On April 2, the Supreme Court threw out a thirty-eight-year-old provision of campaign finance law, clearing the way for individuals to make an unlimited number of political donations. Depending on which partisan broadcast outlet you get your news from, the McCutcheon v. FEC decision either rescued the First Amendment from the suffocating vice grip of government regulation or murdered democracy as we know it. “They’re not into freedom of speech,” said Rush Limbaugh of the ruling’s liberal critics. “They want to rig every game.” “This is all about freedom?” thundered Al Sharpton on MSNBC. “Freedom for who? The 1 percent?” Sitting in a soundproof glass studio the day after the ruling, radio personality Michael Smerconish has a different take. Rather than pronounce the ruling all good or all bad, he wrestles with its subtler implications.

“I think that money is out of control in politics—in particular, the secretive nature of the giving,” says the fifty-two-year-old Smerconish, who shaves his head and sports a close-cropped Wolf Blitzer-style beard. “That’s abhorrent. I think that’s the biggest problem of all: you ought to at least be able to know who’s funding candidates. But there are some potential upsides to what happened in the Court yesterday.” In particular, he notes, with fewer restrictions on traditional campaign giving, “money might get re-channeled away from Super PAC outlets,” which don’t have to disclose their donors, “and instead put in the hands of candidates and parties,” which do have to disclose their donors. In that sense, he argues, the Supreme Court may have struck an unlikely blow for transparency.

Growing excited, a tangy Philly accent betraying his practiced elocution, Smerconish then proposes an entirely new campaign finance system “that says no corporate giving, no Super PAC, no apparatus like that to shield where the money is coming from.” Instead, individuals would be permitted to give unlimited amounts to whomever they wished. “Would that be a better system than the one we have now? Call now, toll-free. Tell me what you think.”

He opens up the phone lines. “Sean from Tucson” thinks Smerconish is soft-peddling the destructiveness of the decision, and makes the case for publicly funded elections. Smerconish initially disagrees with him—wouldn’t that system favor incumbents?—before reconsidering, midcourse. “Does social media level the playing field?” he asks aloud. “Can you on a viral level spur interest in a candidate, and might that compensate for the incumbent’s upper hand? So maybe I need to rethink what that’s all about.”

In the world of contemporary political talk, Michael Smerconish occupies a unique space. A longtime conservative host out of Philadelphia, he eventually grew alienated from the Tea Party, telling the Washington Post that his AM audience was “too old, too white, too male, and too angry, just like the Republican Party.” So last year he moved his nationally syndicated radio show to the POTUS Channel, an insidery but nonpartisan politics station on the SiriusXM Satellite Radio network. There, for three hours a day, he’s been experimenting with a new kind of talk format aimed at independent-minded listeners, which touts its nonpartisan brand with gravelly voiced promos like “Angry is over” and “Where moderate is not mushy and civil is not sissy.”

Of course, there are plenty of other centrists and independents in public life. Nearly all of them, however, are bland and mind-numbingly tedious. Among them: the business-friendly Third Way zombies who pine for Supreme Leader Bloomberg; the Fox News Democrats-in-Name-Only who crow on endlessly about the national debt; the ex-politicians who grow misty-eyed recalling the halcyon days when everybody was “reaching across the aisle.”

Smerconish is more interesting than these folks thanks largely to his style of banter, which might be described as suburban populist. He is civil and substantive, like a public radio host, but with an amped-up energy level you’re not going to hear from, say, Tom Ashbrook or Diane Rehm. Where National Public Radio tends toward the high-minded, the Michael Smerconish Program is more water cooler—a segment on, say, the situation in the Ukraine might be followed by a discussion about a kid who peed in a public reservoir, or a student at Duke who claims to be a porn star. Smerconish shares his opinions as shamelessly as Bill O’Reilly or Ed Schultz. Yet his views are ideologically unpredictable—sometimes he cuts left, sometimes right—and he puts them forth provisionally, as jumping-off points for discussion, inviting his guests and listeners to challenge him.

Smerconish thinks, in other words, the way most people—at least most people who aren’t hard-core political partisans—actually think about complex issues. They listen. They weigh. They consider. They change their minds when a better argument comes along. They think people who let their opinions be dictated by prefabricated ideologies are idiots. And yet, as any cable viewer or AM listener well knows, such idiocy continues to dominate the world of political talk.

