God help me, I thought of John Eastman as a friend.

Today he stands accused in the court of public opinion of being the chief legal architect of Donald Trump’s push to overturn the 2020 election and remain in office. But before that he was a law professor, an activist, and a man with a lot of friends. I’ve been one of them.

By “friend” I mean the friendship one law professor develops with another across ideological lines. Eastman is a devoted member of the far-right caucus of the Federalist Society. I am a devoted progressive and longtime member of the American Constitution Society. We have never agreed on much.

But the ethos of the legal academy bids ideological adversaries to reach across philosophical lines. That supposedly furthers the values we claim to believe in—rational inquiry, open-mindedness, a search for truth. Eastman’s career as an academic was highly political and resolutely far right, but it was also distinguished. As professor and eventually dean of Chapman University School of Law, he was respected by people on both sides of the philosophical divide. Most important to me, of all the Federalists whom I have (for my sins) debated over three decades, John was the only one who ever publicly said, “You know, you raise an interesting point—I am going to have to think about that.”

Today, the strange career of John Eastman raises questions about whether any of those values—civil discourse, careful analysis, mutual respect, the entire small-l liberal intellectual project—have any substance at all, or are just fairy tales that disguise the grim reality that law, and everything else in American politics, is nothing more noble than a knife fight in the dark.

It’s hard to overstate how much trouble John Eastman is in. On January 6, 2021, he spoke to the “Save America” rally on the Washington Ellipse that led to the bloody attack on the Capitol by a mob of Donald Trump’s supporters. Since then, headline after headline has indicated actions taken or threatened against him: Only a few days after he spoke at the January 6 rally, three members of Chapman’s board demanded that he be disciplined. Soon after, the school announced that Eastman would retire and instead concentrate on his visiting professorship in “Conservative Thought and Policy” at the University of Colorado. The Colorado chancellor, meanwhile, said in a statement on January 7 that “[Eastman’s] continued advocacy of conspiracy theories is repugnant, and he will bear the shame for his role in undermining confidence in the rule of law.” Shortly after that, Colorado canceled Eastman’s classes for lack of enrollment and stripped him of his other duties.

When we spoke, Eastman was exactly as I remembered—charming, voluble, seemingly candid, eager to engage in debates over legal theory. In no way did he admit that he had

done anything wrong, or, except in the most general way, fire back against his accusers.

On December 9, 2021, in a deposition taken by the staff of the House Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the United States Capitol, Eastman invoked the Fifth Amendment roughly 100 times. He invoked the Fifth again in an appearance in front of a Georgia grand jury investigating the Trump team’s efforts to pressure Georgia authorities into reversing the result in that state and awarding its electors to Trump.

On March 28, 2022, Judge David O. Carter of the Central District of California wrote in a published opinion that “it is more likely than not that President Trump and Dr. Eastman dishonestly conspired to obstruct the Joint Session of Congress on January 6, 2021”—that is, the official certification of the electoral vote totals that made Joe Biden president. If proved, Carter concluded, Eastman’s actions violated 18 U.S.C. § 371, which forbids conspiring to “defraud the United States,” by “dishonestly” conspiring to file false electoral votes for Trump from states carried by Biden. That statute provides a maximum of five years in prison.

Then, in December 2022, the January 6th Committee, in its final report, issued a “criminal referral” against Eastman by name, proposing a federal indictment for violation of 18 U.S.C. § 1512(c). That statute forbids “corruptly” obstructing, influencing, or impeding “any official proceeding.” Although the committee suggests criminal referrals against Trump, or “President Trump and [unnamed] others,” six times, in only one of these referrals does it name another specific person as a potential defendant: John Eastman.

In January of this year, the California State Bar Trial Counsel announced public proceedings to strip Eastman of his legal credentials. The bar’s complaint alleged six counts of “Moral Turpitude—Misrepresentation” in Eastman’s public statements alleging that the 2020 election was stolen from Trump; one count of “Seeking to Mislead a Court” because, as a lawyer for the Trump campaign, he signed a motion to join the Texas lawsuit asking the Supreme Court to overturn the election; and one count of “Failure to Support the Constitution and Laws of the United States,” because he allegedly tried to pressure then Vice President Mike Pence into rejecting the electors from states Biden won.

Neither the committee’s “referral” nor Carter’s ruling constitutes even a formal charge of criminal wrongdoing. The case in Carter’s court is a civil, not a criminal, proceeding over a subpoena for Eastman’s emails, and a congressional “referral” is nothing more than a suggestion to the Department of Justice. The California Bar has not taken action against Eastman, and might never do so. Criminal charges might be forthcoming—either from the January 6 special counsel Jack Smith or from a state grand jury in Atlanta investigating Trump-campaign pressure on election officials to reverse Biden’s win in Georgia—or, equally likely, they might not.

But criminal jeopardy aside, I’ve become fascinated with what the January 6th Committee’s final report says Eastman did before, during, and after January 6—from the point of view not of a prosecutor, but of a legal scholar. According to the report, after the 2020 election Eastman took up a role as Trump’s consigliere on all matters having to do with “vote fraud” and the Electoral College. He advised Trump that alleged violations of state law in swing states had favored Biden and thus rendered the elections illegitimate, and that the legislatures of those states could respond by “electing” false slates of electors for Trump. He also advised Trump that Pence, who by the terms of the Constitution presides over the electoral vote certification, had the power to reject votes from states in which “unlawful” elections had been held, delay the certification of Biden’s win, and send the issue back to state legislatures, which might decide to pick the electors themselves.

One of the committee’s most important charges is that the latter theory is so thin that Eastman didn’t even believe it himself. How did someone with such a firm professional identity, and such credibility within his chosen legal world, risk it all by making a mockery of the Constitution he claimed to revere?

