For centuries in America, a class of persons was regarded as a servant caste whose duty was to work for the benefit of others and not themselves. That duty was bound up with a complex legal structure that closed off avenues of escape to ensure they did the work they were expected to do. Their bodies and lives were subjected to totalitarian control.

The service in question was enforced in some states but not others. Many thought that the laws imposing the service were human rights violations and sought to help the victims get away. The states that imposed the service sought to criminalize the rescuers.

At the core of the dispute was the physical control of some people’s bodies by others. The system of bodily control was based on entrenched structures of inequality that deemed some bodies intrinsically instrumental, markers of social and political inferiority.

The states that did this insisted that it was their prerogative to decide whether to make this imposition on some of their residents and that outsiders had no right to interfere. They argued that this was an issue of federalism and states’ rights. Each state could address the issue in its own way.

I just described America before the Civil War, and I have also described the country today, riven by the issue of abortion. The constitutional difference between the two times is that, in 1866, we amended our Constitution to guarantee that Americans would henceforth control, at a minimum, their own bodies. Yet here we are.

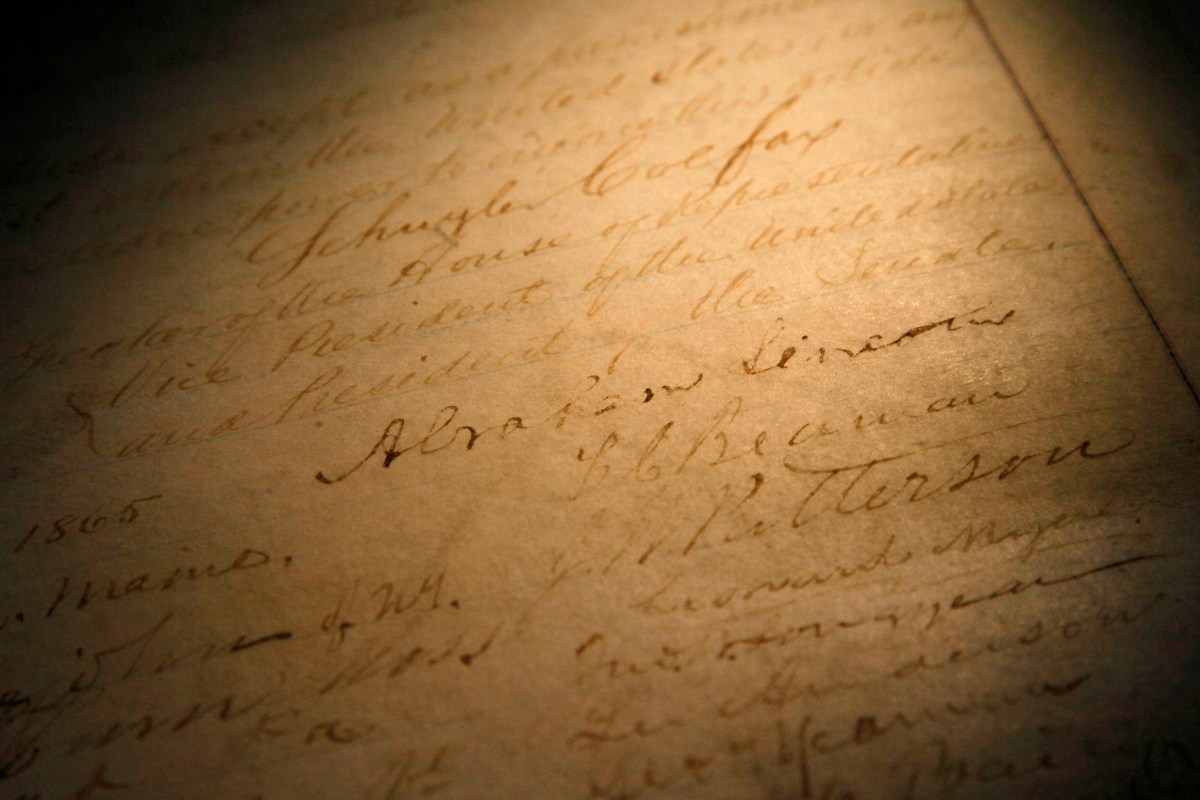

Defenders of abortion rights have been persistently embarrassed by the apparent fact that, as Justice Antonin Scalia wrote, “the Constitution says absolutely nothing about it.” The Supreme Court relied on that apparent silence when it trashed abortion rights in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health. But in fact, the Constitution has a lot to say. Before the Civil War, America routinely forced enslaved women to bear children, and it then amended its supreme law to ensure that no one could ever again be treated this way. The right to abortion is protected by the Thirteenth Amendment, which abolished slavery.

