Recessions are, to a great extent, inevitable. But it is not inevitable that they be on the scale of the most recent one, the worst since the 1930s, costing the economy somewhere between $6 trillion and $12 trillion. Nearly 8.7 million jobs were lost, with each of those having untold ripple effects in terms of family life decisions, social mobility, divorces, alcoholism, kids not going to college, depression, and who knows what else on the misery index. The historic scale and devastation resulted from an unusual brew of fraud, regulatory laxity, and deliberate and misguided corporate decisions—much of which was preventable.

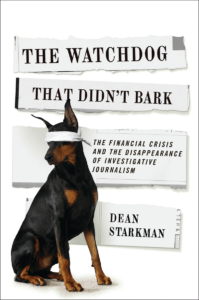

The Watchdog That

Didn’t Bark: The

Financial Crisis and

the Disappearance of

Investigative Journalism,

by Dean Starkman

Columbia University Press, 368 pp.

That the press did not understand and aggressively convey this early enough to stop it must therefore rank as one of the great journalistic failures of recent decades. That good accountability journalism matters may seem obvious, but the dirty little truth is that many people believe we aren’t particularly worse off when the ranks of reporters shrink. As newspapers collapsed, a surprising alliance arose to say, Calm down, it’s not such a big deal. Conservatives rejoiced that the liberal media was shrinking while the conservative media commentariat was growing. Progressives shrugged that all this corporate-owned media was useless anyway in, for instance, stopping the Iraq War—Judith Miller, Judith Miller, Judith Miller—so who cares? And digital evangelists said the dead-wood newspaper industry would be replaced by an even better digital news apparatus, flush with iPhone-wielding citizen reporters and freelance blogger networks.

And it turns out that the difficulty of proving a negative makes it challenging to illustrate how accountability reporting matters. If we have no news about a scandal at city hall this week, is it because there is no corruption, or because the rot just hasn’t been uncovered?

Media critic Dean Starkman grapples with these and other questions in his new must-read book The Watchdog That Didn’t Bark: The Financial Crisis and the Disappearance of Investigative Journalism. Interestingly, Starkman does not argue that the press ignored the scandal entirely but instead describes something more nuanced: that it did pretty well covering the economy in the early stages (2000-2003) but then dropped the ball during the crucial years of 2004-2006, when the subprime market was exploding and something could still have been done to avoid the collapse. Starkman and his colleagues at the Columbia Journalism Review arrived at this conclusion in part by asking major business media to send them their best reporting on the subject. An analysis of the material basically concluded that most of what was written during that crucial time almost never told the story with great detail or alarm.

For the most part, reporters didn’t understand the subprime mortgage industry—nor did they understand that it was based on fraud. “Subprime was where the least sophisticated met the most ruthless,” in Starkman’s devastating phrase—as opposed to being just a slightly riskier (and therefore pricier) version of regular mortgages. A handful of reporters were documenting the predatory nature of the sales operations and their victims. But these stories didn’t tend to get picked up by the national media. And on the few occasions that media outlets did convey the shady nature of the business, they rarely explained that these new mortgages could be tied back directly to major financial players like Lehman, Citicorp, or AIG. “What the reporting failed to see was that the real danger was not in shoddy consumer products per se,” writes Starkman, “but in institutionalized, systemic corruption based on misaligned incentives to put as many of the most vulnerable borrowers into loans under the most onerous terms.”

Part of the problem, Starkman explains, is that most business reporting is geared toward helping investors, small or large, while assessing stock performance on Wall Street. While useful, this approach to assigning, framing, and reporting stories does lead to different questions being asked than if one is taking a “public interest” approach. The increased attention to stock prices coincides with what Starkman calls the rise of “access reporting”—what he dubs the “CNBC-ization” of business journalism. (To justify the special scorn for CNBC, Starkman reminds us that Jim Cramer called out on his March 11, 2007, show that “Bear Stearns is fine!” A week later it had to be bailed out by the Federal Reserve.)