I reached out to Eastman for an interview, and to my surprise, he accepted gladly. When we spoke on the phone, he was exactly as I remembered—charming, voluble, seemingly candid, eager to engage in debates over legal theory. There was no hint that I was talking to a man brought to bay by some very powerful forces and facing the full shaming power of the Twitterverse; indeed, the conversation was more like a skull session one might have with a colleague in the faculty lounge. In no way did he admit, or seem to feel, that he had done anything wrong, or, except in the most general way, fire back against his accusers.

As a class, law professors are among society’s mildest, most rule-oriented members. We cite, analyze, and apply the law; we criticize it; we suggest improvements. We imagine new situations and suggest new doctrines to respond to them. We draft proposed statutes and regulations. We testify before legislative hearings.

We advocate for our ideas. We push the constitutional envelope and sometimes suggest unprecedented actions. And sometimes we advise private clients, government figures, and other lawyers. We pretty much don’t, as part of a normal career, conspire to violate the law; for constitutional scholars like John Eastman and me, it’s very unusual to be accused of conspiring to overthrow the government.

I can’t help seeing Eastman’s story as a cautionary tale about the peril that awaits all of us when we venture out of the daily world of rules and norms and into the shadow world created by a figure like Trump, whose persistent message is that he is above the law—indeed, that the very idea of “law” is irrelevant to someone like him—and that if we follow him, we can be above the law as well. I also think Eastman’s story tells us something about a serious wrong turn American conservatism took a quarter century ago, and about the dangerous path the Republican Party seeks to guide the nation on.

John Eastman grew up in Nebraska and finished high school in Texas. He graduated from the University of Dallas in 1982 with a bachelor’s degree in politics and economics; then, a decade later, he gained a PhD from Claremont Graduate University, part of the venerable Claremont Colleges consortium in the suburbs of Los Angeles, with a dissertation on “Public Education at the American Founding.” Claremont, then and now, was a center of a school of highly intellectual hard-right conservatism that foregrounded religious history and values as the supposed core of American law and government. Progress on Eastman’s degree was slowed because he took time off to serve as campaign chair for his dissertation adviser, William B. Allen, in a run for the U.S. Senate in 1986. Allen got 0.65 percent of the primary total—fewer Republican votes than the former Black Panther Eldridge Cleaver—but Ronald Reagan’s administration at that time was on the prowl for aggressive Black conservatives, and Allen fit the bill. In 1987, Reagan named Allen a member, and then chair, of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. Eastman became the commission’s press spokesman.

Allen was one of those flamboyant Reagan conservatives who repeatedly went out of their way to outrage those who did not share their far-right philosophy. In 1989, during the height of the AIDS crisis, he gave a high-profile address to an anti-gay Christian group in California. His speech was titled “Blacks, Animals, and Homosexuals: What Is a Minority?” (“Express laws for minority groups,” he warned, “is the beginning of the evil of reducing American blacks to an equality with animals, and then seducing other groups—including homosexuals—to seek the same charitable treatment.”) That same year, Allen thrust himself into a private child custody dispute that he thought had racial overtones by bringing a film crew onto the White Mountain Indian reservation and, without the permission of her guardians, conducting a filmed interview with a 14-year-old Native girl. Suspecting that they were kidnappers, Arizona sheriff’s deputies and reservation police detained the group for five hours before releasing them without charge. Eventually, the incoming George H. W. Bush administration forced Allen’s resignation to prevent Congress from killing the Civil Rights Commission entirely.

I can’t help seeing Eastman’s story as a cautionary tale about the peril that awaits us when we venture into the shadow world of Trump, whose persistent message is that he is above the law—and that if we follow him, we can be above the law as well.

Back in California, Eastman ran for the House in 1990 in a Democratic district, and lost. He worked briefly in real estate, then entered the University of Chicago School of Law. After he got his law degree in 1995, he played a card from the Reagan days—his friendship with Clarence Thomas.

Thomas, like Allen, was an abrasive Black conservative elevated by Reagan and put in charge of an agency (the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission) whose mission he seemed to largely disdain. As Emma Brown and Rosalind Helderman wrote in a detailed Washington Post intellectual biography of Eastman, the staff of the EEOC and the Civil Rights Commission frequently met, and Eastman said later that he and Thomas “had many fond dinners.” But the bond was deeper—it ran through the conservative motherlode that was Claremont. As the Post profile explained,

At the EEOC, Thomas had hired a pair of scholars from the Claremont Institute, at the base of the San Gabriel Mountains outside Los Angeles, where Eastman had been a research associate during graduate school. As Thomas has told the story, John Marini and Ken Masugi engaged him in a sort of tutorial on the American founding, complete with reading assignments and discussions.

Eastman’s new mentor had been named to the Supreme Court in 1991 by George H. W. Bush. Very few law graduates are social friends and intellectual compatriots of Court justices; Thomas was hiring Eastman not only as a clerk but also as a friend and comrade-in-arms. Eastman himself has repeatedly paid tribute to Thomas as an employer and mentor, and as an influence on his own constitutional thinking.

