In 1925, one of college football’s biggest stars did the unthinkable. Harold “Red” Grange, described by the famous sportswriter Damon Runyan as “three or four men rolled into one for football purposes,” decided to leave college early in order to play in the National Football League.

While no fan today would begrudge an All-American athlete for going pro without his diploma, things were different for Grange. The NFL was only a few years old, and his decision to take the money in the pros before finishing his degree at the University of Illinois was a controversial one. It was especially reviled by Robert Zuppke, his coach at Illinois.

As the story goes, Grange broke the news to Zuppke before promising to return to finish his degree. “If I have anything to do with it you won’t come back here,” Zuppke replied, furious that a respectable college man would drop out and try to make a living off playing a game. “But Coach,” Grange said. “You make money off of football. Why can’t I make money off of football?”

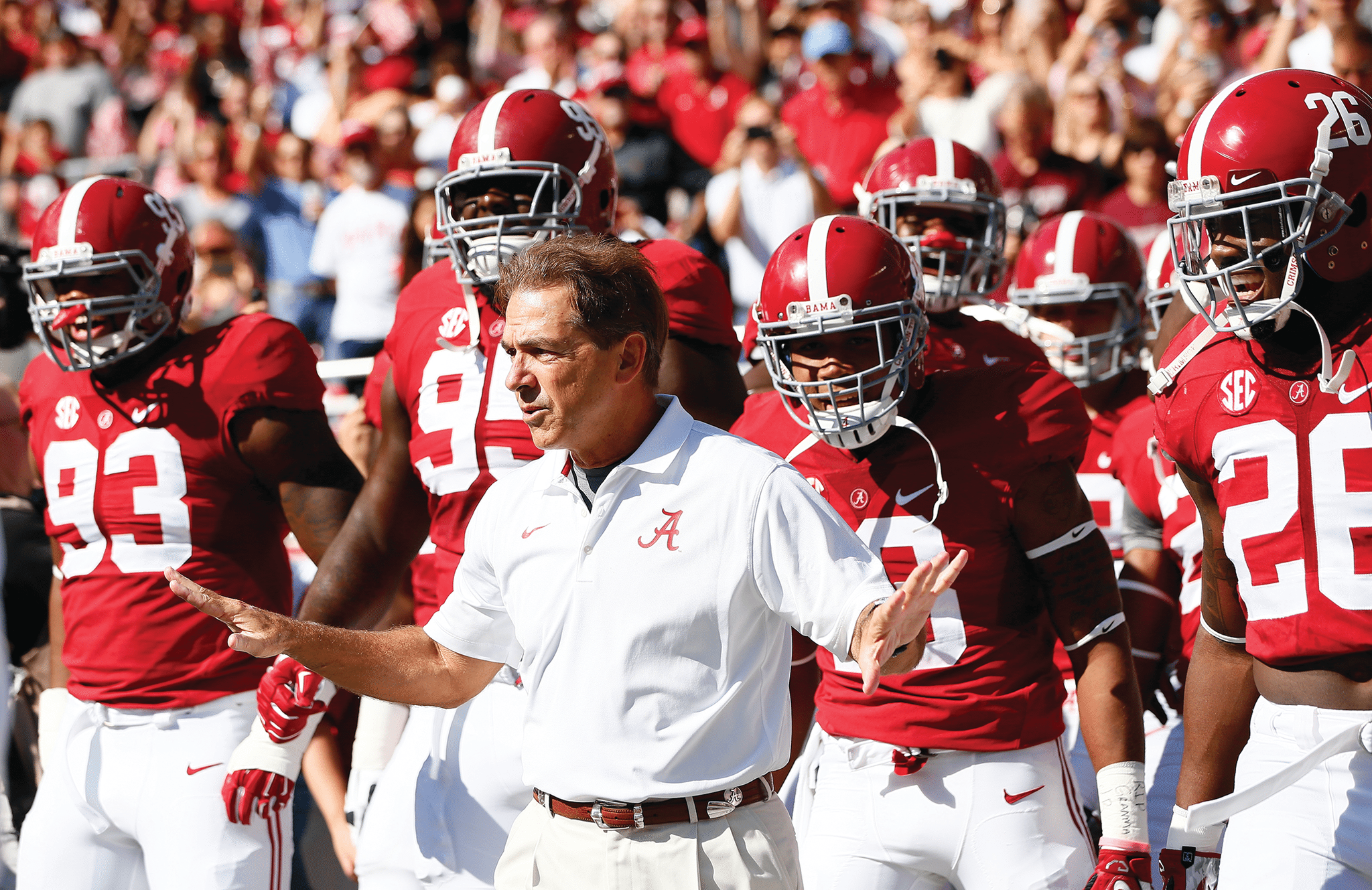

It’s a question that has underscored the development of modern college football ever since. Aside from scholarships and (some) health insurance, the players remain unpaid. They are also subject to draconian National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) rules that banish them to hell for such sins as signing an autograph for cash or selling a jersey. Meanwhile their coaches enjoy ever-swelling salaries, bonuses, paid media appearances, and other perks like free housing. According to Newsday, the average compensation for the 108 football coaches in the NCAA’s highest division is $1.75 million. That’s up 75 percent since 2007. Alabama’s Nick Saban, college football’s highest-paid coach, will earn a guaranteed $55.2 million if he fulfills the eight-year term of his contract.

This widening chasm between coaches and players is creating a growing economic, moral, and public relations challenge for college football. A burgeoning chorus of critics is calling out the NCAA for its hypocrisy. Some want market rates for college players, while others want more incremental changes—a combination of stipends, guaranteed four-year scholarships, better medical care, and financial control for players over their likenesses. To those ends, the NCAA is staring down the barrel of multiple antitrust lawsuits and other litigation over concussion liability, while an attempt by football players at Northwestern University to unionize is awaiting a ruling by the National Labor Relations Board.

Since school athletic departments have to commit their revenue back into sports, money not spent on stipends and other direct benefits for athletes helps inflate those massive coaching salaries. But the difference wasn’t always so stark. More than a century ago, the very idea of paying coaches was up for debate. The arguments against it looked very similar to the arguments against paying players, right down to the concern for the college game’s amateur spirit.