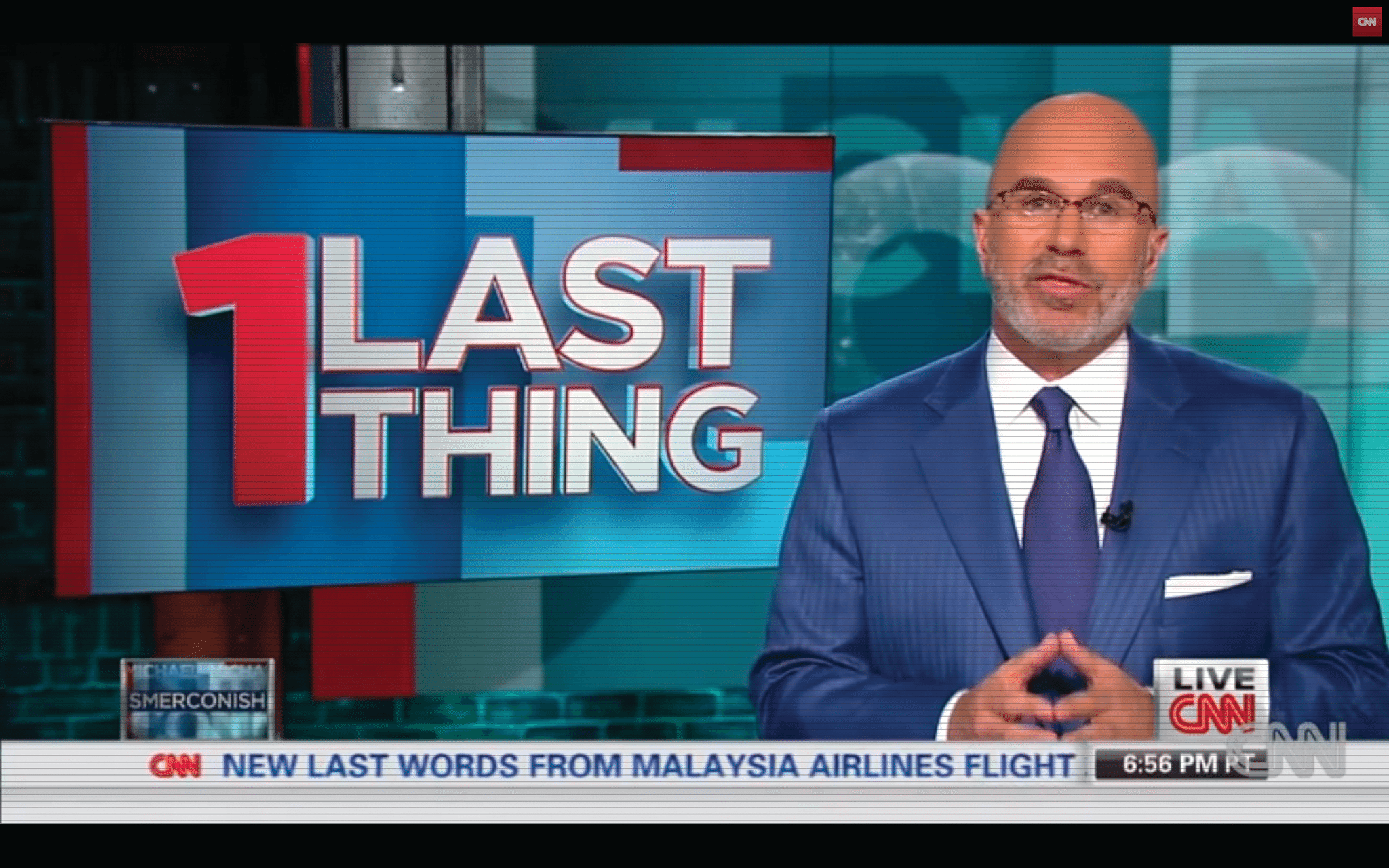

All of which brings us to a question: Can Michael Smerconish’s style of thoughtful, moderate political talk make it in the big leagues of broadcasting, beyond the niche market of satellite radio? We may soon find out. For the past four years, Smerconish has served as Chris Matthews’s regular fill-in host on Hardball. The exposure was good enough that, this spring, CNN gave him his own Saturday-morning show before trying him out as a possible replacement for the departed Piers Morgan, who floundered in the network’s coveted 9 p.m. slot.