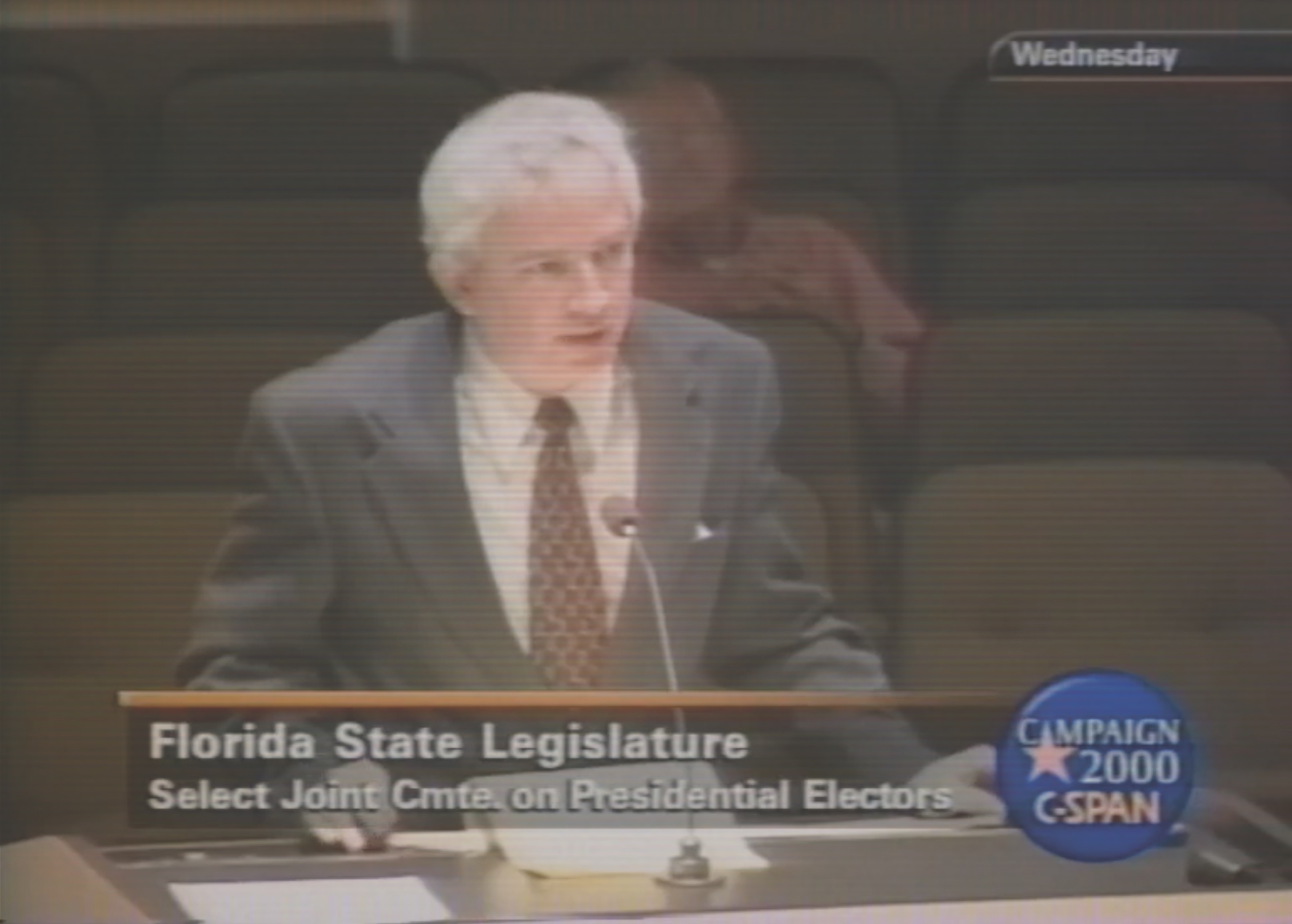

The clerkship, as such high court positions do, opened many doors for Eastman. After it, he moved swiftly into the professoriate, joining Chapman’s Dale E. Fowler School of Law, which was then only four years old but already in an updraft that brought the school first American Bar Association accreditation and then recognition as a major West Coast institution. In only his second year as a professor, Eastman became part of the Republican effort to stop recounts in Florida after the 2000 election and guarantee the White House to George W. Bush.

Here’s Eastman’s own summary of his role in the Florida recount standoff, from a court filing in the case before Carter:

Dr. Eastman was called upon by the Florida legislature to give expert testimony about constitutional issues arising under the elector and electoral college provisions of the Constitution; was retained by the Florida legislature to craft legislation that would protect that State’s electoral votes; and participated as an attorney on behalf of the George W. Bush presidential campaign in post-election litigation in Florida.

In the years after that, Eastman swiftly moved from tenured professor to endowed chair holder, and then became dean of the law school in 2007. But, as his mentor William Allen told the Post, “he was a political animal from his undergraduate days”—and so, when his three-year term as dean expired, he ran for the Republican nomination for attorney general of California. Eastman told me he felt called to make that race because California’s then attorney general, Jerry Brown, had refused to defend Proposition 8, the anti-same-sex marriage initiative passed in 2008. “I was involved in the Proposition 8 campaign as well as the litigation,” he said, “and the attorney general of the state was refusing to defend the initiative adopted by the people of the state.” He lost by a 13 percent margin to Los Angeles County District Attorney Steve Cooley, who in turn narrowly lost the general election to Kamala Harris. “I think I would’ve beaten our now vice president had I won the nomination,” Eastman told me.

Throughout, as director and then chairman of Chapman’s Center for Constitutional Jurisprudence, Eastman maintained a hyperactive career as a conservative legal activist. Under his leadership, his 2014 résumé reveals, the center filed at least 69 amicus briefs in the Supreme Court, weighing in on virtually every high-profile constitutional case that came before the Court—as many as 14 in 2014 alone. He also maintained a busy pro bono practice on behalf of conservative causes like religious freedom and property rights. He was active in his Catholic parish, served as a leader of Boy Scout and Cub Scout troops, and joined the National Executive Committee of the Federalist Society. In 2011, he joined the National Organization for Marriage as board chair. NOM is a well-funded antigay and anti-trans political action group whose greatest success had come in 2008 with the passage of Proposition 8. (The initiative was struck down by the Supreme Court in a 2013 case, Hollingsworth v. Perry, that paved the way for the Court’s 2015 decision in Obergefell that the states must allow same-sex marriage.)

Eastman’s legal scholarship appeared frequently in law reviews, most often, but not invariably, in journals associated with the Federalist Society or the conservative legal movement generally. His op-eds appeared in news outlets from The Sacramento Bee to USA Today.

By his mid-50s, in other words, Eastman would seem to have been sitting pretty. Believe me, readers, being a senior law professor is a very sweet gig: You write what you want and people treat you as if you know a lot.