But as football evolved, coaches were elevated above players, rising to become salaried employees, tenured professors, and, eventually, living legends who could demand millions to ply their trade. They broke down the walls of amateurism at the expense of athletes, whose own push for compensation hasn’t gone much further than paid tuition.

In the nineteenth century, many football coaches weren’t paid—or at least weren’t paid specifically for football. Some were graduate volunteers, some were physical education professors or general athletic trainers. Either way, winning football games was not their primary job.

That began to change as the century turned, with more and more schools giving coaches salaries and keeping them around full time to focus on the football team. Harvard was emblematic of the shift. The Crimson football team traditionally had the team captain select a recent graduate to be the (unpaid) coach. In 1901, that coach was Bill Reid, who led the team to an undefeated season capped off by a 22-0 win over bitter rival Yale.

The Harvard administration resisted calls to bring in a professional head coach for the football team, citing the school’s reverence for the ideal of amateurism. But a strong counterargument came in the form of three straight shutout losses to Yale, and Harvard decided to offer Reid $7,000—about $180,000 in today’s money—to return as a full-time coach in 1905.

Reid knew exactly why he was hired. “I don’t care how much of a student a fellow cares to be at other times,” he wrote in his diary days before Harvard’s pivotal rivalry game. “I don’t see how a man can help feeling that hardly anything is more important than to beat Yale.”

His pursuit of that goal led to quite a few strategies that would not be out of place at one of today’s big-time NCAA programs. Reid wrote in his diary of covering up player injuries, finding tutors and meeting with professors to keep players academically eligible, and even spying on Yale to see what kind of equipment they were using. Harvard only lost twice in his two seasons as a professional coach—but both were 6-0 losses to Yale.

By the 1920s, the example of Reid and other highly paid coaches like Fielding Yost and John Heisman had become the norm. Football coaches around the country were salaried employees concentrating on sports full time. The transition wasn’t smooth, and plenty of college officials, sportswriters, and fans reacted with horror to the loss of the amateur spirit and the apparent rise of mercenary coaches who cared only for football and would eschew university loyalty to work for the highest bidder. A 1906 editorial in Hearst’s International decried the evils of “corporately professional football,” saying,

University athletics to all intents and purposes are professional, even though the members of a team may be amateurs. As it is now played, the game of football is not a struggle between students, but between coaches. To a certain extent this situation would be modified if the coaches became members of the instructional staff and were given other duties than that of merely preparing a group of men to beat another group of men in football.