It’s easy to see why the network might think Smerconish, with his knack for ideological inclusivity, could offer precisely what it’s been lacking. Fox and MSNBC dominate cable talk ratings in large part because they give their unabashedly partisan audiences unabashedly partisan programming. CNN, by contrast, has stubbornly stuck to its old-school mission of providing nonpartisan news and analysis. That serves the network well when there are big breaking stories to report. But on days that lack the inherent drama of a big news event, it languishes. So far, nothing it’s tried has worked—certainly not the stuffed-suit Beltway consensus spewers and tiresome spectacles like Crossfire that suffuse its broadcasts.

But the instinct to stick to nonpartisan programming isn’t necessarily wrong. There is a vast, untapped middle that would seem to be exactly in CNN’s wheelhouse. A January Gallup survey found that a record 42 percent of Americans identify as Independent rather than Democrat or Republican, a constituency that would seem to be turned off by extremist politics and their cable shoutfest equivalents. So why can’t CNN—or anyone else—capture these viewers?

One reason is that while a large chunk of them identify as moderates, moderates are in fact a quite diverse constituency. As the pollster Stefan Hankin has noted, the states with the highest percentage of moderates are Rhode Island and Alaska. But in Rhode Island, they’re socially liberal and fiscally conservative, and they lean Democratic, while in Alaska, they’re libertarian and lean Republican. The point is: Nobody—politician, pundit, satirist—has found a way to appeal to all of them. And so, much of the country just watches SportsCenter or Here Comes Honey Boo Boo and ignores political talk altogether.

While Smerconish has opinions that a Rhode Island moderate might disagree with, he doesn’t express them in a way that would turn the Rhode Island moderate off. Which leads us to another hypothesis about the untapped middle: Maybe there just hasn’t been a centrist media figure entertaining or thought provoking enough to hold its attention. Smerconish thinks he’s that guy. If he’s right, he’s discovered the media equivalent of cold fusion, the elusive formula that would destabilize the Fox/MSNBC cable hegemony.

But his aim is even grander than that. “I see a causal connection between the polarization in the country and the polarization in the media, with the media leading the path,” Smerconish tells me after one of his shows in late February. “There’s a vacuum out there that can be filled.” If blowhard commentary ruined politics, he’s saying, non-blowhard commentary can save it.

Smerconish grew up in middle-class Doylestown, Pennsylvania, thirty miles north of Philadelphia. His mother was a successful real estate agent whose name is still plastered all over town. (Lavinia, his wife, is also a well-known realtor, on Philadelphia’s wealthy Main Line, where realtors are indeed well known because house buying is the area’s dominant spectator sport. He also has four children and, while we’re at it, a donkey farm in his expansive Villanova backyard.) His father, who worked as a public school guidance counselor, ran unsuccessfully for state representative in 1980. That fall, as a freshman in college, young Smerconish took it upon himself to organize the Lehigh University Youth for Reagan-Bush group and became a reliable grunt for the campaign’s local efforts. In 1986, as a twenty-four-year-old law student at the University of Pennsylvania, he ran for the statehouse himself, losing by 400 votes and building a reputation in GOP circles.

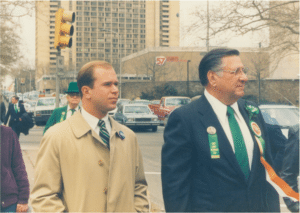

After the election, Arlen Specter invited him to work on his Senate campaign. A year later, Smerconish helped manage Frank Rizzo’s 1987 run for mayor of Philadelphia. Rizzo—who in the 1960s patrolled the city as a skull-cracking police commissioner, then served two terms in city hall in the ’70s—had switched from Democrat to Republican before the election, and tapped Smerconish to help him navigate the new terrain. Smerconish charmed him and quickly gained entrée into his inner circle. Rizzo lost the race, but their friendship helped Smerconish score his next gig, working under Jack Kemp in the George H. W. Bush administration’s Department of Housing and Urban Development. “I remember Smerconish, because he ran the most intense, thorough, and aggressive campaign that anybody ran to become a regional administrator,” says Scott Reed, who was then Kemp’s chief of staff and is now a political strategist at the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. “Rizzo wrote a beautiful letter endorsing him, which kind of caught our eye.”

