His brand is law and order, but his criminal transgressions are on public display. His supporters don’t care.

He seldom sets foot in church and boasts of his extramarital conquests. His base is devout and adores him.

He has been diagnosed with antisocial, narcissistic personality disorder. The psychiatric report described him as “unable to reflect on the consequences of his actions,” displaying “gross indifference, insensitivity and self-centeredness,” as well as a “grandiose sense of self-entitlement and manipulative behaviors,” and a “pervasive tendency to demean, humiliate others and violate their rights and feelings.”

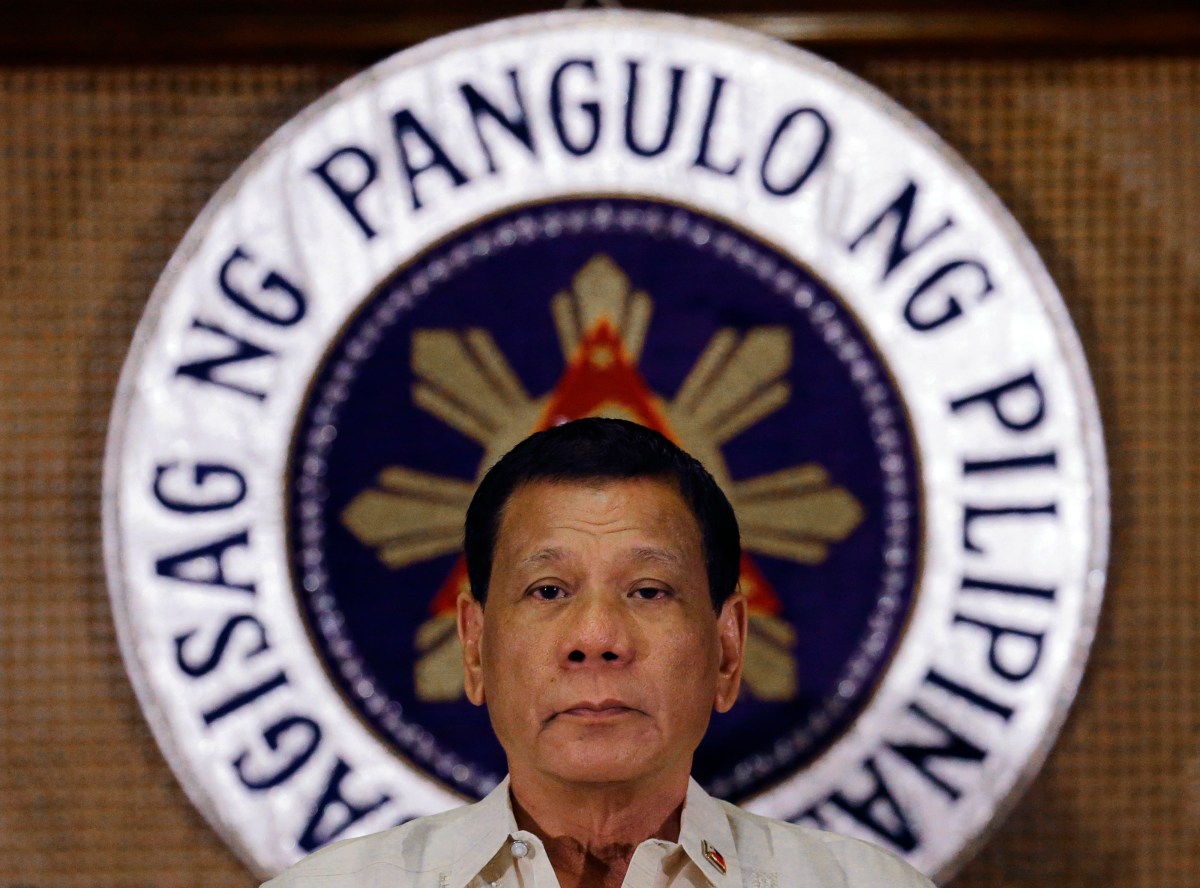

Throughout his tenure, Philippines President Rodrigo Duterte has often been compared to Donald Trump, and for good reason. (The psychiatric profile of Duterte is real.) But the 77-year-old’s six years in office—in which he waged a brutal extralegal war on drug cartels, Muslim insurgents, and innocent victims, costing an estimated 12,000 lives—are a reminder that strongmen may leave office. Still, the public’s desire for them hardly evaporates. On June 30, Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos, the son of the 20th-century dictator (Ferdinand) and equally famous shoe-fetishist (Imelda), will take the oath of office as president of this island nation of 110 million. It’s unclear yet to what degree his presidency might resemble Duterte’s or his parents’. The Marcos dynasty is known more for its kleptocracy than its autocracy, although (as the Trump clan has also shown us) the traits frequently go hand in hand.