In 1905, the American Physical Education Review weighed in, coming down hard on the “direct evils resulting from an inordinate desire to win at any cost.” The journal chastised “several colleges that pay $3,000 to their football coach”—the equivalent of about $80,000 today—and knocked their recruiting practices:

One of the most serious evils in college and school athletics today is the practice of offering inducements to promising athletes to enter some particular school or college. There are colleges that make a practice of looking up all the promising athletes in the secondary schools and offering them inducements to enter their particular college. These inducements range all the way from free tuition to all expenses, including tuition, board, room, laundry, and pocket money.

(Recruiting and offering scholarships, the very basis of Division I college football today, were not yet widely accepted as legitimate practices.)

Even more than a decade after offering Bill Reid $7,000 to beat Yale, the Harvard community wasn’t sold on the idea either. A 1922 issue of the Harvard Graduates’ Magazine saw writers calling for the school to go back to unpaid graduate coaches.

We await the day when all coaching of college football teams shall be voluntary, carried on for love and not for hire. We would in fact welcome the day when that condition should exist at Harvard, whether any other college accepted it or not. To place amateur athletics under the control of paid and therefore professional coaches is to weaken the amateur spirit. The members of a team are not paid to win, but the coach of a team is paid to make them win; that is, we think, the indisputable truth.

One massive change during this time period that helped lock in paid coaches—and never paid athletes—was the creation of the National Collegiate Athletic Association. Started as the Intercollegiate Athletic Association of the United States in 1906 before changing its name four years later, the NCAA was formed in response to massive safety concerns with college football. (At least eighteen college and amateur players died from football injuries in 1905 alone.)

In addition to setting new football safety standards, the NCAA began making official rules to govern recruiting and scholarships. While some protested the changes, feeling that football would lose its physical edge with new safety precautions (sound familiar?), the new regulations, postseason play, and eventual television coverage helped make the sport more popular than ever.

For coaches, though, a PR shift was in order. Between the rising salaries and professionalization of their jobs (not to mention the increasing recruiting and financial aid allowances for players), the evils many had warned about were essentially coming to pass. The bigger college football got, the more some school officials and alumni began to question where school priorities should really lie. Why were football coaches making so much more than tenured professors at what were supposedly institutions of higher learning?

The solution was simple. “Coaches start to look more and more like professors,” says Brian Ingrassia, a history professor at Middle Tennessee State University. “That’s part of the move—to make college athletics a respectable part of the university.”

Coaches were no longer simply teaching a game; they were teaching students about leadership, manliness, and hard work. It wasn’t just the players on the field who were getting life lessons, either. Every student in the stands was learning by proxy in the bleachers (and, potentially, in a physical education class that the coach might teach one semester a year).

As they realized they could sell their coaching hires as important shapers of young men, universities figured out that they could use their football teams to bring in more publicity, applicants, and money. The legendary Fielding Yost, who turned an enormously successful career coaching the University of Michigan’s football into a tenured spot in the school of education and a job running the athletic department, spoke at his retirement ceremony of “the Spirit of Michigan”: “It is based on a deathless loyalty to Michigan and all her ways. An enthusiasm that makes it second nature for Michigan Men to spread the gospel of their university to the world’s distant outposts. And a conviction that nowhere is there a better university, in any way, than this Michigan of ours.”

Head coaches were no longer volunteer grad students and part-time phys ed trainers. They were moral and sometimes spiritual leaders in the locker room and on campus. Many were tenured professors, and some had salaries in the hundreds of thousands of dollars in today’s money. They were inextricably linked to their schools—relationships that many colleges eventually learned weren’t always for the better.

On October 17, 1969, University of Wyoming football coach Lloyd Eaton kicked all fourteen black players off the team. The next day’s game was against Brigham Young University, a team that had been boycotted by players and students at a few other universities because of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ racist policies.