But as it does for many law professors in the middle of their career, politics was still calling to Eastman. Having triumphed in brutal faculty meetings, profs yearn for real power. Most of them are well aware that two of the past three Democratic presidents—Bill Clinton and Barack Obama—served stints in the legal ivory tower. Hillary Rodham Clinton and Elizabeth Warren both tried to follow their example, as did Harvard’s Lawrence Lessig. Missouri Republican Senator Josh Hawley clearly hopes that in some distant post-Trump era he will be the first Republican ex-professor to do the same. And since William Wolcott Ellsworth of Trinity College became the first law professor to join the U.S. House, in 1829, more than 50 other profs have served in the House or Senate.

Every French soldier, Napoleon is believed to have said, carries a marshal’s baton in his rucksack; many a professorial book bag bulges with gavel and robe, just in case the president calls while the prof is sipping sherry in the senior common room. But the definition of a federal judge, in the old saying, is “a lawyer who knew a senator.” Politics is the way to forge those ties.

And then there’s television, which can be a way of furthering political aspirations and drawing the attention of powerful patrons. Eastman’s TV career picked up steam during the Trump years. He made it onto Fox News only once during Trump’s first two years. But when the Republicans lost control of the House after 2018, his green room footprint deepened as he amassed 36 appearances, defending Trump on everything from the Mueller Report to the first impeachment. (The “I need you to do me a favor” phone call with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, Eastman told Fox’s Laura Ingraham on January 28, 2020, “was a perfectly appropriate thing to do, because there is massive evidence of corruption that we ought to be looking at in this country.”)

As a scholar, Eastman was a generalist—his articles, speeches, and op-eds cover a wide range of topics: the possible limits on Congress’s spending power, the case against same-sex marriage, President George W. Bush’s anti-terrorism measures, the privileges or immunities clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, and state “sovereign immunity” under the Eleventh Amendment. They tend, in fact, to focus on the issues the conservative and religious right legal movements were involved with at a given time, and faithfully to promote the far-right line.

One major preoccupation does show up, however: the proper meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee that “all persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to the jurisdiction thereof are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.” The majority of scholars believe that these words guarantee birthright citizenship to any child (with the exception of the small number who are covered by diplomatic immunity) born on U.S. soil—and in the only Supreme Court decision on the issue, the justices in 1898 found that the guarantee covered the California-born child of legal Chinese immigrants.

Eastman and a few others, however, argue that the words “subject to the jurisdiction” require something additional—perhaps that the parents be lawful permanent residents of the U.S., and thus that children born to undocumented parents (or even those here legally on temporary visas) are born without U.S. citizenship—and perhaps without any citizenship anywhere. This idea has been floating around on the right fringe of constitutional thought for a generation. Eastman’s 2014 CV shows no fewer than 56 speeches, debates, articles, op-eds, or congressional testimonies pushing the restrictive view. One of his constitutional jurisprudence center’s proudest boasts was that one of its amicus briefs espousing this view might have inspired a glancing comment in a dissent by Antonin Scalia that Yaser Hamdi, a Guantánamo detainee who was born in Louisiana to parents on legal temporary visas, was only a “presumed American citizen.” Thus it wasn’t entirely surprising that, after then Senator Kamala Harris, the daughter of immigrants from Jamaica and India, became Joe Biden’s 2020 running mate, Eastman wrote an opinion column in August 2020 for Newsweek suggesting that because her parents were “merely temporary visitors” to the U.S. when she was born, she was not only ineligible to be vice president but also not even a legitimate U.S. senator.

Newsweek later apologized for publishing this extreme position: “We entirely failed to anticipate the ways in which the essay would be interpreted, distorted and weaponized … All of us at Newsweek are horrified that this op-ed gave rise to a wave of vile Birtherism directed at Senator Harris.” Eastman defends the piece to this day. He points out that he didn’t invent the theory as a slap at Harris; he’s been pushing it since at least 2001.

Every French soldier, Napoleon is believed to have said, carries a marshal’s baton in his rucksack; many a professorial book bag

bulges with gavel and robe, just in case the president calls while the prof is sipping sherry in the senior common room.

But it’s certainly possible that Eastman’s creation of a new birther-style meme found favor with America’s foremost birther, Donald Trump. Trump had burst into national politics with his single-minded embrace of the claim that Barack Obama was actually born in Kenya; during the 2016 campaign he loudly proclaimed that children of the undocumented should not be citizens—and, in fact, not just of the undocumented. During the Republican primary campaign he claimed first that Senator Ted Cruz (born in Canada to an American mother) was ineligible to run, then geared up to challenge Senator Marco Rubio (born in the United States to legal immigrants from Cuba) as well. Eastman disclaimed knowledge of who first put his name before Trump. “I didn’t have any dealings with him” until after the election, he told me.

At any rate, two weeks after the Newsweek op-ed appeared, the Trump lawyer Cleta Mitchell brought Eastman aboard the campaign’s volunteer “Election Integrity Working Group,” which was preparing to contest the expected theft of an election still two months away. By the next month, the nearness to Trump’s orbit seems to have begun working its sinister magic. Erwin Chemerinsky, a prominent progressive who is currently the dean of the University of California Berkeley School of Law and a former dean of the University of California at Irvine’s law school, recalled that he and Eastman had been debate partners for 16 years on the conservative professor Hugh Hewitt’s high-profile radio show. Chemerinsky recalled their association fondly. “I always felt that he was very conservative,” he told me, but “we were arguing the issues” rather than trading barbs. That October, however, Chemerinsky made a joint radio appearance with Eastman on a different program and found him changed. “John was very different than he ever was before,” Chemerinsky said. “He was nasty, he was talking over me. It was almost like debating Trump.”

On December 5, 2020, Eastman signed a formal document assuming a role as counsel for Trump and the Trump campaign in their election challenges. This wasn’t cable news provocation anymore. Now he was in the World Series, taking the pitcher’s mound for a team that was behind by three runs in the top of the ninth inning. He was, in other words, about to get in seriously over his head.