Roe v. Wade is an unpersuasive opinion. The root of its unpersuasiveness is the Supreme Court’s failure to ground its decision—that abortion is a fundamental right—in the text of the Constitution. Roe held that the right to an abortion resided within the Fourteenth Amendment, which through previous rulings, guarantees a “right to privacy” that would be violated by anti-abortion laws. Today’s conservative Court gleefully seized on the attenuated nature of that argument, noting that nowhere does the Constitution mention the word “abortion.”

Abortion defenders’ most common response to Roe’s weaknesses is to rely on the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, which the Supreme Court has interpreted to guarantee the equality of men and women. The Court in Dobbs casually dismissed this claim on the silly ground that laws that single out and hurt pregnant people do not discriminate between men and women. But the more fundamental weakness of an equal protection argument is that it treats this massive invasion of liberty and equality as though the fundamental wrong were one of unfairness. A better argument would focus on the physical oppression of losing control over one’s body. Once more, this is not the first time America has done this to some women.

The poor reasoning of a judicial decision recognizing a right does not mean that the right doesn’t exist. Brown v. Board of Education is a similarly weak opinion. It posits that black children believed segregation’s message of inferiority (they didn’t) and that this “sense of inferiority affects the motivation of a child to learn.” It has since become common knowledge that the problem was not Black fragility but the vicious racism of the southern system—about which the Brown Court maintained a diplomatic silence.

The textual support for abortion is present in the Constitution, but it has been neglected. The Thirteenth Amendment prohibits seizing and controlling people’s bodies. Compulsory pregnancy is part of the wrong of slavery that the amendment aimed to restrict. The argument is not an analogy. This was, for half the enslaved population, what slavery was.

A body of settled law interprets the Thirteenth Amendment, and it bears directly on the abortion question.

The injury of compulsory pregnancy has both individual and social aspects. Forced pregnancy is a deprivation of individual liberty. That deprivation is selectively imposed on women—and women are a group traditionally regarded as a servant caste whose powers (unlike those of men) are properly directed to the benefit of others rather than themselves. Compulsory motherhood deprives women of both liberty and equality. And the Thirteenth Amendment argument responds to both of these injuries.

Each has been the basis of longstanding rules of law laid down long ago by the Supreme Court. One line of cases holds that a person cannot be compelled by law to serve another, even if the service is purportedly required by a contract. Another holds that the amendment prohibits relics of slavery, authorizing Congress to, for example, prohibit racist housing discrimination.

The amendment is both libertarian and egalitarian because the paradigmatic violation deprives its victims of both liberty and equality. It compels some private individuals to serve others and does so as part of a larger societal pattern of imposing such servitude on a particular caste of persons. If the libertarian and egalitarian rules of the decision are plausible readings of the amendment, it is because each stresses one undeniable aspect of the paradigmatic case. While the amendment has been construed broadly to encompass both compulsions of individuals and the subordination of groups, each involves only one of the two main aspects of what the amendment forbids. Compulsory pregnancy involves both. Since the amendment reaches far enough to forbid either of these injuries, it undoubtedly prohibits laws that inflict both at once.

The argument concededly has limitations. All constitutional rights sometimes yield in the face of a compelling state interest. The states, defending their restrictions, will say that saving fetuses is urgent enough to justify this imposition on women. The Thirteenth Amendment argument cannot resolve that question. It can show that, contra Scalia, the imposition raises constitutional questions and places a heavy burden of persuasion on the state. I am inclined to think that the state cannot resolve that burden by simply taking one side of this interminable philosophical debate, at least at the earliest stages of pregnancy when the issue is most doubtful and when most abortions happen.

Whether the Constitution protects abortion is not purely academic, even if today’s Supreme Court cannot be budged on that issue. The movement to abolish slavery had to reckon with the discouraging fact that the Constitution was not on their side. The original Constitution approved of and even protected slavery. It has since been amended. Today’s pro-choice movement needs to understand and say that their opponents are betraying one of the Constitution’s defining aspirations: that America is a free country where our bodies belong to ourselves.