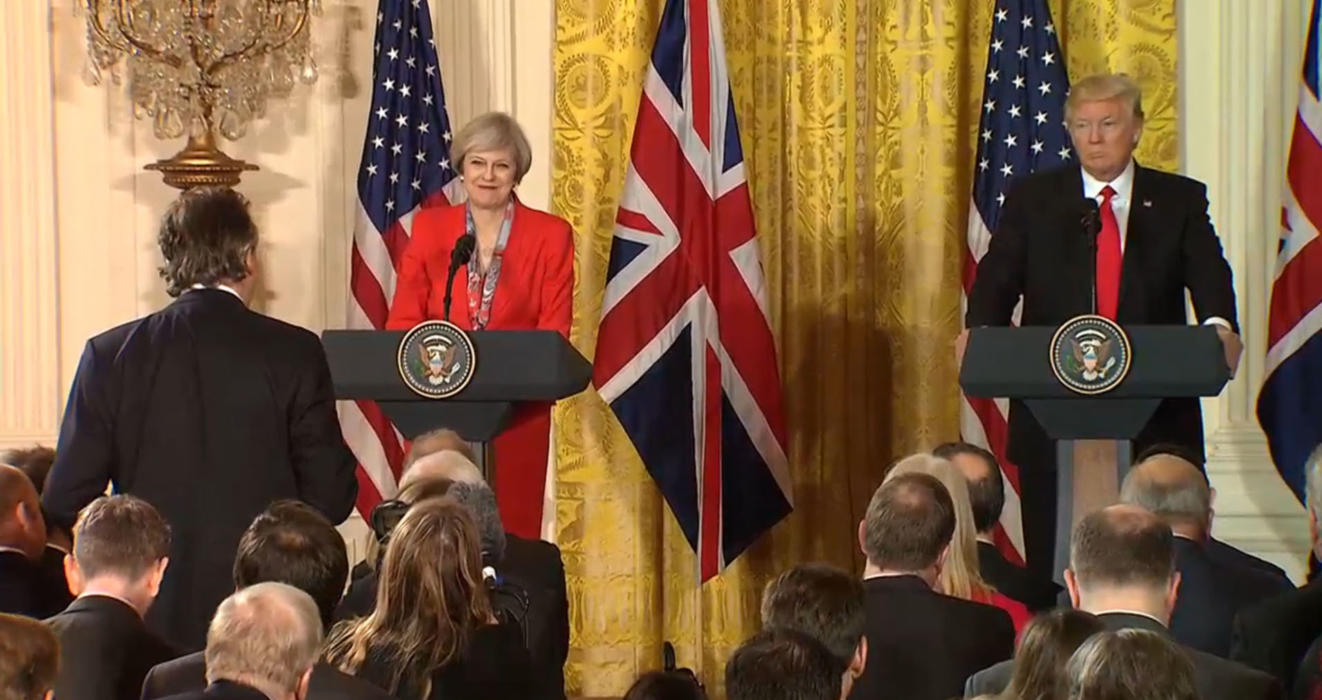

From a distance, it appeared utterly normal, even banal, that our newly minted president’s first official meeting with a head of state was with his British counterpart. Prime Minister Theresa May landed in Philadelphia on Thursday and gave the required speech mentioning the “special relationship” (eight times, by my count) between the United States and Britain. She even made sure to mention Churchill a few times, whose jowled bust, along with golden curtains, now adorn the Oval Office in the White House. President Trump and PM May then met Friday in the White House for lunch and private discussions followed by a joint press conference, the Stars and Stripes and the Union Jack hanging solemnly in the background. Trump, predictably, sullied the moment. He couldn’t string a sentence together and couldn’t help but congratulate himself for “calling” Brexit. He simultaneously doubled down on his odious belief that torture works while apparently handing off executive decision-making to his Secretary of Defense, who just removed his military uniform. To top it all off, he demonstrated an utter lack of decorum towards a British journalist and even towards the crushingly articulate prime minister, answering a question meant for her by saying she has “other things to worry about.”

