When Clarence Thomas was confirmed for the Supreme Court in 1991, an eerie precedent was set. When Brett Kavanaugh defended himself against Christine Blasey Ford’s allegations, he consecrated a pattern: the fate of a powerful man accused of wrongdoing will be determined by political theatre, not a serious attempt to find out what really happened.

Twenty-seven years ago, the University of Oklahoma law professor Anita Hill recounted the harassment she endured while working as Thomas’s assistant at the Department of Education and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. “He talked about pornographic materials depicting individuals with large penises or large breasts, involved in various sex acts,” she told the Senate Judiciary Committee at the time. “On several occasions, Thomas told me graphically of his own sexual prowess.” Her speech was controlled, dignified, and cautious. Nevertheless, the committee over-scrutinized the most minuscule of details, to the point where Sen. Orrin Hatch even accused her of “erotomania” (delusional sex addiction) and said she may have pulled details of her story from The Exorcist.

Thomas called the hearings a “national disgrace,” and suggested they were, in his infamous words, “a high-tech lynching for uppity blacks who in any way deign to think for themselves.” He was eventually confirmed for the high court by a historically-thin margin: 52-48.

On Thursday, the Stanford University psychology lecturer Christine Blasey Ford detailed how Brett Kavanaugh sexually assaulted her at a party in 1982, when they were both in high school. She spoke nervously, but carefully relayed her story to the panel, with expert descriptions of trauma’s effect on memory. Senator Hatch told reporters afterword that he considered Ford an “attractive, good witness.” Other politicians and media outlets alike deemed Ford credible. Senator Cory Booker even called her “heroic.”