In his account of events, Eastman was brought in because the campaign was anticipating a challenge to the election results by Texas and other red states. Texas filed that lawsuit three days later, and because this was an “original action” by states against other states, it went directly to the Supreme Court. The next day, Eastman was the sole counsel signing a motion by Trump to intervene in that case. That motion made two claims. The first was that the vote totals were suspicious:

President Trump prevailed on nearly every historical indicia of success in presidential elections. For example, he won both Florida and Ohio; no candidate in history—Republican or Democrat—has ever lost the election after winning both States … Republican candidates for the U.S. Senate and U.S. House, down to Republican candidates [at] the state and local level, all out-performed expectations and won in much larger numbers than predicted, yet the candidate for president at the top of the ticket who provided those coattails did not himself get over his finish line in first place.

In other words, Trump should have won, and therefore there must have been some fraud when he did not win. Numerous statistical analyses of voting data right after the election, and later looks at actual voter files, rebutted this conjecture. They showed that Trump lost even though many other GOP candidates won, largely because a sufficient number of Republican voters simply chose to vote straight tickets except for Trump—voting instead for Biden, for third-party candidates, or for nobody. Considering that polls showed that Trump was an unpopular nominee, this result seems unsurprising.

The second, separate claim was that courts and officials in the swing states had applied the state’s election statutes in ways that the legislature might not have approved. According to Eastman’s filing, “To the extent these drastic and fraud-inducing changes in state election law were done without the consent of the state legislature, the federal constitution was violated.”

This brings us to the core of the case against Eastman, as laid out in the January 6th Committee report, best expressed in the two famous “coup” memos he wrote in late 2020 and early 2021 outlining a scheme by which Vice President Mike Pence could reject electoral votes from states that the Trump campaign believed Trump should have carried and thus somehow must have carried. As a legal scholar, I have spent considerable time with those memos; they are fascinating documents, and they reveal the Trump theory to have been so flimsy that it is difficult to believe that any serious person took them seriously.

It’s important to note what the Eastman theory does not say. Although in public (as in the “Save America” speech) Eastman repeated a number of the wildest charges that fraudulent voting machines or fake ballots switched the result in these states, his memos don’t say that; indeed, the second, six-page memo says, “Quite apart from outright fraud (both traditional ballot stuffing, and electronic manipulation of voting tabulation machines), important state election laws were altered or dispensed with altogether in key swing states and/or cities and counties.”

Outside a few law review articles, there’s no case law to support the idea that the vice president can delay the electoral count. So, in essence, Eastman’s argument is that both the states and the federal government have been running unconstitutional elections since 1888.

“Quite apart” does a lot of work here. Read with a professorial eye, the claim is not a fraudulent result exactly—it’s that the states did not follow their own laws to Trump’s satisfaction. It stops just short of claiming that enough votes were somehow switched to change the result. Despite his press statements, I can’t find anywhere in the record where Eastman formally alleged that these actions by state officials switched enough votes to change the result. In our interview, he said, “I never said that there wasn’t enough fraud to have affected the election, because the amount of fraud is very hard to prove after the fact, after the envelopes were separated from the ballots.”

In fact, Eastman told me, he does believe that the election was stolen, in part because of the $400 million grant given by Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg to a pair of nonprofits funding improvements to local election boards. “You look at where that money went, and you look at the turnout bump up there—that seems pretty clear to me.” The second piece of evidence he cited was supposed anomalies in the vote totals in 18 “bellwether” counties around the country—including one in Idaho, a state Trump carried by 30 points. When I asked why any Democrat would bother to rig votes in this reddest of red states, he explained that “there’s a major effort to get rid of the Electoral College, and the way they do that is focus on the national popular vote … and so there was incentive to pump up numbers elsewhere too.”

I will simply say that the validity of this inference is not entirely clear to me.

But the other part of the theory didn’t depend on fraud. The second problem was, apparently, simply that the state elections were “unlawful.” The core of the allegation, both in the “coup” memos and in the Supreme Court motion, was not that ballot boxes were stuffed with votes by dead or nonexistent voters or that lawful ballots weren’t counted; it was that the state courts and state election boards made decisions about details of the voting—hours in which polling places were open, for example, the number and location of drop boxes, or the formalities necessary for submitting a mail vote—that differed in some way from the way the Trump campaign read the wording of the statutes. In the Eastman theory, only the state legislatures are empowered to make any decisions about voting, regardless of what state constitutions say or what authority state courts and officials have under those state statutes. “My view … is that when the election is conducted not according to the manner that it was directed by the legislature, it’s an invalid election,” he told me.

In other words, it didn’t matter whether Trump had obtained more votes than Biden in that swing state; the mere presence of these “unlawful” votes rendered the entire election “unlawful” and thus voidable by the state legislature. Eastman stands by this theory today. He quotes dictum from some court decisions and scholarly speculation; but the theory is a rickety construct in which several of the major supporting girders are either weak or nonexistent.

It is the equivalent of a claim that the Kansas City Chiefs didn’t actually win Super Bowl LVII because a review of video after the game showed that one of their players lined up a few inches offsides during the crucial field goal, and that the Philadelphia Eagles will be world champions if they show up in the dead of night and send a running back with the ball across the goal line unopposed. Or maybe it’s even worse than that—because at least there already is a rule against being offsides.

On January 11, 2021, Eastman sent an email to Rudy Giuliani asking to be included on the “pardon list.” At some point between October 17 and January 6, Eastman crossed all kinds of lines, and he apparently knew he had crossed them.

