We are sitting in the cheerful, cluttered kitchen of Adriana Fuentes, a self-described Army wife and mom who lives in Woodlawn Village, a military housing complex near Fort Belvoir, Virginia.

Fuentes is holding two paper finger puppets mounted on popsicle sticks, one with a sad face and one with a smiling one. She’s pretending to be her four-year-old son, Santana, as part of a role-playing exercise aimed at helping her teach her son about emotions.

“How did you feel when you scraped your knee?” asks Brenda Richards, a home visitor for Fairfax County Public Schools who’s playing “mom.” Fuentes holds up the frowning puppet, matching her own expression to the puppet’s. Richards asks another question, and this time Fuentes holds up the smiling one. The thirty-something Fuentes is wearing a Batman logo T-shirt and a practical ponytail – standard weekday wear for a busy mom. She’s outgoing, enthusiastic and plays her part with gusto. “What would be a patient face?” Fuentes asks Richards. “We talk about that a lot when he doesn’t get his way.”

For months, Richards has been a weekly visitor to Fuentes’s home, which Fuentes shares with her husband and children – four-year-old Santana, two-year-old Gabriela, and two teenagers. Richards typically comes during Gabriela’s naptime, but Gabby is awake today. She plays in the adjoining family room while Paw Patrol plays on the flatscreen TV. A big pile of moldable pink kinetic sand sits in a cookie sheet on the kitchen table, along with spoons and a small plastic shovel. Big wooden letters spelling “E-A-T” adorn the kitchen wall.

Richards works for the Home Instruction for Parents of Preschool Youngsters (HIPPY) program, a national home visiting initiative for low-income families that’s been offered in Fairfax County for more than a decade. A mom herself, Richards will visit half a dozen other homes this week, walking her clients through a tightly-scripted curriculum provided by the program, offering moral support and parenting advice. “What I love about my job is being a wife and mother and being able to support other mothers,” she said.

Richards pulls out a big plastic box she takes on all of her visits. The box is like Mary Poppins’ magical carpet bag, except it’s filled with props for this week’s activities, rather than a birdcage and a hat stand. On the agenda this week: making homemade “Play-doh” out of flour and salt, learning about gravity and recognizing shapes. Fuentes pretends to measure out salt and flour while Richards continues to play “mom.” “How does the salt feel?” Richards asks. “Rough,” Fuentes responds. “And how does the flour feel?” “Soft,” Fuentes replies.

Richards opens a container of pre-made clay to demonstrate math activities using the dough. They practice cutting the dough into two pieces, then four. “I wouldn’t have thought to do any of this,” said Fuentes, holding a plastic knife. “I wouldn’t know how to teach him.”

Like many of the roughly 285 families in Fairfax County served by HIPPY, the Fuenteses had initially applied for Head Start, whose waitlist in Fairfax County is 6 to 12 months long. Of the roughly 10,000 kindergarteners who started school in Fairfax County public schools this year, just 4,000 had preschool experience through state or federally supported programs, said Renee LaHuffman-Jackson, coordinator of the Office of Professional Learning and Family Engagement for Fairfax County Public Schools.

It’s an enormous gap that the county is hoping HIPPY can help fill, by teaching parents to ready their children for school, especially if traditional preschool options aren’t available. And it’s a concern that’s become increasingly urgent as the academic demands on students’ increase. “Kindergarten is what first grade used to be,” said Elisabeth Bruzon, HIPPY program leader for Fairfax County.

More broadly, programs like HIPPY could play an important role in shrinking academic achievement gaps between wealthier kids and poorer ones. While substandard schools, inadequate funding and indifferent politicians are all to blame for this inequality, growing evidence suggests the disparities also begin at home, with big differences in the kinds of resources and experiences kids get from their parents, depending on family income. Programs like HIPPY seek to level the home field — by teaching parents to be their kids’ first teachers — and evidence shows these efforts work. In the face of growing worries about inequality’s impacts, these programs could help create the opportunities low-income kids need.

A child’s “readiness” for school when she enters kindergarten — which includes knowing her letters and numbers but also how to pay attention and relate to her classmates — can affect her later achievement throughout her school career. One oft-cited 2006 study, for example, found that students’ early math and reading skills were powerful predictors of later school success.

Research finds that lower-income kids are increasingly less likely compared to their higher-income peers to be “ready” for school or to succeed. In fact, the gap in readiness and achievement between kids whose families are in the 90th percentile of income versus the kids in the bottom tenth (the so-called “90/10 gap”) is now wider than the black-white achievement gap that has long worried educators. According to Stanford University’s Sean Reardon, the differences in math and reading achievement between the richest and poorest students today is as much as 40 percent wider than it was for students 25 years earlier. As one result, lower-income kids are more likely to drop out of school and less likely to go to college. It’s a scenario that threatens to calcify, if not worsen, growing inequality while proving hollow the promise of education as a tool for social mobility.

