When Luodan Li told his parents he wanted to go to college in the United States, his mother teased him, saying he was just running away from the gaokao, China’s high-stakes, famously anxiety-inducing national entrance exam for domestic universities.

Luodan, who is from Shanghai, relented and did well enough on his exams to be placed at East China Normal University, a nationally renowned research institution in his hometown. But Luodan was disappointed that “all the emphasis was just on getting in,” and it wasn’t long before his parents changed their mind. “They saw all their friends’ children were going to America,” Luodan said, “and they thought that I was falling behind.”

Now that he had his chance, Luodan realized that he didn’t know where to start with the complex process of applying to an American college, so he contacted an agency in Shanghai, one of thousands across the country that have made an industry of helping wealthy Chinese students apply to American colleges. For anywhere from $5,000 to $15,000, the agency takes care of every detail of the application process, from assisting students in writing their essays to providing letters of recommendation. The agency gave Luodan a list of schools based on rankings from the U.S. News & World Report and told him to choose six. Luodan’s parents paid the agency, half up front and half a few months later when he got his acceptance letter from Purdue University.

In the fall of 2010, when Luodan got to Purdue, in West Lafayette, Indiana, he was part of an enormous wave of new Chinese undergraduates arriving on campus. In the past five years, the number of Chinese undergrads at Purdue has grown from just 127 to 2,755, mirroring a similar trend at colleges and universities across the U.S.

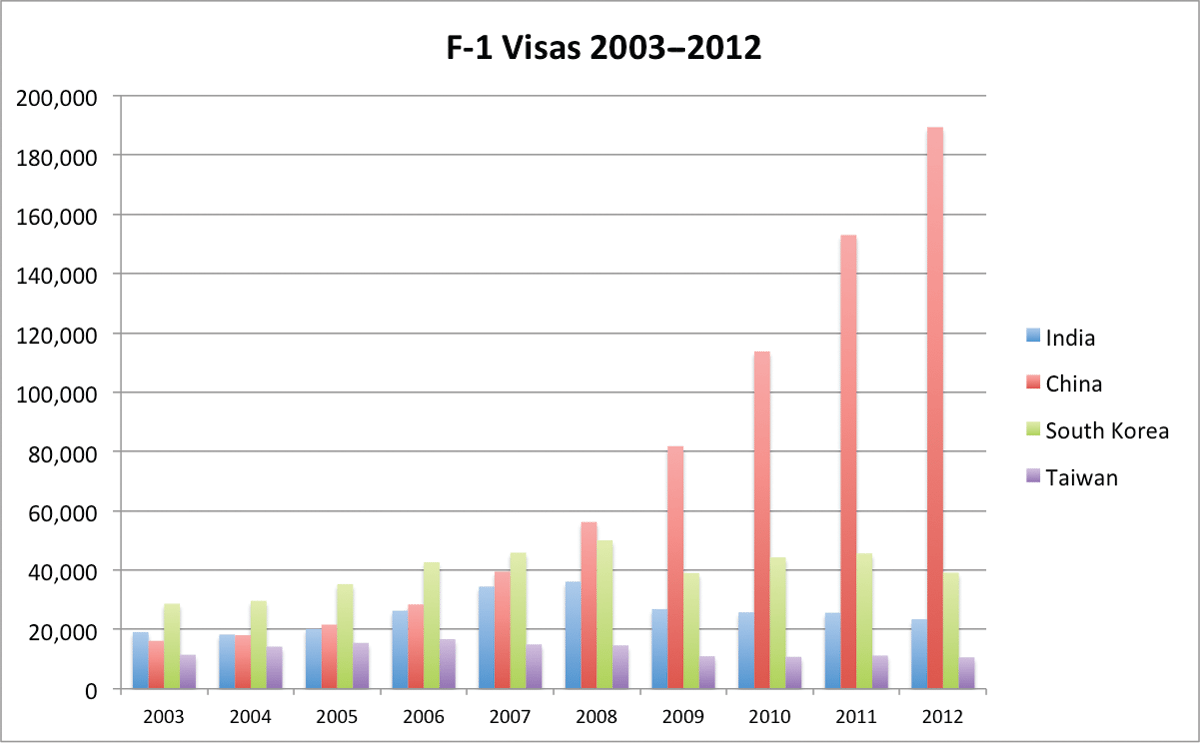

Since 2006, the total number of international students at U.S. colleges and universities has ballooned by roughly 200,000—growing to more than 764,000 in less than six years, according to data collected by the Institute of International Education and the Department of State. The biggest single group of new international students is from China, which now sends more students than any other country to the U.S. In a trend that is expected to continue, China has increased the number of students it sends to the U.S. by 20 percent every year since 2008, reaching 194,029 last fall.