The claim that only state legislatures can interpret or apply state law governing presidential elections is not the law as it exists today. It’s a very controversial idea, one that has been ridiculed by the majority of scholars who study the Constitution’s electoral provisions. There’s certainly no case that says that, exactly—only some snippets of old cases that Eastman and other contemporary conservatives have fashioned into the “independent state legislature” doctrine. That far-right claim is now pending before the newly conservative Supreme Court—but today, as in 2020, the doctrine has not been recognized as a constitutional rule by any court. And even if the independent legislature theory is eventually adopted by a conservative court, there’s also no precedent providing that the mere fact that a state official deviated from a legislative rule invalidates an accurately counted election.

The final aspect of Eastman’s theory was that, when Congress met on January 6 to count the electoral votes and declare the winner, Pence would have the unilateral power to reject the slates of electors chosen in the actual swing state elections, and “remand” the vote to the state legislatures for some kind of legislatively contrived “recount”—or a simple legislative resolution designating the Trump electors as the “official” ones.

Never mind what I think of this—let’s hear what one prominent constitutional scholar wrote about Eastman’s claim as recently as October 2020:

I don’t agree with this … The Twelfth Amendment only says that the President of the Senate opens the ballots in the joint session and then, in the passive voice, that the votes shall then be counted. [The Electoral Count Act] says merely that he is the presiding officer, and then it spells out specific procedures, presumptions, and default rules for which slates will be counted. Nowhere does it suggest that the President of the Senate gets to make the determination on his own.

The scholar who flatly refuted the John Eastman theory was, in fact, John Eastman. The January 6th Committee report documents correspondence in October 2020 between Eastman and a Trump supporter named Bruce Colbert. The refutation I quoted above is from that correspondence—in which Eastman responded to Colbert’s suggestion that Pence had that power. I asked Eastman about the charge that he gave phony advice to his clients, and he responded that when he wrote the memo to Colbert, he was still “treating the Electoral Count Act”—the federal statute that provides congressional procedures for the electoral certification—“as controlling, because I’d never had the need to do the deep dive in assessing whether in fact there were unconstitutional aspects of the Electoral Account Act.” By December, he said, he’d done the research and he had “come to the conclusion that [the act is] not constitutionally valid.”

In our interview, Eastman was very careful to state that though his “coup” memos raised the possibility that Pence could simply reject enough Biden electors to make Trump the winner on the spot, he himself did not and does not endorse that idea. He does, however, stand by the idea that Pence could have declared a pause in the certification process so the state legislatures, which were beginning to assemble for their yearly sessions, could, in his words, “delay at the request of the more than a hundred state legislators who had written [to Eastman] and said, ‘Our elections were conducted illegally and opened the door for enough fraud to have affected the outcome. We want to look at this now that we’re back in session. Give us a week or 10 days.’ ”

Having carved out extreme positions, Eastman now found himself in the orbit of a president who expected him to make good on them—and who could, if reelected, not only make Eastman’s far-right policy wishes come true but also reward Eastman himself in very concrete ways.

It has to be said that the “Pence delays” scenario has even less law backing it than the “Pence rejects electors” scenario does. The Electoral Count Act specifies that the votes shall be counted on January 6. Nowhere does it give the vice president the authority to delay the count. Eastman deals with that uncomfortable fact by asserting in both “coup memos” that the act itself is “likely unconstitutional.” Outside a few law review articles, there’s no case law to support that idea. So, in essence, Eastman’s argument is that both the states and the federal government have been running unconstitutional elections since 1888.

Here’s the final and in some ways most damning fact about Eastman’s conduct before January 6: He advised Pence to do things that on their face seemed clearly illegal—but to try to do them in a way that would prevent any court from stepping in. In his first memo discussing a “vice president blocks electors” scenario, he wrote, “The main thing here is that Pence should do this without asking for permission—either from a vote of the joint session or from the Court.” This strategy is in line with what Trump proposed to two officials of the U.S. Justice Department on December 27 when they protested that the department had not found evidence of fraud to support the president’s claims: “Just say the election was corrupt and leave the rest to me and the Republican congressmen.”

In other words, it looks as if Trump and Eastman were looking for an excuse to block or paralyze the certification and allow Trump to proclaim that the election was, in some way, a failure that could be rectified by Republican legislatures or Republican members of the House. “Unlawful” votes that were not enough to change the result? Well, they were still “unlawful” so we get a mulligan. Outlandish vice presidential power theory? Well, we can get away with it as long as no court has time to step in.

For lawyers, this is a bit like advising a client, “If you want to grab merchandise from the shelves without paying, all you need to do is make sure there are no security guards between you and the store entrance.” Considering that in the Eastman case the advice deals with the heart of the U.S. Constitution, the Pence scenario seems deeply questionable for a scholar to concoct, ethically shaky for a lawyer to recommend, and legally dangerous for a citizen to act on.

It is chilling to think that if even one of the guardrails had failed—if even one state legislature had met in special session, for example, and caved to Trump and sent an “official” slate of fake electors, or declared their state’s popular vote invalid, or if Pence had agreed to suggest that there was doubt about the swing state vote totals or had let himself be evacuated from the Capitol and not permitted to return in time—it could very easily have worked.

But it failed, and on January 11, 2021, Eastman sent an email to Rudy Giuliani asking to be included on the “pardon list.” At some point between October 17 and January 6, Eastman crossed all kinds of lines, and he apparently knew he had crossed them. Startlingly, he has not even tried to scramble back. Having offered the bogus theory that the legislatures could block Biden’s election before January 6, he has suggested to some legislators that their state legislatures, even now, halfway through Biden’s term, could somehow “decertify” their electors and perhaps even remove Biden from office. I asked him about this, and he eagerly tackled the theory. He granted that the Constitution provides only two ways to remove a president: impeachment or removal under the Twenty-fifth Amendment. But, he said, the Constitution doesn’t say there can’t be a third way. If a court finds that a presidential election was fraudulent, he suggested, “you fall back on basic common law principle” in which “proven fraud … vitiates [voids] the act taken”—presumably by evicting Biden from the White House. This theory leaves behind the entire world of precedent and the Constitution, and boldly goes where no lawyer, to my knowledge, has ever gone before.