The group of Wyoming players, who came to be known as the Black 14, had decided to wear black armbands during the BYU game to protest the Mormon church’s teachings. When Eaton warned them after practice that athletes were forbidden from participating in protests, they decided to see him the next morning and talk it over. The players showed up to Eaton’s office wearing their armbands. Eaton later said he gave them ten minutes to explain themselves before dismissing them. “Like hell he gave us 10 minutes,” running back Joe Williams, one of the team’s three captains, told Sports Illustrated a few weeks later. “He came in, sneered at us and yelled that we were off the squad. He said our very presence defied him. He said he has had some good Neeegro boys. Just like that.” While the administration stood behind Eaton, faculty and students protested. The next year, after a 1-9 season, Eaton was fired. He would never coach again.

To college students in the 1960s, it was harder to sell an old football coach as the moral center of the school. That was especially true for black students and athletes, who were even more cognizant of what it meant for a rich white man to be handing down orders to a team of unpaid players. “Some of those athletes start to see this disparity between who’s in charge and who’s actually producing the product,” says Ingrassia. “It looks a lot like indentured servitude.”

The story of the Black 14 at Wyoming was just one of many similar incidents around the country that year, which football-player-turned-English-professor Michael Oriard called “college football’s season of discontent.” That same year, a black player was suspended from Oregon State’s football team for his facial hair, four University of Washington players were suspended after they protested what they called racially discriminatory football decisions, and sixteen University of Indiana players were suspended after they boycotted a practice.

“The protests of black athletes in the late 1960s hit college football at its heart,” Oriard wrote in Slate in 2009. “While white boys like me might still respond to fatherly coaches, racially conscious black athletes were growing less inclined to submit to the paternalism of white father figures.”

Incidents like these were part of the reason universities started to sour on the idea of a football coach as a vital faculty member. Having someone whose only job was to win games would still bring in revenue and attention without as much potential for embarrassment and protest.

Thanks to this attitude change, as well as a general shift in favor of more liberal economics in sports (Major League Baseball players won the right to free agency in 1975), the next few decades saw the rise of the modern college football coach, the potential millionaire who is free to pursue better contracts elsewhere and whose worth to the school is much more tied to his winning percentage than his campus leadership. When the late Penn State coach Joe Paterno was dismissed in 2011 in the wake of the school’s child sexual abuse scandal, he remained a tenured professor in the department of kinesiology. Paterno may have been the last holdover from the previous era, and the last example of why schools stopped holding up their football coaches as moral compasses.

The commentators calling $3,000 salaries evil a century ago would have an aneurysm at the sight of coaching contracts today. Deadspin found last year that college football coaches were the highest-paid state employees in twenty-seven states. (Basketball coaches held that status in another thirteen.) The salary inflation is a direct product of increasing college sports revenue, thanks in large part to massive television deals. Because the colleges and their athletic departments are nonprofit, they need to spend the money they bring in, and since they can’t pay players, there are only so many places that money can go. Head coaches and other athletic staffers are direct beneficiaries. Schools can also pour money into what Clemson economics professor Raymond Sauer calls “player proxies,” or benefits for players that the school is allowed to spend its money on. The biggest example is facilities—a university can build a multimillion-dollar practice complex with hot tubs and video game lounges and other services for players to take advantage of without running afoul of the NCAA.

That may be changing soon. Current and former players have pushed for changes in the way they’re compensated, through lawsuits and other means. Sauer calls the NCAA a “walking anti-trust violation,” while Ingrassia refers to it as a “cartel.”

In August, a U.S. district judge ruled that the NCAA had violated antitrust laws in not allowing players to receive compensation from their names and likenesses. Called the O’Bannon suit after former UCLA basketball player Ed O’Bannon, it was a landmark ruling that the NCAA promptly appealed. “[The NCAA] has to change the rules so they don’t get hit any harder,” Sauer says. “The money’s going to start going to the players. More and more of it. That’s almost written in stone now.”

Cue the handwringing over amateurism and the sanctity of the game. But college football has been here before. Coaches were once unpaid, in many cases serving under the team captain. But they moved up to become professionals, campus icons, and millionaires while players were forbidden from receiving anything more than a scholarship.

Ninety years ago, Red Grange asked his coach why only one of them was allowed to make money off of football. Now, an entire generation of players is asking the same question—and their coaches don’t have an answer.