These new Chinese students have enrolled at American institutions large and small, public and private, with the greatest numbers going to the public, flagship campuses of state universities like the University of California, Los Angeles, the University of Texas at Austin, the University of Washington, or the Big Ten. Big state schools, like Purdue, already had sizable international student populations, but they have increased their undergraduate Chinese student enrollment dramatically, doubling or even quadrupling their total international enrollments in just a few years.

While administrators promote the diversity and global perspectives these new students bring to campus, it’s clear that such high-minded goals are not the only motivation for enrolling large numbers of foreign students. With state spending on higher education declining sharply over the last five years—it’s down an average of 28 percent nationwide—out-of-state and international students who pay full tuition (and sometimes even additional tuition) have kept these institutions in the black. As state assemblies have cut back, the people of China have picked up the tab.

Colleges mostly see this as a win-win situation, solving budget woes and adding to the value of the school’s education at the same time. But with the impact of the boom still reverberating, pockets of dissent are emerging. In states like Washington and California, there are growing complaints that the influx of foreign students is crowding local students out of their own state schools. Meanwhile, at least some Chinese students are complaining that American universities exploit them by charging extra fees. It’s difficult to argue against the valuable opportunities for cultural exchange and public diplomacy that international education provides. But at the current scale, Chinese students have become so concentrated on some campuses that in many ways it’s as if they were attending separate schools within schools.

International students bring a lot of money into the United States, contributing roughly $22 billion to the U.S. economy in 2012, according to one estimate. Francisco Sánchez, the undersecretary for international trade at the Commerce Department, has said the U.S. has “no better export” than higher education, and Larry Summers, former secretary of the treasury and former Harvard president, lists “exporting higher education”—bringing more international students to American institutions—as a key part of his recommendations for economic growth. Many business interests also argue in favor of reforming immigration policy to allow more foreign-born students not only to come to the U.S. but also to remain and work after their studies are complete.

As government support for state schools declines, the tuition paid by foreign students is ever more important. In Indiana, international students bring $688 million in economic benefits, equivalent to 40 percent of what the state spends on higher education every year. At Purdue, the tuition paid by international undergraduates since 2007 accounts for almost half of all the new revenue it has raised through tuition. This is partly because of the expanding enrollment of international students, and partly because of the tuition hikes Purdue has specifically levied on students from abroad. Two years ago, Purdue decided that on top of the $27,646 it already charged all out-of-state students in tuition each year, it would charge incoming international students another $1,000. Last spring, they doubled that fee to $2,000, which will soon add up to an additional $10 million per year for the university.

After the fees doubled last year, the Chinese Students and Scholars Association organized a protest on campus, unfurling banners that read, “We are not cash cows!,” “Education is not a business!,” and “Increase our voice, not our fee.” But the applications from China have continued to roll in. Chinese parents who have spent years saving nest eggs to send their child to university see highly ranked American public schools as a great value compared to private colleges. With growing wealth and a lack of educational infrastructure in China—and millions of single children reaching college age—Chinese parents are willing to pay the price for an American education, which they consider the best in the world.

Up, up, and away: Undergraduates from China account for a large part of the rapid increase in international student visas in recent years.

In the win-win situation that many universities envision, these Chinese families are subsidizing the education of in-state students while enriching the college experience for everyone. But the numbers tell a more complicated story.

According to data on Purdue’s Web site, from 2007 to 2012, while the total campus population, graduate and undergraduate, stayed about flat, the number of students from Indiana fell by 3,323. During the same period, the enrollment of Chinese students increased by 3,156, a nearly one-to-one replacement of Hoosiers for Chinese students. At the undergraduate level, the enrollment of Indiana resident undergrads fell by 3,447, despite Indiana’s high school graduating class increasing roughly 10 percent; international students increased by 2,864. The Great Recession occurred during this period, an event that presumably increased the numbers of Americans trying to get into public schools because their parents could no longer afford pricy private schools.

Purdue is not unique in this pattern. Just across the state border from Purdue at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, there are 268 fewer undergrad students from Illinois today than there were in 2003, and 3,318 more international students.