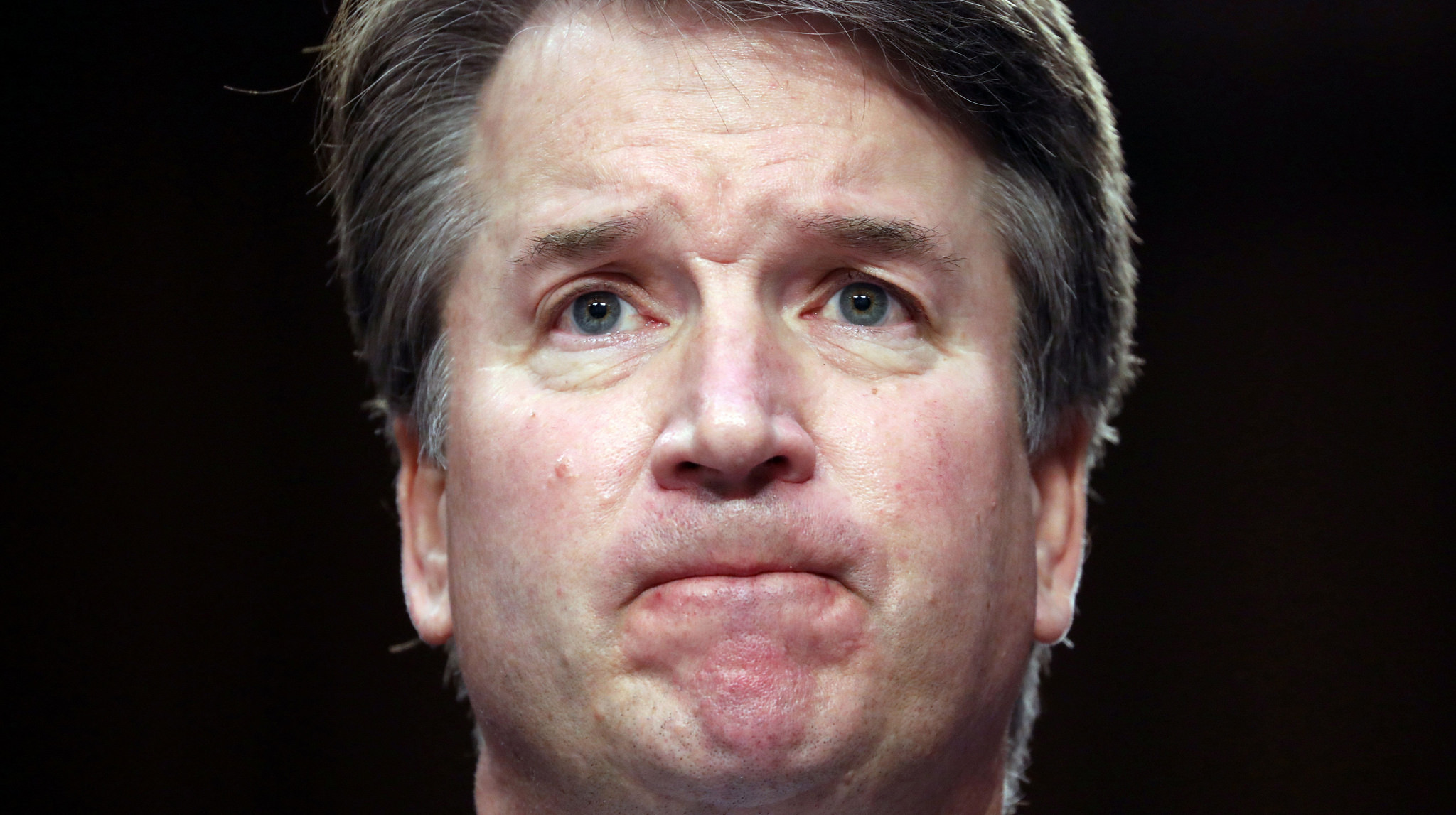

Kavanaugh followed her testimony by berating the Democrats for conspiring against him. Unlike Thomas, who kept relatively cool, the Washington-area native was belligerent and abrasive.

He repeatedly yelled over the senators, threw their inquiries back at them, repeated his qualifications for the position, bragged about getting into Yale, emphasized how much he loved beer, denied assaulting or meeting Blasey, or blacking out from drinking too much alcohol. He also wept periodically. In short, he debased himself during a job interview. Most disturbingly, Kavanaugh disqualified himself for the court by making overtly partisan statements. “This whole two-week effort has been a calculated and orchestrated political hit fueled with apparent pent-up anger about President Trump and the 2016 election, fear that has been unfairly stoked about my judicial record, revenge on behalf of the Clintons, and millions of dollars in money from outside left-wing opposition groups,” he said. “This is a circus.”

Lindsey Graham coddled him. Changing the entire tenure of the proceedings, the South Carolina senator was even more emotional and intense during his questioning. “What you want to do is destroy this guy’s life,” he told Democrats, “hold this seat open, and hope you win in 2020. To my Republican colleagues, if you vote ‘no,’ you’re legitimizing the most despicable thing that I have seen in my time in politics.”

[media-credit name=”Wikimedia Commons” link=”https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Clarence_Thomas_official.jpg” align=”alignright” width=”210″] [/media-credit]

[/media-credit]

Clarence Thomas arose victorious after Hill’s accusations in part because of operatic indignation, especially following the Rodney King assault that took place that spring. Pantomiming Atticus Finch, the noble lawyer from Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, he provoked conflicted Americans with a speech about white supremacy (even though white Republicans chose his story over a black woman’s who lacked political power), preying upon the white guilt of the committee.

Kavanaugh, on the other hand, cited conspiratorial theories about the Democrats, casting them as hellbent on obstructing anything proposed by President Trump. Along with his tearful testimony about the death threats his family received, he positioned himself as the real victim.

That seemed to have worked. On Friday, the Senate Judiciary Committee voted 11-10 to advance Kavanaugh’s nomination to go before the full chamber. All 11 of the Republican committee members who backed him were white men.

But Senators Jeff Flake and Lisa Murkowski both called to delay his confirmation vote until after the FBI has investigated Ford’s claims. They asked for the probe to take no more than a week. While the White House and Mitch McConnell have ceded to their demands, and investigation is currently underway, Kavanaugh will still likely become the next Supreme Court justice. If so, he will have recycled the same tactic Clarence Thomas so masterfully executed when he was accused of sexual misconduct: respond with righteous indignation, and weaponize the accusation by treating it like an instrument of persecution.

These hearings are largely an appeal to pathos, or emotion. Who can invoke what feelings in which committee member and which segment of Americans? Clarence Thomas, after all, was nominated by a Republican president and confirmed by Democratic-majority Senate.

But Kavanaugh has tapped into something deeper for most Republicans. The partisan divide is more acute now than it was in 1991. Many watching this national spectacle will think, for good reason, that victims of sexual assault won’t be believed when they come forward about powerful men. Perhaps that’s because every time they do, it’s powerful men who get to render a judgment.