On Sunday, The New York Times inaugurated series of articles — “Vietnam, ‘67” — that, as its first contributor, US Marine veteran Karl Marlantes, explains, “will examine how events of 1967 and early 1968 shaped Vietnam, America, and the world.”

My own “Vietnam” reminiscence has already been published – right here in the Washington Monthly, in 2001, as part of an article that was prompted by George W. Bush’s dubious ascent to the presidency. But it seems worth sharing again now for the light it sheds on confrontations between citizens and their government – over official lying and coercion in 1967 and, very likely, in the months and years ahead.

Like Marlantes’ essay, which opens with a discussion of the war among Yale students in 1967, mine begins with an encounter among Yale students over that same war a year later. But it takes a very different direction. I offer it again now not only to be sure that this side of Vietnam ‘67 story won’t get lost but in hope that it can help some readers to prepare for whatever lies ahead.

One wintry morning in 1968, as I was plodding across Yale’s Beinecke Plaza in my blue pea coat and corduroy Levis, a junior on my way to a class, I came upon about 40 undergraduates gathered silently around three seniors and the university chaplain, William Sloane Coffin, Jr. One of the seniors, a fine-featured scion of the old republic, was speaking almost inaudibly into a gusting wind and against fear. “The government claims we’re criminals,” he said, as I leaned in to listen, “but we say it’s the government that’s criminal in waging this war.”

He and the other two were handing Coffin their draft cards to forward to the Selective Service System, announcing their refusal of conscription into the Vietnam War upon graduation six months later.

“Believe me,” Coffin responded, “I know what it’s like to wake up in the morning feeling like a sensitive grain of wheat, looking at a millstone.” He did know, having seen dangerous duty in Eastern Europe at the end of World War II as an agent in the Office of Strategic Services, the forerunner of the C.I.A. But his remark carried a ray of Calvinist humor, a jaunty defiance of established power in the name of a higher power, and many of us grasped at it, because we were scared. For all we knew, these guys were about to be arrested on the spot. All of us carried identical draft cards in our wallets, and we felt arrested morally by their example.

Coffin was there to bless — in an American civic idiom that too few Americans now understand — a kind of courage that too few self-proclaimed patriots understand. Just a few yards from where we stood, the names of hundreds of Yale men who’d perished in wars stood inscribed in icy marble under the admonition, “Courage disdains fame and wins it.” The three living young men before us were disdaining fame, but with scant prospect of even a memorial’s posthumous regard.

Yet something in their bearing made them seem intrepidly “American” to me at that moment, as Rosa Parks had been only a dozen years earlier in refusing to move to the back of a bus in Montgomery, Alabama. The quiet dignity of Parks’ performance had credited her white oppressors with some integrity even while exposing their shortcomings, thereby reconstituting the civic culture of the republic, not damning it as eternally racist.

Now, as the seniors before us pledged their lives, fortunes and sacred honor to resist the United States Government in the name of a spirit transcending “blood and soil” patriotism and Cold War ideology, the spirit of the republic itself seemed to be rising from slumber and walking again, re-moralizing the state and the law. And as Coffin closed the demonstration with Dylan Thomas’ admonition, “Do not go gentle into that good night. Rage, rage against the dying of the light,” the silent, wild confusion I was feeling gave way to something like awe.

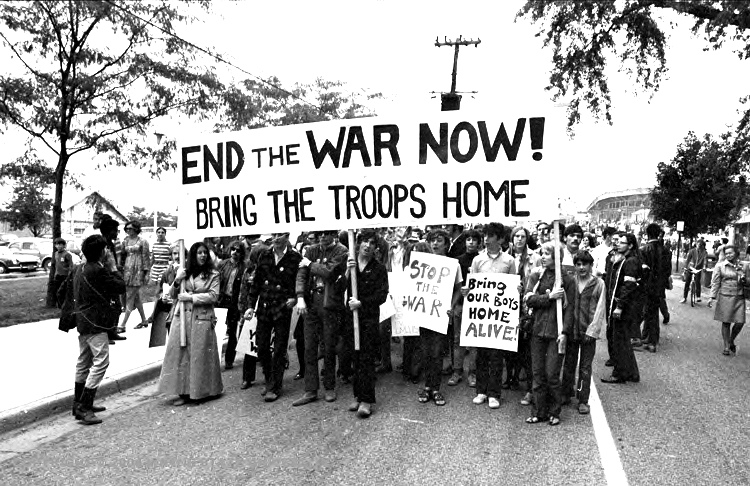

“The great glory of American democracy is the right to protest for right,” Martin Luther King Jr. had said. The German philosopher Jurgen Habermas called such protests manifestations of “constitutional patriotism,” marveling as Americans resisted the state not on behalf of nationalist or racialist glory but for a venture testing whether, as Lincoln had put it, a republic requiring a higher faith and courage might endure.

When I described the demonstration years later to a neoconservative professor, he dismissed it as “the elite moralism of kids afraid to get their hands dirty in war.” But they had been willing to get their hands dirty in prison and as lifelong felons.

Edward Gibbon noted in The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire that republican citizens slid almost imperceptibly into imperial submission when they “no longer possessed that public courage which is nourished by the love of independence, the sense of national honor, the presence of danger, and the habit of command” and when they “received laws and governors from the will of their sovereign and trusted for their defense to a mercenary army….” They “would submit slavery,” Augustus, the first emperor, understood, “provided they were respectfully assured that they still enjoyed their ancient freedom.”

Far from trusting our defense from a mercenary army, the draft resisters were rejecting the official lie that our defense required the war in Vietnam. Years later, noticing a label on one of my T-shirts reading, “Made in Vietnam,” I understood that a “Communist” nation had been absorbed into the world-capitalist economy despite our own nation’s defeat in a war that had cost more than 50,000 American and countless Vietnamese lives. What I’d witnessed that cold morning on Beinecke Plaza inflected forever my understanding of the kind of courage that republican citizenship sometimes requires.

I didn’t have it in me to resist the draft outright. I performed two years’ alternative-to-military service as a conscientious objector after risking imprisonment when my application was rejected on the first round. Even though Robert MacNamara, an architect of the war, acknowledged decades later that it had been undertaken with deceit and delusion (as was the Iraq War), I’ve never faulted anyone who served in it out of a sense of duty or conviction. In fact, I’ve honored some of them even though I believe they were mistaken, and even though I don’t believe that courage and bloodshed on the battlefield automatically sanctify war-makers’ deceits and delusions. My Vietnam lesson is that it’s those who duck any obligation to be counted, one way or the other, who most endanger a republic and its freedoms.

Donald Trump may not be as crafty or as war-like as Augustus, but if he humiliates senators who resist him and assembles a private presidential Praetorian Guard and sends signals to vigilantes that they can disrupt protest demonstrations as Hosni Mubarak’s thugs did in Tahrir Square, he’ll be making war on the Constitution, and we will be tested no less severely than those students at Yale were tested. Unless, of course, we duck.