Lack of access to high-quality child care and early education is one culprit behind these trends: in Virginia, for example, the average cost of center-based child care for a 4-year-old was $9,256 in 2015, according to the nonprofit Child Care Aware, while free programs like Head Start reach less than half of eligible kids. But growing evidence shows that parents are an equally important part of students’ academic success.

In one landmark study, published in 1995, researchers Betty Hart and Todd Risley spent two and a half years recording what went on in the homes of 42 families in Kansas for an hour a month. They found that the average child in a family with “professional” parents heard 2,153 words per hour, compared to 616 words per hour for a child on welfare. Over time, kids in professional families heard 215,000 words per week and 11.2 million words per year, compared to 62,000 words per week and 3.2 million words per year for kids on welfare. By age 3, the researchers concluded, the gap in language experience between affluent and low-income kids was as high as 30 million words, a difference that would carry over into the reading and writing skills of these kids in school.

Since then, other studies have found large and widening differences both in the amount and quality of time that high-income parents spend with their kids versus lower-income ones. College-educated moms, for instance, spend about 4.5 hours more per week on “child care” than moms with a high school diploma or less — even though college-educated moms are also more likely to be working outside the home, according to researchers Jonathan Guryan, Erik Hurst, and Melissa Kearney. Better-educated moms are also more likely to alter the composition of the time spent on their kids to emphasize “developmental” activities as their children grow.

New research by the University of Chicago’s Ariel Kalil finds that while low-income families are now more likely to own books and take their kids to the library than they were in the past, there are growing gaps between high-income parents and low-income ones when it comes to activities such as reading out loud, teaching kids their letters and numbers and taking them to the zoo, a museum or a play. Kalil and her colleagues say the differences are the result of higher-income parents investing more and more time and resources into their children. Researchers Garey and Valerie Ramey have dubbed this the “rugrat race” — an ever-escalating effort by middle-class parents to ready their kids for the high-stakes game of college admissions and, ultimately, jobs. It’s a race that lower-income parents, with far fewer resources, have little hope of winning. The result, writes Kalil and her colleagues, is “growing gaps in cognitive and non-cognitive skills, lower socioeconomic mobility and further growing inequality.”

Programs like HIPPY seek to solve the problem of the parenting gap at its source: at home. It’s an insight that HIPPY’s founder, researcher Avima Lombard, arrived at nearly half a century ago, on the other side of the world.

During the early to mid-1950s, North African and Asian immigrants were pouring into the new state of Israel from places such as Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco. Lombard, then at Hebrew University, saw that the Israeli-born children of these immigrants were struggling academically, despite attending preschool. She proposed what was then a revolutionary idea: home instruction for parents. “[P]erhaps we could find a way to bring changes into the home that would help prepare children to deal with the demands of school,” she would later write. The idea would be to teach parents how to impart the basic skills and knowledge their children would need to be ready for school. Moreover, directly engaging parents in their children’s education would invest them in their future success and keep them involved in the long term.

As a concept, home visiting was not new – home visits were a major component, for example, of the “Settlement House” movement in both Europe and the United States in the 1880s and 1890s, which sought to deliver nursing and other social services to the urban poor. These efforts, however, saw families as passive recipients of services, delivered by experts, intended to better their condition. Lombard’s innovation was to use home visits as a way to give parents their own sense of agency and capacity, as teachers of their children.

In 1969, Lombard launched a pilot program in Tel Aviv that, because of its success, would eventually be adopted nationwide in Israel. The program spread to South Africa, Germany, Mexico and other countries. In 1984, the program came to the United States, where it was soon discovered by the person who would become home visiting’s most ardent public champion: former Secretary of State and Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton.

As former President Bill Clinton told the Democratic National Convention last July, Clinton was impressed enough by the program that she invited Lombard to Arkansas to help establish a HIPPY program there. Today, the program is headquartered in Little Rock and has more than 30 sites in the state, according to Staci Croom-Raley, HIPPY USA’s Executive Director.

Clinton continued to champion HIPPY and home visiting more broadly as the Senator from New York. In 2009, she co-sponsored the Education Begins at Home Act with former Sen. Kit Bond (R-MO) to provide federal funding for home visiting programs. Ultimately, Congress created the Maternal, Infant and Early Childhood Home Visiting Program (MIECHV, or “Mc-VEE”) as part of the Affordable Care Act, which provided $1.5 billion in federal funding for home visiting. In 2015, Congress reauthorized the program as a stand-alone effort for two years, through fiscal 2017.