Eastman hastened to add that he had advised the legislators that as a matter of politics, “it’s not gonna happen.”

Reasonable people can disagree on some points of the ability of state legislatures to control the selection of electors during the time before a president is chosen. But once we get into the idea that partisan legislators can even try to jam the defeated candidate into office at midterm, we have booked business-class reservations on the last train to Crazy Town.

How did he get here? Perhaps, after all the pro–Trump administration speeches and Fox News spots pushing far-right talking points, Eastman in the fall of 2020 was now the dog who had caught the car—or Chauncey Gardiner in Jerzy Kosinski’s Being There, the random bystander who blunders into a position of influence because listeners mistake his musings for wisdom. At any rate, having carved out extreme positions, Eastman now found himself in the orbit of a president who expected him to make good on them—and who could, if reelected, not only make Eastman’s far-right policy wishes come true but also reward Eastman himself in very concrete ways. He might have had an occasional thought about his own possible role in a Trump second term—as an official in the White House, the Justice Department, or even … the Supreme Court?

Besides this, the prospect of jimmying the Electoral College offered Eastman a chance to pursue a legal white whale that he had been chasing for at least 20 years—the role of state legislatures in the Electoral College. And that takes us back to the Florida 2000 electoral standoff.

Immediately after the 2000 election produced an agonizingly close result in Florida, Republican staff and legislators in Tallahassee began discussing the possibility of having the Republican-dominated legislature step in, proclaim a winner, and select a set of Bush electors. When the state senate convened a hearing, two eminent law professors—Bruce Ackerman of Yale and David Strauss of the University of Chicago—testified that the legislature’s constitutional power to “direct” the “manner” by which electors are to be selected did not include the power to revoke an election that had already been conducted. The committee, which wanted to do exactly that, quickly sought an expert who could explain the Electoral Count Act. Eastman tells this part of the story with Homeric gusto: “What happened is they had a four-hour hearing”—on the legislature’s supposed power to designate its own electors—“and nobody had any idea what they were talking about.” Committee staffers realized that they needed an expert on the proper procedures, and there was none available. “Nobody,” Eastman said, “had looked at the electoral count or the Twelfth Amendment since 1887.” Someone suggested the name of a junior professor at Chapman Law School: John Eastman.

According to Eastman, a Republican staffer called him and asked whether he could opine on the issue. “I said, ‘I don’t know anything about it, but I do know a lot about the structural Constitution. When do you need me to testify?’ And he said, ‘Tomorrow.’ And I said, ‘Well, get me a first-class ticket.’ ” He and half a dozen Chapman law students spent the next 12 hours reading microfiche records of congressional debates. “They pulled me together about four binders of microfiche stuff and I read it on the plane and I go testify the next morning,” he told me.

Eastman, who had been a professor for less than two years, was suddenly at the center of history—and empowered to talk back to superstar profs like Ackerman and Strauss. The plan of the legislature proclaiming victory for Bush electors did not come to fruition, but only because the Supreme Court stepped in and halted the state’s recount process.

Nonetheless, the experience seems to have left an indelible impression on Eastman. By 2022, his version of the “independent legislature” theory had become such a rococo construct that it’s not hard to imagine that it had been growing in his mind since the near rendezvous with history in 2000. By 2020, the entire electoral process—as set out in both the Constitution and the Electoral Count Act—had become, in Eastman’s analysis at least, nothing more than a collection of ambiguities, unresolved paradoxes, and open constitutional questions.

Eastman’s advice to Trump and Pence seems to flow directly out of his experience in Florida. But that advice went considerably beyond what the Florida legislature was prepared to do. In fact a lot of Eastman’s 2020 plan depended on essentially defying parts of the Electoral Count Act as unconstitutional, and allowing the vice president to act in an unprecedented way in the electoral count—without any serious court precedent to back this up.

Eastman, however, says there is “scholarship” to back up both contentions, and it is an “open question.” He frequently cites a snippet from an 1892 Supreme Court case, McPherson v. Blacker, in which the Court dismissed a challenge to a system of popular vote by districts rather than statewide. Eastman relies on this line: “There is no doubt of the right of the legislature to resume the power [to direct the manner of selecting electors] at any time.”

Eastman claims the line means that the legislature could provide for a popular election, then revoke it after Election Day because it suspects skullduggery at the polls. That, however, wasn’t the issue in McPherson—nor is that part of the Court’s actual reasoning in the case. In fact, it is a quotation, simply noted by the Court, from a Senate report for a bill considered in 1874—a bill that did not pass.

Eastman’s other argument is that an “invalid” election is void—and thus that the state has, in the language of the Electoral Count Act, “failed to make a choice,” meaning that the legislature can make a new choice. The problem with this argument is summed up in the old anecdote about Abraham Lincoln, who asked an aide, “How many legs does a cow have if you call a tail a leg?” When the aide answered, “Five,” Lincoln responded, “No, four—because calling a tail a leg doesn’t make it a leg.” The people of the 2020 swing states did not “fail” to make a choice; they made one that the Trump campaign did not like and wanted to revoke even if accurate.

To me, the reasoning during those preelection weeks in 2020—building castles of inference on snippets of tortured text and scraps of statutes—bears the firm imprint of Eastman’s friend and mentor Clarence Thomas. Almost since his earliest days on the Supreme Court, Thomas has specialized in separate opinions (separate, because no other justices, liberal or conservative, would join them) in dozens of cases contending that the Court should simply sweep aside decades of established precedent and impose his individual view on the nation. For most of Thomas’s three decades on the Court, his colleagues have simply ignored these opinions. It may be that, after the Trump administration’s annexation of the Court, their hour has come round at last; but neither his views, nor his method of reasoning, is part of the law in 2023.