Much of this history probably represents a natural progression for a hungry young political operative. “He is heat-seekingly ambitious,” says the writer Buzz Bissinger, who says he’s known Smerconish since he was a “toady” for Rizzo. (They once got into a Friday Night Lights-related screaming match on the radio, before later making up at a bar mitzvah.) But his early political resume shouldn’t be discounted either. Kemp’s innovative, humane approach to public housing policy—despite his supply-side bona fides—isn’t hard to see in Smerconish’s own compassionate fiscal conservatism.

His law-and-order fetish, meanwhile, hints at Rizzo’s influence. Smerconish’s book Murdered by Mumia was cowritten with the widow of the Philadelphia police officer shot by a man named Mumia Abu-Jamal. (In March, the U.S. Senate rejected Obama’s nomination of Debu Adegbile to head the Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division largely because he had once done legal work appealing Abu-Jamal’s death sentence.) Before that came Flying Blind, a book-length argument in favor of racial profiling in airports, premised on the heuristic that terrorists tend not to look like your blue-haired great-auntie. His latest nonfiction book, Instinct, lionized a lone U.S. customs officer who stopped 9/11’s “20th hijacker.”

By the time he got into the book publishing game, Smerconish was a drive-time Philly radio fixture. He had started out in broadcasting in the early 1990s, filling in at odd hours and weekends while working full-time as a trial lawyer. (Joe Scarborough too began his career as a trial lawyer. That Smerconish and he occupy similar ideological territory perhaps relates to their shared biography; the trial bar isn’t exactly rife with Republicans.) He gave up the law by the early 2000s, but his legal expertise was integral to raising his media profile. In 2003, he chested Attorneys at Law, a short-lived CNN program with Jeff Toobin and someone from Court TV. After that came regular guest-hosting duties on Scarborough Country and, from there, incongruous standing gigs on both Bill O’Reilly’s radio show and Hardball. The two studios were down the street from one another in midtown Manhattan. “I would get off the air on O’Reilly,” he jokes, “and I would walk north three blocks to MSNBC and I would say, ‘I’m not sure if I’m going to get shot in the back or shot in the chest.’ ”

Laboratory of democracy: In his secret POTUS Channel studio somewhere in suburban Philadelphia,Michael Smerconish experiments with a new “suburban populist” style of talk radio aimed at moderate listeners. Here he interviews fellow Philly native Chris Matthews, whose MSNBC show Hardball Smerconish used to guest-host. Credit: Getty Images

While the TV experience was a boon to his name recognition, it also hampered his ability to be taken seriously. As a completely bald, wild-eyed AM host hawking anti-terrorism books (this was pre-beard), the Michael Smerconish of the mid-2000s had an unhinged quality about him that didn’t do him any favors when he appeared on The Colbert Report and Real Time with Bill Maher. (“This PC craziness,” Smerconish told Colbert in 2006, “is a form of cancer.” “It’s exactly like cancer,” Colbert responded.) But his obsession with terrorism and national security also led him out of the wilderness, to Barack Obama.

“I was drinking the Kool-Aid, and saying things like, ‘We need to fight ’em over there, so we don’t have to fight them here,’ ” Smerconish tells me. In the run-up to the 2008 presidential election he became convinced that the U.S. was wasting its time in Iraq and Afghanistan and was letting Osama bin Laden and al-Qaeda run wild in Pakistan. When then Senator Obama came on his show and echoed his criticism—a criticism John McCain and Hillary Clinton did not share—Smerconish had found his man. In October 2008, he switched his registration from Republican to Independent and endorsed Obama on air.

“I think a lot of people say, ‘I didn’t leave, the party left me,’ ” says Mother Jones Washington bureau chief David Corn, whom Smerconish regularly interviewed on Hardball. “I think he’s one of those guys who can say that with a degree of legitimacy.” Matthews agrees, adding that Smerconish appeals to a very specific type of lapsed conservative: “The kind of people that catch the train in the morning, men especially. They see the Broadway posters on the wall of the train station, read the New York Times, know what’s going on, tend to vote moderate Republican, and are very decisive in elections.”