Starkman explains how access reporting works:

I argue that within the journalism “field” a primal conflict has been between access and accountability.… But this is hardly a fair fight. Nearly all advantages in journalism rest with access. The stories are generally shorter and quicker to do. Further, the interests of access reporting and its subjects run in harmony. Powerful leaders are, after all, the sources for much of access reporting’s product. The harmonious relationship can lead to a synergy between reporter and source. Aided by access reporting, the source provides additional scoops. As one effective story follows another, access reporting is able to serve a news organization’s production needs, which tend to be voracious and unending.… Accountability reporting requires time, spaces, expense, risk, and stress. It makes few friends.

Indeed, at the same time the crisis was developing, many business publications were trumpeting the performance of the most implicated companies in the collapse.

Businessweek in 2004, for instance, described how Lehman Brothers had become a “deal making power.” A Fortune profile of Citigroup’s Charles Prince was slightly critical but only because he hadn’t gotten the stock price moving up, not because Citigroup was at the heart of a massive financial debacle that would soon bring it and the economy to their knees.

I would add another element: thanks to improved tools measuring traffic metrics, media managers could judge every piece of content and the financial value of each reporter. And the reality is that the scoop-per-dollar-spent ratio of access reporting is much better than that of accountability reporting. Most of the examples Starkman cites of those who did great journalism were people who spent weeks, if not months, on stories, such as the seven-month investigation by Southern Exposure magazine (notably, a nonprofit), a practice few media operations now tolerate. And it didn’t help that the subprime crisis began right around 2004, when cutbacks in mainstream journalism were accelerating.

One of Starkman’s most astute observations is that the pullback in regulatory restrictions not only coincided with but also fed the journalism problems—and this is the part that reporters tend to not discuss. “The impact of a compromised federal regulatory system profoundly affected not just mortgage lending but journalism’s coverage of it,” he writes. “Reporters rely on regulators for stories, and regulators rely on reporters for cases. Each provides support and public affirmation for the work of the other while educating the public and creating a context for further reform.”

One might think that when regulators pull back, reporters would do more, plugging the gaps left by government watchdogs. But accountability journalism is not countercyclical that way. Indeed, when regulators pull back it makes journalists’ jobs infinitely harder, and vice versa. They tend, therefore, to do less just when they should be doing more.

Starkman spends most of his time analyzing the output of newspapers and magazines, and while he mocks CNBC, he largely ignores network and local TV news (still the sources of news for most Americans), NPR, Fox Business Network, and, for that matter, major providers of digital news such as Huffington Post or Yahoo! He probably figured they were inconsequential players in this drama, and that in and of itself deserves mention.

And I wanted to know: In the few cases when reporters did write the stories critical of financial giants, why didn’t those stories explode on the public scene? Some interviews with the big-time business editors might have shed more light on why they ignored the growing evidence.

The digital world is supposed to be able to take great stories—whether they’re in a small hamlet or New York City—and bring them to massive audiences. Why didn’t that happen? To some extent it’s because the 2004-2006 collapse predated the Twitter explosion and the rise of BuzzFeed, Upworthy, and other online news sources that are focused on accelerating virality. Starkman’s contempt for the digital evangelist types, aggregators, and other newfangled media is unfortunate, and may have blinded him to the profoundly important role that this new amplification system could play in accountability reporting of future scandals.

But we’ll never know: Would those same stories have gotten more traction now because of this new amplification sector? Or would they have been crowded out by lists of “Betty White and Animals” or “Cats Who Think They’re Sushi”?

My guess is that the new media ecosystem—mixing journalism and social media, top down and bottom up—can be very effective at making good journalism more impactful. But as Starkman ably shows, that’s not going to happen if the accountability journalism isn’t done in the first place. And for that we need reporters and institutions who are willing to invest significant sums in potentially low-return reporting that may have small readership but big public impact.

Buy this book from Amazon and support Washington Monthly: The Watchdog That Didn’t Bark: The Financial Crisis and the Disappearance of Investigative Journalism (Columbia Journalism Review Books)