Perhaps Bongbong will turn out to be less venal and brutal than his parents. He has yet to return a peso of the $10 billion reportedly looted by them, but he comes to office without the track record of sheer brutality and unapologetic cruelty of Duterte. The elder Marcoses were grifters, and they became dictators in large part to protect their grifts, but they never enjoyed the deep, populist connection with the Filipino voters that Duterte has forged. Examining the source of Duterte’s power may offer some clues about the future of democracy in the Philippines—and America.

Duterte got his start in politics in the southern city of Davao, the country’s third most populous metropolis and a hotbed of political violence generated by and against Muslim and Communist insurgencies. (Ironically, Duterte was appointed to his first leadership post in Davao by Corazon Aquino, who led the People Power Revolution that toppled Marcos in 1986.) As mayor, Duterte targeted drug dealers and users; some 1,400 of them (many just preteens) were reportedly killed on his watch. Duterte later bragged that he himself executed three suspects. After Duterte was elected president in 2016, he encouraged police to follow his example: “In Davao, I used to do it personally. Just to show the guys that if I can do it, why can’t you?”

The lawyer ran for president on a shoot-first-ask-questions-later platform, vowing that his term would be “a bloody one,” and that he’d pardon soldiers or police who violated inconvenient laws. He pledged to “litter Manila Bay with the bodies of criminals.”

Duterte kept his campaign promises. According to Human Rights Watch, some 7,000 extrajudicial killings were reported in the first year and a half of his term, with the pace initially running at a thousand bodies a month. He said he’d be “happy to slaughter” three million drug addicts. When his son Paolo was accused of smuggling $125 million worth of crystal meth from China, Duterte said, “My order is to kill you if you are caught. And I will protect the police who kill you.” (The case against his son was conveniently dropped.)

According to UN statistics, the Philippines had less of a problem with narcotics than the global average, and its drug usage rates are now about the same as when he was elected.

When Trump had his first substantive phone call with Duterte in 2017, State Department briefers urged him to condemn extrajudicial killings; but Trump had other ideas. “I just wanted to congratulate you because I am hearing of the unbelievable job on the drug problem,” the president said. “Many countries have the problem, we have a problem, but what a great job you are doing, and I just wanted to call and tell you that.”

Since then, the two leaders have had a shared a fondness for Vladimir Putin (Duterte has referred to Russia’s leader as his “idol”), a shared antipathy for Barack Obama (Duterte called him a “son of a whore”), and a shared hatred of the press. Duterte warned reporters in 2017, “You won’t be killed if you don’t do anything wrong.” The two men also share a view of gender relations: When Duterte’s wife accused him of decades of marital infidelities, he gleefully boasted of them. When an Australian missionary was kidnapped and raped in the Philippines, Duterte noted that she was his type and jokingly complained that he “should have gone first.”

While his American counterpart never won the support of even half of the electorate, Duterte once enjoyed a whopping 91 percent approval rate. Also, unlike Trump, he is voluntarily leaving office: The constitution requires that presidents serve a single six-year term. He remains overwhelmingly popular, and if not for term limits, he’d likely have won reelection without breaking a sweat. But few expect him to leave the political scene for good: Duterte entrusted his political legacy to his daughter, who takes the vice presidential office this week. Duterte himself might well find an extra-constitutional way back into office.

Why do so many Filipinos support a leader who seems to be so self-evidently horrific? The most straightforward answer: They see Duterte as their bold tribal leader. And if people like me can’t appreciate that, it’s because we belong to very different tribes. Law and Order is a device to police the line between Us and Them. An elected demagogue like Duterte or Trump expresses the tribe’s true character. He’s fallible, flawed, one of us. And his appeal is that he can say and do things that the rest of us can’t.

Consider religion. The Philippines is one of the world’s most devout Roman Catholic nations, and more than four-fifths of the population profess the faith. So how does openly nonobservant Duterte enjoy popularity on par with Pope Francis—whom he referred to as a “son of a whore” (the same epithet he hurled at Obama)?

It may be that his followers want someone to speak the unspeakable. Duterte is quite public in claiming to have been sexually abused by a priest as a teenager. (The claim is unproved, and the priest in question died in 1975—but the Catholic Church paid $16 million to settle sexual abuse suits brought against him by other victims in Los Angeles.) When Duterte bashes the Church, he speaks for many Filipinos who feel they’ve been abused or ignored by it or perhaps have simply run afoul of its strictures on divorce, abortion, or homosexuality. (Duterte makes homophobic remarks, but is widely seen as being more personally tolerant than many other politicians.)

The contradictions of Duterte are the contradictions of Trump. The contradictions aren’t a side issue; they are the issue. How can he do this? Because most of his countrymen want him to. And they want him to do so because the Law is for Them. And he is for Us.