Smerconish, with his Oliver Peoples glasses and pocket squares and sockless loafers, is very much a product of Philadelphia’s moneyed burbs. And his politics now have a good deal in common with those of the swing-state purple counties that have propelled Obama to two terms in the White House. In his 2009 memoir Morning Drive, Smerconish laid out a “Suburban Manifesto” designed to save the Republican Party from itself. Among other things, it advocated for gay rights, over-the-counter birth control, and getting out of Iraq. It advocated against porous border control, heavy-handed campaign finance regulation, and bloated entitlement spending.

If there’s a mainstream media figure who most resembles Smerconish, it’s MSNBC’s Joe Scarborough. Both are strong on defense, laissez-faire on social issues, and have massive hard-ons for the Simpson-Bowles deficit-reduction plan. Both have made names for themselves as conservative apostates willing to attack the increasing radicalization of the GOP. But where Scarborough still identifies with the Republican Party, Smerconish is an Independent whose style is more inquisitive and measured, with no hint of southern conservative bravado. And while the set of Morning Joe serves as a salon for the power elite, there is a quotidian, variety-show quality to Smerconish’s program, honed from years on AM radio.

It was the uglier side of AM, however, that drove Smerconish away from terrestrial radio. After endorsing Obama, his ratings didn’t fall much; in 2013, he was broadcast in eighty markets and averaged about 1.75 million viewers a week, according to figures provided by Talkers magazine, making him roughly the tenth-most-popular talk show host in the country. Still, he felt increasingly isolated in his field. His own admiration for the president (“I think he’s got a great intellect, I think he’s morally beyond approach”) was at odds with the unflagging vitriol Obama was getting from nearly everybody else in talk radio. When he left his Philadelphia station last spring, he said it was his own choice. The station’s director suggested the parting was mutual, telling a reporter that Smerconish “didn’t serve our core values” and that the station “wanted to remain conservative.”

Either way, both agreed that AM talk radio had become an increasingly inhospitable place for someone willing to host Obama on his show seven times. A few years ago, in the midst of his political conversion, Smerconish delivered a keynote address at a National Association of Broadcasters conference in Chicago. “I made the whole pitch about how this business model is going to die, and how it’s not in the country’s best interest because it’s all built on this bullshit debate,” he recalls. “And when the speech ended, they all came up and gave me a sort of ‘Attaboy, we’re glad somebody said it, blah blah blah.’ But they don’t want to be the ones to change, because it’s paying their bills. Because they’re afraid to be the ones to break the mold.”

Michael Smerconish’s SiriusXM studio is located in a tallish office building in the Philadelphia suburbs. Lining the walls are framed photos and newspaper clippings featuring him with favorite politicians (George H. W. Bush, Obama) and interview subjects (Fidel Castro). On the opposite side of the room from Smerconish’s desk is a map of the United States, a constellation of colored pins creating an unscientific tabulation of his callers’ locations. I’m pretty much barred from describing the place any further; he has made me promise not to write about “the location of my studio, what it says on the door, or any identifiers at all.” After he came out for Obama in 2008, many of his AM listeners turned on him. “No one knows we’re here, and I can’t have that get spoiled. There are a lot of kooks out there. I got the emails and the crayon letters to back it up.”

His satellite audience is less rabid, less responsive to talk radio red meat. The day I visit the studio, a little after seven o’clock on a Monday morning in late February, Smerconish and his preternaturally cheerful producer/on-air sidekick, TC Scornavacchi, are planning the day’s show. Currently, this consists of bullshitting about True Detective, which leads to an unlikely appreciation of “Matthew Crawley’s mother” on Downton Abbey, which eventually brings us to Alec Baldwin, who has recently announced his self-imposed media exile in a New York magazine cover story.