But, Trump’s menacing incompetence aside, a closer inspection reveals that things were not quite as ordinary as they seemed. In May’s speech in Philadelphia, she made a concerted effort to tie the “special relationship” to international institutions, particularly NATO and the United Nations. Then there was her brief “advice” on Russia, which made it onto every headline and cable news chyron: “engage but beware.” Funnily enough, that was the same advice May received from Parliament and the British press with regards to Trump. But the line that most stood out to me was the following:

“So as we rediscover our confidence together—as you renew your nation just as we renew ours—we have the opportunity—indeed the responsibility—to renew the special relationship for this new age.” [emphasis mine]

May was charged with two major policy tasks: make headway on a possible U.S.-U.K. free trade agreement and reinforce America’s commitments to NATO, which Trump has repeatedly described—to the limitless pleasure of the Kremlin—as obsolescent. The former is of desperate importance to the British government and the British people, who voted in an ill-advised referendum last summer to leave the European Union (E.U.). May, who as Home Secretary earned a reputation of maintaining grace under pressure and for being vociferously against immigration, is in the unenviable position of leading her country under a popular mandate not of her choosing; she was tepidly in favor of staying in the E.U. but has since fully embraced Brexit—the price of admission to 10 Downing Street. May is certainly aware of the economic disaster that will rock Britain under her watch if not enough trade agreements are established in time.

For the British people, close ties to the United States are now of particular psychological importance. Having made a rash decision, they need some kind of vindication, some reassurance that, having cast themselves adrift, they won’t face the consequences on their own, or any consequences at all. Not to be outdone, America made an even more reckless choice in November, which was ardently celebrated by Brexiters, relieved at the thought of having a friend and partner as they sail into the unknown. May seems to share this hope of rediscovering our confidence together.

But there’s plenty of reasons to believe that the British, at least as much as Americans, are laboring under their own illusions. They may have made a stupid decision, but they at least benefit from a competent leader with a solid understanding of the global arena and with mainstream liberal values. America’s stupid decision is its leader, who shares neither the intellectual nor moral capacity of his counterpart. A ship on a disastrous mission is not the same as a ship with a disastrous captain.

May, the daughter of a vicar, wasn’t entirely blind to this heading in, coyly telling reporters on her flight across the Atlantic, “Haven’t you ever noticed, sometimes opposites attract?” Neither was she unaware that she would be meeting a man who is openly obsequious towards Britain’s foremost continental rival, Russia—another trait, it should be noted, shared with Britain’s far-right Brexiters. The day before May’s departure, Russia’s sole aircraft carrier, the dilapidated Admiral Kuznetsov, fresh from its mission bombing Syrian civilians, sailed through the English Channel, an utterly irresponsible show of force by an increasingly strident regime. The British, for their part, responded by dispatching warships and jets to “closely monitor” the Kuznetsov, and Defense Minister Michael Fallon poured scorn on the ship, saying, “We are keeping a close eye on the Admiral Kuznetsov as it skulks back to Russia, a ship of shame whose mission has only extended the suffering of the Syrian people.” The Trump administration has, to my knowledge, kept mum on the incident, which should only encourage more stress tests by the Russians.

The prospect of a bilateral free trade deal is also far from assured. While President Trump has repeatedly said he wants a trade deal with the British, that doesn’t quite square with his protectionist pronouncements. Yet, as the Wall Street Journal pointed out, “The U.S. is a much more important export destination for the U.K. than vice versa, a dynamic that gives the U.S. the upper hand. After the E.U., where nearly half of British exports go, the U.S. is the U.K.’s biggest overseas market.” Also, so long as Britain is a member of the E.U., it cannot “formally negotiate or ratify bilateral trade agreements.” Britain must maintain trade ties with E.U. member states if it’s to prosper after Brexit. Violating E.U. rules, the limits of which Britain is already testing, would hurt its negotiating power. The Financial Times put it most bluntly:

“No matter who is in the White House, the red lines in trade negotiations are often set in Congress, where lobbies such as agriculture and pharmaceuticals remain strong. And whatever rapport Mrs May strikes up with Mr Trump, there is little sentimentality on Capitol Hill about letting warm words about foreign policy special relationships affect the cold reality of trade.”

Taken together, the Prime Minister’s mission to the U.S. begins to resemble her overarching one. The U.S. no longer holds out the promise of economic security, having unmoored itself from its belief in international trade precisely when Britain needs free trade the most, or even loyal friendship, having chosen a leader with little regard for context and much regard for vulgar strongmen like Russian President Vladimir Putin. We are two countries adrift, sharing a wild-eyed glance as we are borne away from each other.