During her campaign, Clinton advocated doubling federal funding for home visiting programs to expand their reach yet more, and there’s little doubt that had Clinton become president, HIPPY and home visiting would quickly have become household ideas. It’s only one in a long list of what-might-have-beens had the 2016 election turned out differently.

HIPPY in fact relies on a peer-to-peer approach of moms teaching moms. It’s also a model that holds down costs. Not only is there no child care center to maintain — no rent, utilities or maintenance for the county or school district to pay — there are no high-priced Phd educators, social workers or nurses.

Under President Donald Trump and a Republican-controlled Congress, the prospects of home visiting programs are less certain. But there’s also plenty about these initiatives for both liberals and conservatives to like.

For one thing, they work. In September 2016, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) published findings from its “Home Visiting Evidence of Effectiveness Review,” an exhaustive survey of the research around home visiting programs. The report identified 19 different home visiting models, including HIPPY, that qualify as “evidence-based” and that provide multiple benefits to families, including better child and maternal health, “positive parenting practices,” and improvements in school readiness.

The HIPPY program itself has been through multiple evaluations over the last 20 years, and studies have found modest but consistent effects on school readiness and parenting practices. In one 2011 study, researchers found that Latino third-graders who had participated in the program had much better math scores than other Latino children who had not and that parents who had gone through HIPPY reported higher levels of “self-efficacy.”

One way in which HIPPY imparts that self-efficacy is through the detailed walk-throughs of the curriculum that home visitors provide. The HIPPY curriculum is highly scripted — home visitors literally read a script for each week’s activities word for word, which their clients will then follow, also word for word, with their kids. In addition to a detailed packet each week, families get nine books over the course of each year of the three-year-long curriculum, with activities tied to the content of the books. Each year’s curriculum lasts 30 weeks.

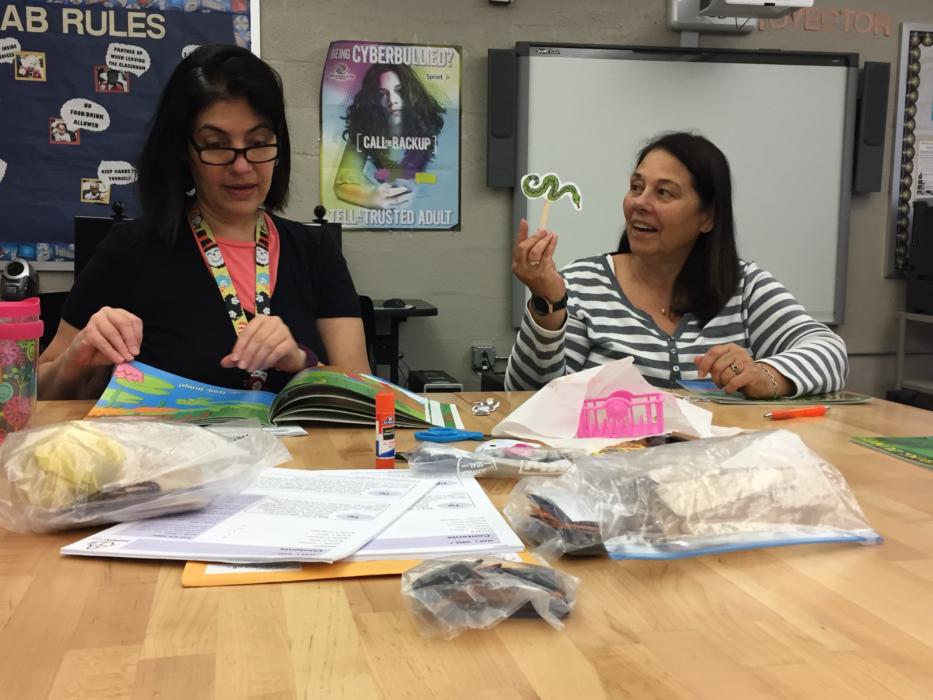

At a group meeting of HIPPY moms at the Markham School Age Center in Fort Belvoir, home visitor Betty McMenamy is reading out the script for that week’s activity. “In the math activity this week, you will do an activity that requires your child to cross the ‘midline,’” she reads. “This begins as early as infancy when a baby passes a toy from one hand to the other hand to cross their midline, and it’s necessary for reading and writing.”

“That’s interesting,” chimes in Natalie Ray, the mother of three-year-old Hailey, one of four mothers who are regulars in the group.