“How’s he going to pull that off?” Smerconish says, looking up from an array of newspaper clips on the table in front of him. “All I need to know is that he stands by his story that he didn’t use a homophobic slur. We, like, Zapruder’d that tape.” Scornavacchi, a raven-haired suburban mom with a degree in biology from Harvard, agrees that Baldwin’s word of choice, in telling off a paparazzo, was not, as he claimed, “fathead.” “But you know what,” Smerconish decides, “he’s an unbelievable actor.” Alec Baldwin will be discussed during the third hour.

Also discussed in the third hour is the news that Piers Morgan was canned by CNN after a dispiriting three-year run. It’s a slightly awkward subject to broach, as Smerconish’s own deal with the channel has recently been announced. But during a commercial break, Smerconish decides to skip a dull-sounding segment about the challenges of being a teacher and instead asks TC to bring up Morgan when they come back on air.

There’s a story he wants to tell. A week earlier, he was slated to appear as a guest in the second block of the show, but kept getting bumped back as Morgan obsessed over the Michael Dunn shooting case in Florida. “So I sat there in the greenroom watching what Piers was doing that night,” he says, looking at TC. “I’m not being critical—this is the evolution I have watched. When the show was launched, [Morgan interviewed] Howard Stern for an hour. Piers is very good at one-on-one interviews. He is willing to ask the uncomfortable questions.” Three years later, that long-form style had all but disappeared. “I was getting ready to go on myself. Then, a three-guest panel. They argued. Went to commercial. Argued again. And then I came on. I don’t even know what I was doing there. Talking politics, president’s numbers were in the crapper.” The moral of the story: “I’m sure if I had a clicker in my hand and I had taken a look at MSNBC that hour or if I had looked at Fox that hour, it would have looked very similar.”

The vignette speaks to Smerconish’s recognition of CNN’s impossible struggle: Emulate the aggressive style of Fox and MSNBC, though do it in a completely impartial way. But it’s also emblematic of the way CNN tends to squander the unique abilities of its on-air talent—in this case, forcing Morgan, whose strength is in interviewing celebrities, into acting like a more rabid version of Wolf Blitzer. And it makes you wonder whether CNN would ever let a guy like Smerconish fully be Smerconish in that 9 p.m. slot.

The genesis of that Smerconish, the one broadcasting every morning on the POTUS Channel, comes into focus after the show, at an upscale grocery-cum-deli place near the studio. Five minutes into a lunch of meatball subs, we’re interrupted by a tanned sixtysomething guy named Chuck Schwartz, who used to own the Philly radio station where Smerconish started his broadcasting career. “This is no bullshit, Chuck’s wife signed my first paycheck,” Smerconish says, telling him to pull up a chair. The warm memory of it all washes over us. Chuck and Michael wax nostalgic for a little while about the old nonpartisan universe in which the station used to exist, before Clear Channel Radio and Rush Limbaugh’s world domination, when its marquee show was hosted by a guy who billed himself as “the Gentleman of Broadcasting.” “Chuck is from the era where guys like him owned radio stations,” Smerconish says. “It didn’t matter what the politics were as long as it was engaging. And Chuck was the last guy—the last big market—to bring in Rush Limbaugh. And he did it, kicking and screaming.”

In 1987, the Federal Communications Commission stopped enforcing that most old school of broadcasting bylaws, the Fairness Doctrine, which stipulated that stations devote equal time to liberal and conservative programming. Meanwhile, satellite technology allowed for cheap radio syndication, and cell phones gave rise to call-in shows, giving disaffected male callers a platform on which to feel a little less marginalized. All this was set against a broader backdrop of deregulation, which allowed publicly traded media conglomerates to gobble up smaller stations and streamline them into profit machines. Guess what’s cheap to produce and makes a ton of money? A political talk show.

Following these convulsions, the media landscape changed swiftly. According to a 1995 essay by the media scholar Susan Douglas, the number of talk radio stations in the country ballooned from 238 in 1987 to 875 by 1992. That number has since swelled further, but the growth has been one-sided: there is ten times as much conservative radio programming as there is progressive talk, per one estimate. On the television side, there is a greater balance between the two dominant partisan cable stations, but MSNBC only became a serious player when it began mimicking Fox’s style with outrage-heavy hosts like Keith Olbermann, Ed Schultz, and Rachel Maddow. The problem with all this, as Smerconish tells anyone who will listen, is not simply that political talk has become angry and doctrinaire, but that it’s also largely responsible for polarizing the electorate.