Six years ago, after administrators at Urbana-Champaign announced plans to enroll more out-of-state undergrads, there was a widespread public outcry. The administrators backed down, promising to keep out-of-state enrollment at roughly 10 or 12 percent. But since then, they’ve quietly enrolled more and more international students—who, like at Purdue, pay even more tuition than American out-of-staters. The percentage of out-of-state and international enrollment grew to 25 percent of last year’s freshman class.

At the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the percentage of in-state residents that make up the freshman class has declined by 8 percent in the past ten years. During the same time period, the percentage of the class made up by international students has jumped from less than 2 percent to 9.6 percent, according to a report produced by the university’s Committee for Undergraduate Recruitment, Admissions, and Financial Aid.

In Washington State, the perception that in-state students have lost their admissions edge to out-of-state and international students became so intense that the legislature passed a bill in 2011 requiring that a minimum of 4,000 Washington residents be admitted in each freshman class. This spring, another bill was proposed that would further raise tuition for international students by 20 percent, with the increased revenue going to the general fund for higher education in the state. The University of Washington protested, saying the increase would drive away international students, and the measure didn’t pass.

Marguerite Roza, who studies the financing of public higher education at the Center on Reinventing Public Education, analyzed the admissions data for the University of Washington, and found that in 2011—prior to the passage of the law requiring in-state quotas—Washingtonians did in fact have to give way to nonresidents. Her study only looked at out-of-state students compared to in-state students, because international students’ admissions profiles are too dissimilar to be compared. But the boom in international students was certainly relevant to her findings, she said, and the fact that they are not in the same admissions pool is significant. “I think the universities see the international students as a source of revenue that won’t affect their [U.S. News & World Report] rankings,” she said. After all, competition for out-of-state U.S. students can drive down a school’s selectivity, average SAT scores, and other measures that are important to the rankings, but international student applications often buoy a school’s selectivity, and those students who are admitted without SAT scores aren’t factored into U.S. News & World Report calculations.

The search for out-of-state tuition dollars has been going on for a long time, but it was somewhat kept in check by a limited pool of students, and the possible loss of prestige from lowering standards. But a limitless supply of international students changes the game quite a bit, Roza said. “People say, ‘Oh well, they’re supporting our kids,’” she said, referring to the financial benefits of having out-of-state and international students. “But they aren’t supporting our kids if our kids aren’t getting in.”

The fact that the international admissions process is so different from the domestic one has also led to questions about how to ensure the integrity of the process, not to mention the quality of the students, especially since foreign recruiting has become big business in China. Officials at Purdue say they don’t recruit in China, and don’t plan to, but the fact is they don’t have to.

Since 2006, Purdue has received a seemingly endless supply of applications from well-qualified, well-financed students from China. As a result, Purdue only accepts 40 percent of international applicants—a much lower rate of acceptance than for Indiana residents or U.S. nonresidents, and on paper the international applicants often have a higher academic profile than other applicant pools. Michael Brzezinski, Purdue’s dean of international programs, argues that concerns over international students’ quality are overblown. “Our international students have better first-year retention rates and graduation rates than the rest of the student body,” he said. “They are doing quite well here.”

Lost in translation: Luodan Li, a Purdue undergraduate from Shanghai, started a Chinese-language campus magazine, Voice, to help Chinese students integrate with their American peers.

That said, directly comparing international and American students can be tricky. For one, the university doesn’t require the SAT or ACT for international admissions. And for another, international students’ applications arrive at the university’s doorstep primarily via for-profit agencies, which, in their most benign form, are like expensive and very attentive guidance counselors. But they range dramatically in their scrupulousness. Recent reports have alleged that agencies in China are falsifying information, inventing student bios, writing student essays, and manipulating transcripts. After all, a good portion of their payment depends on whether their customer is accepted. For admissions committees at U.S. institutions, deciphering whether a prospective international student is qualified, or more qualified than an in-state student, is therefore more difficult than it might seem.

“It’s a classic scenario of a developing market,” said David Hawkins, director of public policy and research for the National Association for College Admission Counseling, about the use of agencies for recruiting student abroad. “The borders are not well determined.” Hawkins’s organization recently released a report recommending best practices for recruiting abroad, a scene that he has characterized as a “gold rush.” The recommendations call for strict guidelines to ensure transparency and institutional accountability in the use of paid agents. But even for universities that don’t pay agents to recruit abroad, gray areas remain in the relationship, Hawkins said, since the university is largely dependent on their services for international applications.