“In one of the activities today you’re going to focus on that,” McMenamy continues. “They’ll be drawing circles, and they will cross the midline.” Later on in the session, the moms in attendance practice drawing big, swooping circles in the air with their arms and work on counting circles from a set of plastic shapes.

“The scriptedness preserves the fidelity of the program,” says HIPPY USA Executive Director Croom-Raley, and allows for non-experts to be effective coaches and home visitors. HIPPY in fact relies on a peer-to-peer approach of moms teaching moms. It’s also a model that holds down costs. Not only is there no child care center to maintain — no rent, utilities or maintenance for the county or school district to pay – there are no high-priced Phd educators, social workers or nurses. As a result, administering HIPPY costs about $2,500 per child on average nationwide, Croom-Raley says. In Fairfax County, says program leader Elisabeth Bruzon, the program costs less than $1,500 per child and is free to participants. Overall, the Fairfax County HIPPY program cost $370,000 this year, with $20,000 coming from county funds and the rest from federal grants.

Credit:

Back in Adriana Fuentes’s kitchen, home visitor Brenda Richards is showing Fuentes how to make a “parachute” by tying a small plastic trinket to the handles of a plastic grocery bag with a piece of yarn. She tosses the grocery bag in the air, which drifts slowly to the kitchen floor. They will use this parachute in an exercise about gravity, comparing how quickly it falls compared to a crumpled wad of paper.

Next, Richards pulls out a slab of cardboard — clearly once part of a delivery box — in which she’s cut out three big holes: one in the shape of a triangle, one in the shape of a circle and one in the shape of a square. She also pulls out three “bean bags” — made by sealing rice into Zip-lock sandwich bags and then taping them into squares. All the props for HIPPY activities, Richards says, can be made with household materials. “You don’t have to spend money to teach your child,” she said.

Richards sets up the piece of cardboard on the kitchen floor, and now Fuentes plays “mom,” instructing Richards to throw the bean bags at the triangle-shaped hole, then the square. “I thought the roleplay was silly at first,” says Fuentes, “But it’s a really big part of the program. She’ll challenge me as if she were him so that I will be prepared for that moment.” Throughout the session, Richards as “Santana” makes deliberate mistakes, so Fuentes can practice how to correct him. “It’s a very gentle method of teaching,” as HIPPY coordinator Elisabeth Bruzon later put it.

Because child care centers focus on the child, what a child learns in school stays at school, in the absence of parent interest or participation. Programs like HIPPY directly engage parents, which can result in far broader impacts. It’s another aspect of the program that home visiting proponents like.

“What we learn we use all day long,” said mom Adriana Fuentes. “The program supports you and guides you as a parent, and I can tell how it’s been incorporated in our lives.”

For instance, Fuentes says, the lessons she’s learned through HIPPY have also helped her husband interact with their son. “And Gabby does some stuff now,” she said. “She’s counting because he’s counting, and she’s not even 3.” She also credits the program with smoothing her transition to full-time mom, something that happened when the family moved to Fort Belvoir from Detroit a year and a half ago. “It’s helped me with my self-esteem,” she said.

Sometimes the effects are even more profound.

Karla Merida, another Fairfax County home visitor, was herself a HIPPY client before joining the program as an employee. Merida, who immigrated from Bolivia in 2006, said she spoke no English when she came to the States. “I always stayed in the house and had few opportunities to speak to other mothers,” said Merida, who is slim, soft-spoken and still speaks with a heavy accent. Her home visitor became her lifeline to her new world, encouraging her to learn English while also teaching her how to work with her then three-year-old daughter, Emily. “She believed in me,” Merida said. Today, Merida works with 11 other moms as their home visitor.

Of course, home visiting programs like HIPPY are not a panacea.

Despite increasing interest and support in this approach, the programs are still tiny. From 2012 to 2015, the number of families served by home visiting programs jumped from 34,180 to 145,561, but that’s barely a sliver among the more than 4.6 million children ages four and under living in poverty in the United States. HIPPY, one of the country’s biggest home visiting programs, serves 15,000 families nationally.

Another limitation of home visiting programs is that they are voluntary, which means that many of the families with the greatest needs might not be reached at all. In the case of HIPPY, the program also requires a fair amount of commitment from the participating moms. Fairfax County program leader Elisabeth Bruzon said that nearly a fifth of moms who sign up for the program drop out in the first couple weeks when they see what’s expected of them. But she also said that nearly 90 percent of the moms who last three weeks stay with it through the end of the year.

Among these moms is Natalie Ray, the mom at the Markham Center group session.

“I have another daughter, and I wish I could have done this with her too,” Ray said. “She didn’t go to preschool so I feel like she wasn’t as prepared as other kids when she went into kindergarten. I feel like this would have helped her.”