It sounds plausible enough. But is it true? Matthew Levandusky is a political scientist at the University of Pennsylvania who set out to answer that question by recruiting random test subjects, cataloging their political views, exposing them to unhealthy doses of Fox and MSNBC, and then taking their temperature once again. What he found, as he documented in his 2013 book How Partisan Media Polarize America, is that far-left viewers were pushed farther to the left by MSNBC and far-right viewers were pushed farther to the right by Fox. Conservative programming didn’t influence liberals, liberal programming didn’t move conservatives, and those in the middle didn’t budge at all. “No moderate watches Hannity and says, ‘My God, I’ve been conservative the whole time,’” Levandusky says.

Fox and MSNBC are indeed pulling their most loyal viewers to the extremes. Those people, in turn, are more likely to vote in primaries and head to rallies and donate to candidates. So in this sense, partisan media polarize America. But Bill O’Reilly and Rachel Maddow aren’t changing minds. It’s unclear, then, what a host like Michael Smerconish could really do to de-polarize the country, especially considering the factors that are completely out of his control, like highly gerrymandered congressional districts and relaxed campaign finance laws.

Jeffrey Berry, a political scientist at Tufts and the coauthor of the 2014 book The Outrage Industry, dismisses any suggestion that Smerconish could make a dent. “He’s a little more intellectual than the typical radio host, and that makes him a more difficult sell,” Berry says. “It might seem good that he has its own niche, but the market doesn’t support that niche very well.” In other words, according to Berry’s research, we all gripe about overheated media, but it’s the only kind of cable talk that generates any ratings.

Young politico: Michael Smerconish managed Frank Rizzo’s ill-fated 1987 run for mayor of Philadelphia as a Republican (left), having worked the previous year on Arlen Specter’s successful Senate reelection campaign (right). Credit: Courtesy Michael Smerconish

SiriusXM says it does not track ratings for individual shows, and can only tell frustrated reporters that it has twenty-four million subscribers nationwide and estimates double that in listeners. Cable news numbers, by contrast, we have. In 2013, Fox News averaged 1.1 million viewers in prime time, followed by MSNBC at 640,000, and CNN at 568,000. Jeff Zucker, hired away from NBC in 2012 to right the CNN ship, sees Smerconish as a potential solution to the dismal ratings—whatever political scientists like Jeffrey Berry may say. “I think that Michael embodies very much what I want CNN to be,” Zucker tells me. “He calls the world like he sees it and doesn’t play partisan with anything, whether it’s politics, or pop culture, or everyday life.” And Smerconish, for his part, sees the network as an intuitive vehicle for his mission. “The real power rests in the middle, and that’s where the raw numbers are. But the passion exists on the fringe,” he says, adding later, “This CNN opportunity that I have is in some way a referendum on whether people are willing to change their habits.”

Smerconish’s first Saturday-morning show begins on March 8th with a rousing defense of non-hysterical political commentary, followed by an interview with the occasionally hysterical Republican congresswoman from Tennessee, Marsha Blackburn. The international crisis du jour concerns Crimea, and Blackburn has been a harsh, if vague, critic of President Obama’s response to Russia’s annexation of the region.

“How does it serve our interests to portray him as something out of the old, you know, Charles Atlas cartoon where he’s getting sand kicked in the face?” Smerconish asks her. “I see someone who has incrementally increased these drone strike attacks. I see the NSA still spying in the name of national security. I see an air war that was supported in Libya and what I don’t understand is how this equates to weakness.” Blackburn blinks a few times, repeats some hawkish talking points, and Smerconish thanks her for her time. It’s a strong, pointed segment, compared to standard-issue CNN fare. Per Smerconish trademark, the rest of the show is devoted to a pupu platter of topics, from SAT scores to an old New Yorker story on an executed Texas man. The inaugural show, unfortunately, would be the best one for weeks.

Five days later, news broke that Smerconish would be “auditioning” to replace Piers Morgan for a weeklong stretch in early April, alongside more veteran network hands like Don Lemon and Jake Tapper. But that very day also brings a story about a missing Malaysian airplane, and CNN is going all-hands-on-deck. For the next month, the Flight 370 story dominates not only Smerconish’s Saturday-morning show but his entire week in Morgan’s chair, where his producers trot out a depressing lineup of prop-bearing aviation experts wearing ill-fitting suits.

