in turnout. But COVID-19 has changed the stakes, and some states are moving quickly to allow more voters to cast their ballots from home. Alabama’s secretary of state, for instance, announced that self-quarantined voters can receive absentee ballots. New York’s Erie County will allow all voters to use absentee ballots for its presidential primary in April while the New York state legislature is considering a similar bill. And Connecticut’s secretary of state, Denise Merrill, asked the governor to issue an executive order loosening requirements on absentee voting. There are a handful of other states taking similar actions, and likely more to come, but it’s not clear how long the nonpartisan tenor of the push for reform will last.

That’s why, if the aim is to expand vote at home without creating a backlash, the opt-in model is most effective. “You can’t go from zero to 60 in a single election cycle,” said Phil Keisling, who implemented vote at home in Oregon as secretary of state in the late 1990s. “Every time a state has gone to a full vote-at-home system, it’s done so only after a number of elections in which the majority of ballots are cast this way.” The system has worked for Oregon, which had the fifth-highest turnout in the nation in both the 2016 and 2018 elections.

Of course, the most important determinant of election policy should always be what’s best for the voters themselves. And, as Utah shows, people clearly prefer voting from home—or, at least, they discover they prefer it once they’re given the chance to try it.

“I didn’t realize how important that was to some people, that they could take that ballot they got in the mail, sit down at the kitchen table, and really study out the issues,” Rozan Mitchell said. “I feel like vote-by-mail voters are much more informed than the average voter who would just show up on Election Day.”

In the U.S., the two greatest tragedies of the coronavirus outbreak are that the federal government waited too long to act and that a vaccine against the disease is likely a year or more away. Fortunately, neither is the case when it comes to elections. A proven solution is at hand. There is still plenty of time to roll out vote at home before the November elections—if we do so carefully, as Utah did.