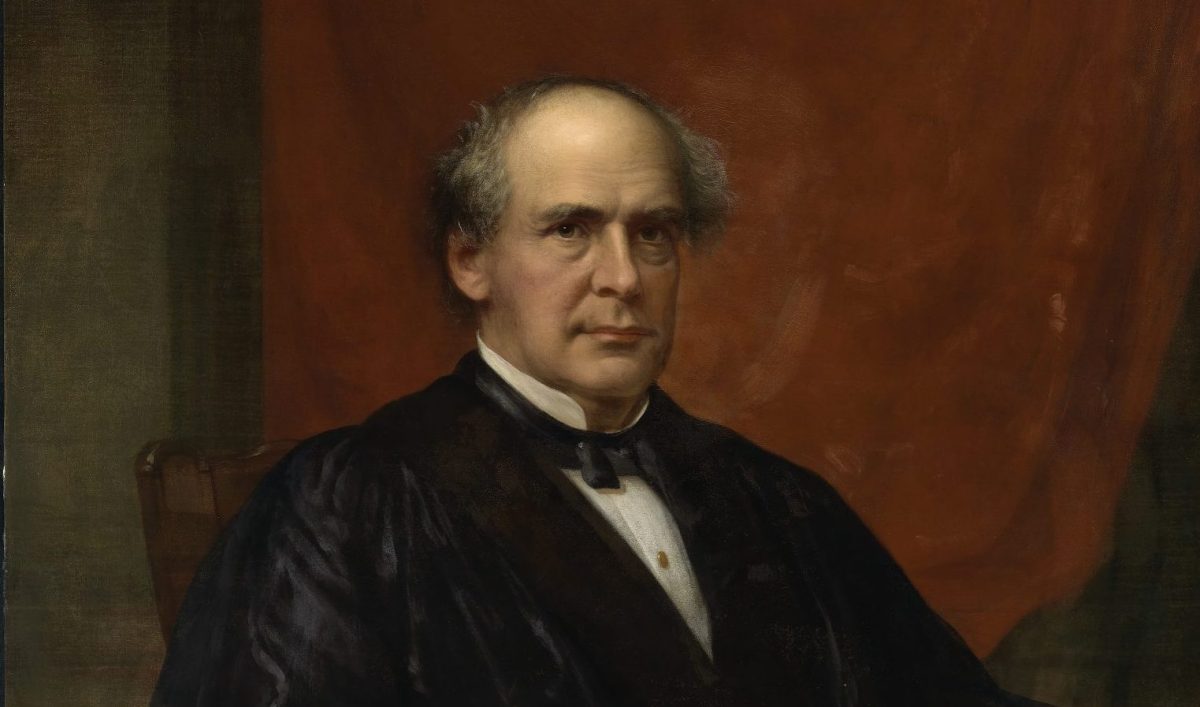

Nearly 200 years ago, several intrepid lawyers began a quixotic campaign to have courts declare the Fugitive Slave Acts of 1791 and 1850 unconstitutional. The attorneys were not successful as a matter of constitutional law. Salmon Chase, the abolitionist who later became Abraham Lincoln’s Treasury Secretary and Chief Justice of the United States, and his associates gained some victories in state judiciaries but never in federal courts.

When the losses piled up, contemporaries of Chase surely declared, I told you so. Federal justices in antebellum America were not going to join an antislavery crusade. Had he been around then, Harvard Law Professor Lawrence Lessig might have regarded Chase’s effort as the same “disaster” as he presently claims of the litigation campaign to disqualify Donald Trump. Time travel permitting, Yale Law Professor Samuel Moyn might have asked, as he asked of the litigation campaign to disqualify Donald Trump, “whether the entire project of pursuing our best political future through the constitutional politics of asking high court judges to take our side—as opposed to democratic political struggle to achieve our goals—is either credible or practical.”

The abolitionist project of the 18th century teaches 21st-century lessons about the litigation efforts to disqualify Donald Trump, but they are not the lessons offered by Lessig and Moyn, who chided court-centered efforts to keep Trump off the ballot. Litigation may be successful in the court of public opinion, even when lawyers fail in court. Writing a requiem for any litigation campaign, as Lessig and Moyn did, immediately after the Supreme Court’s decision earlier this winter ordering Trump to remain on the Colorado ballot was premature.

Abolitionists regarded their litigation campaign as political as well as legal. Some abolitionists litigated. Some organized antislavery political parties. Chase did both. The Ohio politician and his allies were fully expected to lose in federal courts; however, optimistic prominent antislavery advocates waxed in public. Their goal was to contribute to the democratic political struggle to restrict and abolish slavery. Theirs was not an effort to replace constitutional politics with constitutional law. Litigation kept slavery in the public consciousness and forced Northerners to confront the plight of the enslaved on a regular basis. Federal judicial decisions exposed the hypocrisy behind Southern state rights claims. While slaveholders and their northern allies saluted the principle that each state determined the status of persons in its jurisdiction, that rule did not apply when slavecatchers demanded that free states return alleged fugitives without a hearing. Antislavery advocates in politics would reap the benefits of antislavery litigants. When slavery was finally abolished, Chase was the sixth Chief Justice of the United States.