The Monday following the Piers Morgan week, Smerconish and TC conduct an on-air postmortem that serves as a very thinly veiled critique of the network’s Flight 370 coverage. “There was such a difference from what we did on radio and what you did on TV,” TC says, rattling off a laundry list of subjects that they discussed that week on radio but were not broached on CNN, from DeSean Jackson to Cass Sunstein to the movie Noah.

“Just say it,” Smerconish tells her when she’s finished. “It’s just the two of us. I’m back in the office. TC, what you’re saying is, television didn’t resemble—and it didn’t!—here what I do on a day-to-day basis.” “Correct,” she says. He goes on: “Let me say a couple of things. One, it was a great experience for me. Was I frustrated at not being able to do the things you just listed, and that we’ll be doing today, and for the rest of the week? Absolutely.”

CNN’s bread and butter is presidential elections, natural disasters, and, now, air travel quagmires of apparent global intrigue. Its reluctance to deviate from that formula is understandable, even if it means forcing Smerconish to chase down crackpot theories about a disappeared 747. Once the Flight 370 obsession dissipates for good, it’s unclear to what extent Smerconish will get to be himself. In April, the network announced that the 9 p.m. slot would feature a spate of documentary-style programming, while a nightly news roundup would air at 10 p.m., hosted by a revolving cast of talking heads, Smerconish among them. When I ask Zucker if Smerconish can help CNN cater to an audience that Fox and MSNBC repel, he cuts me off. “We are a news channel, they are talk. We are in a different sphere than they are.” Smerconish, though, is not a news guy. And if his “referendum” ends up failing, it may not be entirely his fault.

On that day in early March when the Malaysian jetliner story first breaks, I tag along with Smerconish on a trip to the New York home office of Simon & Schuster, which has been tapped by Smerconish’s publisher to distribute his sixth book, Talk, a roman à clef about a Rush Limbaugh type who fakes his rabid conservatism to dominate ratings, before (spoiler alert?) denouncing the right-wing radio industrial complex in an on-air cri de coeur. The idea is for Smerconish to get the sales team amped up about the novel before they try to sell it to Books-A-Million and others. So, champagne is uncorked, introductions are made, and Smerconish launches into an Aaron Sorkin-worthy monologue about the plague of partisan media.

“Saturday mornings in the 1970s, my brother and I, you could find us in our rec room,” he begins. “We’d be watching pro wrestling. This is pretty much a guy thing, I know, but we would be watching our heroes—like George ‘the Animal’ Steel, and Haystacks Calhoun, and the Living Legend Bruno Sammartino, and my favorite—Chief Jay Strongbow.” He pauses. “Look at me now. Because today I work in the media equivalent of the pro wrestling that I used to watch as a kid. That’s what the world of cable television news and talk radio has become.” And finally, the climax: “You know, there’s a good guy and a bad guy, all the fights are predetermined and they’re choreographed. And I’m afraid that too many Americans—and definitely the politicians—can’t distinguish news from entertainment.”

I’ve heard this all before—he opened his CNN show and closed his novel with the same speech. But I still find something quaint about the scene: a team of old-school book salesmen, looking ever the rumpled part, preparing to hawk a title to a handful of bricks-and-mortar chain bookstores teetering on the edge of insolvency; in front of them, a quixotic pundit railing against his industry’s meal ticket. In the book version of this tirade, Smerconish’s lead character shifts an entire media paradigm in the heat of a presidential election. In this version, twenty people clap, ask a few follow-up questions, and then bid him good-bye.

After the pep rally, Smerconish and I take the elevator back down to the lobby. On our way out the door, we pass an entire glass case devoted to Rush Limbaugh books. Outside, staring at the News Corp building and the SiriusXM offices across the street, I ask him who he typically sees when he’s in New York. “It’s funny, I’m kind of a loner when I’m here,” he says. “I’m always in search of the place where I can get something at the bar and not feel like a loser.” We talk a little longer, before shaking hands and parting ways. Then he walks off to eat a plate of spaghetti and drink a Manhattan, at a bar, alone.