While Chinese students have long performed quite well at the graduate level, there are also concerns that the students in the new wave of Chinese undergraduates are having special difficulties. Not only are they younger, but as undergraduates they face different expectations than do graduate students to engage in classroom discussions and group work, participate in extracurricular activities, and generally contribute to a vibrant, cross-cultural campus vibe that they were ostensibly brought to the university to help create. Unlike graduate-level math, science, or engineering courses, which used to account for the majority of Chinese student enrollment, undergraduate degree programs require students to take a breadth of humanities and social studies classes that often push the limits of their English-language abilities.

Jian Xueqin, the director of Peking University High School’s International Division, summarized the issues that this new wave has brought to campuses in an online column. “I … can’t ignore the stories I’ve heard from colleagues and former students about how Chinese students behave on American campuses,” he wrote. “I’ve heard complaints that Chinese students segregate themselves, and only speak Mandarin. They breeze through the math and science courses, but reading and writing in English frustrate them. Plagiarism and disciplinary violations are rife. Americans, historically accustomed to the stereotypically polite and diligent Chinese student, become overwhelmed when confronted with this new crop.” He worries that the stage is being set for a backlash.

And the dissatisfaction can go both ways, with many Chinese students reporting a general impression that Americans have no interest in learning anything about Chinese culture or attempting to understand them. Emil Cheung, who is from Hong Kong and graduated from Purdue in May, pointed to language as a major barrier for engagement, but also said that both Chinese and American students had a notable lack of interest in crossing the cultural divide. Despite his interest in basketball, Emil said he didn’t manage to make any real American friends. One of the main benefits of attending Purdue, he said, was getting to interact with Chinese students from different regions of China and “learning to speak better Chinese.” In this respect, too, the size of Chinese student populations on large campuses is less than ideal, creating an environment that can allow students to isolate themselves in their own community.

Intent on bridging this cultural divide, Luodan, the Purdue student from Shanghai, has started a magazine for Chinese students to help them integrate on campus. (The latest issue contains a breakdown of the Greek system for international students.) While the magazine is currently mostly in Chinese, Luodan plans to print more English stories and give American students insight into the Chinese community as well. Luodan’s magazine also sends out daily news roundups via text message to Chinese students, helping educate the Chinese student community about things like student senate elections.

Students like Luodan are one of the reasons American universities stand to gain from admitting more international students. He did well in class, provided a valuable addition to Purdue’s undergraduate life, and left a positive mark on the university. And, of course, during his time as an undergraduate his parents infused almost $120,000 in tuition into Purdue’s coffers—and that’s not including room and board and cost of living for four years. Luodan and his family, and the thousands of other Chinese students who have come before and after him these past few years, have arguably helped to keep the doors open at Purdue during tough economic times. This spring, Purdue announced that it would freeze tuition for all students for two years, marking the first time the college has not raised tuition since 1976.

But that doesn’t mean we should disregard all the issues that accompany a historic shift in the numbers and role of international students on American campuses. When viewed through a wider lens it’s impossible to ignore such challenges as the unsavory practices of the international admissions agencies, the poor integration of many international students on campuses, and the displacement of in-state students. And while universities may have liberated themselves somewhat from the fickle purse strings of state legislatures, they have also exposed themselves to the vagaries of foreign governments and immigration regimes. Even if the influx of Chinese students has saved public universities in the short term, a system that relies so heavily on international tuition dollars seems to strike at the core of the universities’ missions to serve the states that have supported them for so many decades. It raises the specter of a downward spiral of state disinvestment and decreasing public support for universities, adding grease to the slippery slope of increasing privatization.

Tim Sands, Purdue’s provost and vice president for academic affairs, said the “land-grant culture” at Purdue, serving the needs of the state as a public institution, was still very important to the university and aligned with its global aspirations, but he also alluded to the thorny discussions the university is having about the direction in which it’s headed. “There’s no question that as your revenue sources change, your stakeholders change as well,” he said.

Calls to recalibrate the enrollment strategy have already begun in states like Washington and California, and while the reactions elsewhere have been more muted, that may change as the budgetary problems in the state legislatures become less dire. Advocating for fewer international students may seem shortsighted or populist to some, but the eagerness of universities to cash in on the global value of American higher education without weighing the consequences seems equally shortsighted, ignoring the long-standing bargain inherent in public education.

If public universities are going to continue to enroll the increasing numbers of students from around the world who are willing to pay top dollar for an American degree, they would do well to remember what is bringing those students here in the first place: widely respected, quality institutions. By improving and regulating the international recruiting and admissions process, expanding enrollment rather than displacing in-state residents, and taking on smaller numbers of international students from a more diverse pool of countries, universities would help to ensure that U.S. higher education remains the envy of the world.