More than 150 years after Congress repealed the Fugitive Slave Acts and sent the Thirteenth Amendment to the states, Lessig emulated American abolitionists by challenging a state law that compelled presidential electors to vote for the candidate they had pledged to support. Unfortunately, he was not successful, and no Supreme Court justices adopted his position.

Nevertheless, Lessig’s litigation campaign was neither a disaster nor politically naïve for being blocked by the courts. Opponents of the Electoral College did not abandon other avenues for repeal while waiting for an authoritative judicial decision. The litigation brought public attention to the Electoral College’s weaknesses and exposed judicial hypocrisy on originalism. The campaign against the Electoral College is stronger today than in 2020 and certainly no weaker, partly because of Lessig’s admirable litigation effort.

University of Washington Political Scientist Michael McCann’s Rights at Work: Pay Equity Reform and the Politics of Legal Mobilization details why, contrary to football coach Vince Lombardi’s famous adage, winning in court is not everything (or the only thing) in litigation. Advocates often overestimate their chances of winning, but litigation frequently transcends unfavorable judicial decisions. Litigation raises consciousness, keeps issues before the public, and creates allies, even if those allies do not wear robes. Litigation forces some hostile officials to take positions that may have adverse political consequences for them in the future.

The history of the legal campaigns to declare fugitive slave laws unconstitutional, enable presidential electors to vote their conscience and provide women with the same pay as men who perform analogous jobs suggests that the requirements for the legal campaign to disqualify Donald Trump may be premature. That litigation campaign garnered one less vote on the Supreme Court than the litigation campaign against the fugitive slave acts in the twenty-five years before the Civil War—and the same number of votes as the campaign for conscientious presidential electors. Some participants made overoptimistic claims in public and may have even believed them privately. (I stand by my comment that the campaign had a “puncher’s chance.”) Nevertheless, in other dimensions, the litigation campaign may have been a successful endeavor in constitutional politics even though constitutional law failed.

The lawyers who asked courts to disqualify Trump kept the issue of Trump’s role in the January 6, 2021, insurrection in the public eye during a crucial period in the presidential campaign. An argument that began as speculation by several law professors convinced numerous citizens, prominent and otherwise, that Trump was not constitutionally qualified to be president. Three members of the Supreme Court declared Trump to be an “oathbreaking insurrectionist,” a phrase that will no doubt be frequently repeated on the campaign trail. Many persons who fought disqualification largely conceded Trump was an oathbreaking insurrectionist while pointing to constitutional technicalities that justified in their minds overturning the decision of the Colorado Supreme Court. Their arguments against disqualification made for successful constitutional law—but wielded properly by Trump’s opponents—may come back to haunt the former president.

The legal campaign to prevent Trump from regaining the presidency has not diminished the political campaign to prevent Donald Trump from regaining the presidency. The lawsuits were brought by two public interest groups that hardly anyone had heard of before the litigation. Five to seven law professors spent more time than they otherwise might have writing essays and short blog posts defending disqualification. The rest of the anti-Trump world continued fighting. While we waited for the Court’s decision, no one stopped raising money for political campaigns against Trump, organizing coalitions to fight Trump, or persuading their neighbors to mobilize against him. Disqualification was merely one front in the struggle to preserve constitutional democracy from MAGA barbarians.

In deciding for Trump, the Supreme Court acquired no additional political capital that might be employed against progressive rights and institutions. Instead, the opinion in Trump v. Anderson discredits conservative claims that the Court is making decisions on the neutral basis of text and history. The text of Section Three does not support the judicial distinction between state efforts to disqualify candidates for state office and candidates for federal office. No Section Three author made such a claim during the debates over the Fourteenth Amendment. Chief Justice John Roberts & Company love state regulation of federal elections except when they do not. There is no evidence that undecided voters are moving to Trump due to the disqualification litigation or that Trump’s claimed vindication has moved anyone outside the MAGA base. Rather, as the campaign continued, an increasing number of persons concluded that Donald Trump is not qualified to hold the presidency. Several polls, here and here, indicated a greater percentage of the public favored disqualification than voted for Donald Trump.

The legacy of the litigation campaign to disqualify Trump is yet to be determined. Lessig, Moyn, and others may correctly point to differences between the litigation campaign to disqualify Trump and other litigation campaigns that had a beneficent impact on constitutional politics.

The crucial point is that the success of the litigation campaign for disqualification depends on the future and not on the recent Supreme Court’s decision. Perhaps Trump will convince crucial voters that he was vindicated by the justices. Another possibility is that crucial voters will realize that Trump responded to claims that he was an “oathbreaking insurrectionist” with procedural technicalities. By keeping January 6 in the public eye, the campaign to disqualify Trump may win in constitutional politics what was not gained in constitutional law.