Beyond that, I find myself wondering whether the 2020 imbroglio was the downstream result of Florida 2000. The Florida battle left an indelible impression on the entire Republican Party and the conservative movement. Though history has so far spoken in restrained terms about what happened there, the brutal fact is that one American political party hijacked the electoral process, prevented an honest count of votes, assumed state power, and plunged the nation into a destructive war from which it has not yet fully recovered. It’s possible that, as some historians claim, Bush would have won an honest recount in Florida, but it is undeniable that he was willing to accept the state’s electoral votes without one.

Florida 2000 marks a turning point—perhaps the turning point—in the history of American democracy. The Republican Party got away with muscling its way into power, and the effect of that success is powerful even today. Consider the following:

On November 22, 2000, one week before Eastman’s testimony to the legislators in Tallahassee, a mob of Republican staffers, under the leadership of party officials and activists, swarmed the room where Miami-Dade election officials were attempting to complete a recount so the state’s vote could be certified by December 12, the federal statutory “safe harbor” deadline. Party cadres, under the direction of a member of the U.S. House, swarmed the room, shouting, “Shut it down!” After a melee in which several people were trampled, punched, or kicked, the mob managed to intimidate the election board into suspending the count.

A generation of Republican legal activists, from future Solicitor General Theodore Olson to future Senator Ted Cruz to future Supreme Court Justices John Roberts and Brett Kavanaugh, went to Florida and fought in the trenches in the battle shaped by that lawless action—a battle that paid little heed to legality and much attention to brute political force.

As a recount ordered by the Florida Supreme Court proceeded, Eastman and members of the Republican majority in the state legislature prepared to set aside the results of that count and designate a slate of electors who would guarantee Bush’s election, regardless of the result of any order from the Florida Supreme Court.

Finally, the U.S. Supreme Court stepped in and simply ordered the recount halted on the flimsy ground that recounting the vote somehow violated George W. Bush’s rights under the equal protection clause—and that the Florida Supreme Court, the supreme authority on Florida law, had read that law wrong. This decision made rubbish of all the pieties that the conservative majority had spouted about federalism; indeed, it hardly pretended to be law. The only direct defense of it anyone on the Court has ever offered was Justice Scalia’s rhetorical upraised middle finger: “Oh, get over it!”

Has either the Supreme Court or the Republican Party ever really gotten “over it”? Florida 2000 was in effect the Big Bang for the authoritarian streak of the GOP. It hardly seems like a coincidence that Florida in 2023 has advanced much farther down the road to outright, explicit fascism than any other state. Governor Ron DeSantis and those around him had a detailed lesson in how a party can step over the lines of decency and law—and reap rich rewards for doing so.

The conservative majority on the Court in 2000 won what they wanted: continued Republican dominance. Both John Roberts and Samuel Alito know they would not be on the Court if a full recount had swung the election to Gore. And the conservative majority made the delightful discovery that, after this most consequential and lawless power grab, the Court suffered only the most minor impairment to its prestige.

The riot in November 2000 was at least in part organized by the Republican operative Roger Stone—the same Roger Stone who, convicted of witness tampering and then pardoned by Donald Trump, strolled, jaunty in Homburg hat and supervillain shades and surrounded by a bodyguard of far-right paramilitary thugs, into the January 6 “Stop the Steal” rally that preceded the attack on the Capitol. It’s not hard to imagine that Stone and other veterans of the Miami-Dade demonstration (and, for that matter, Trump himself) wanted to repeat that performance by shutting down another vote count, this one not in a local election but in a proceeding at the heart of the Constitution, the vote of the Electoral College.

John Eastman was there in 2000, and again in 2021, spouting constitutional theories even flimsier than the recounting-is-unfair-to-Bush notion, and bidding doubters not to worry about courts or law.

The Trump years served as the modern conservative movement’s version of the myth told in the Christian gospels, in which Satan carries Jesus onto a high mountain, below which are spread all the kingdoms of the world, and says, “All these things will I give thee, if thou wilt fall down and worship me.”

In the gospel myth, Christ passes the test. But how many of us mortals would? Some Republicans seem to have made it—Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger, Arizona House Speaker Rusty Bowers—but many did not. Consider William Barr, formerly a respected figure who reduced himself to vile toadyism and outright deceit to defend Trump from legal danger; consider Lindsey Graham, formerly, like his late friend John McCain, a figure with a reputation for independence who now crawls in Trump’s wake croaking “my precious”; consider Rudy Giuliani, once presidential timber but last seen by history as Pagliacci, hair dye dripping as he stumbled through a parody of legal argument on behalf of Trump.

No one goes into politics because they glory in seeing neutral processes play out and really don’t care who wins the game as long as it is fair. All of us—from minor players to protagonists, from politicians to professors—have devout wishes for what we believe the country can become; many of us see those who oppose us not as colleagues or friends but as enemies. Today’s right has convinced itself that the tepid progressivism on offer from the Democratic Party is actually aimed at, and capable of, leading us all to a godless, murderous Gehenna like Pol Pot’s Cambodia. Michael Anton, a colleague of Eastman’s at the Claremont Institute, wrote a famous article in 2016 calling that year’s vote the “Flight 93 election,” because the election of Hillary Clinton would be so disastrous that conservatives, like the heroic passengers who crashed one of the hijacked planes on 9/11 rather than allow it to be flown into a target, should wreck the entire political system if necessary to block her from the White House. For many conservatives, hating and thwarting liberals has become the sole imperative for the salvation of the nation and the souls within it.

To people with this level of hatred, the tempter whispers that their deepest wishes can come true if they will just give up this nonsense about “legality,” “fairness,” and “democracy.” You were never really serious about that, were you? he murmurs. Step over this line, and you will sit at the right hand of power and the evildoers will depart into everlasting fire.

Donald Trump had the unique ability to offer these conservatives their heart’s desire. The serpent tempted them, and they fell.

Is that what happened to my friend John Eastman? I can’t say; I am no examiner of hearts. But if it is, God help him.

And God help us all.