For most pundits and journalists, Democrats’ successful Election Night was marred by a rural disaster. The New York Times wrote that “the Democratic collapse in rural areas that began to plague their candidates under President Obama worsened.” Vox correspondent Zack Beauchamp argued that “Democratic inroads in the suburbs were offset by huge Republican gains in rural areas.” The Hill summarized such thinking by claiming that “rural voters stormed to the polls in virtually unprecedented numbers, delivering once again for the president they voted for in 2016.” That article quoted Oklahoma GOP representative Tom Cole, who said, “Rural America’s much more Republican than ever before.”

They’re wrong. On the whole, Democrats performed better in rural areas during these midterms than in 2016, which helped the party win some of its most consequential victories.

According to the most recent data from the Cooperative Congressional Election Study (CCES)—a political science survey of more than 50,000 people conducted around election time—roughly five percent of rural Trump voters cast their ballots for a Democrat running for a House seat. That’s not a huge gain, and as Tufts political science professor and CCES co-director Brian Schaffner told me, it was smaller than Democratic improvements in urban and suburban regions. But a five percent improvement is far from meaningless, and a preliminary breakdown of the returns in three critical contests suggests that, in some parts of America, the rural shift to Democratic candidates was even larger. In some races, it ultimately made the difference.

Consider Kansas. Reporting on Democrat Laura Kelly’s upset gubernatorial victory over Republican Kris Kobach, the New York Times noted that Kelly “managed to win by large margins in several populous counties that favored Mr. Trump in 2016.” That’s true, but by itself, it wouldn’t have been enough for her to prevail. Although Kelly lost in Kansas’ rural regions, she lost them by significantly less than Hillary Clinton did two years earlier. In counties with fewer than 35,000 residents, Kelly received roughly 35.8 percent of the vote, compared to Clinton’s 23.5 percent. Kobach, meanwhile, underperformed Trump, winning these regions by 56.1 percent to Trump’s 66.5 percent.

If Kelly and Kobach had matched Clinton and Trump’s vote shares, Kelly would have lost rural Kansas 79,701 to 197,766, instead of receiving 106,499 votes to Kobach’s 166,921. Even if Kelly and Kobach’s urban and suburban vote totals remained the same—if Kelly still managed to win “by large margins in several populous counties that favored Mr. Trump in 2016” and improve in other populous places—Kobach would have won the state by 11,652 votes. A Democrat is governor-elect of Kansas in no small part because of a better performance among rural voters.

My calculations are, necessarily, somewhat imprecise. Tallies are not yet entirely finalized, and what constitutes rural can vary from state to state. Still, it’s difficult not to see the same pattern in Wisconsin, where Democrat Tony Evers defeated governor Scott Walker. Among Wisconsin counties with fewer than 55,000 residents (a larger number for a much bigger state), Evers lost with 43 percent to Walker’s 55.8 percent. But he would have lost the entire election had he performed as poorly as Clinton, who was defeated in these counties 37.8 percent to 56.5 percent. Matching Clinton’s vote share would have cost him 29,537 votes. If even five percent of these lost votes went to Walker, Evers would have been defeated. If Walker had matched Trump’s 2016 Wisconsin rural showing, he would have won reelection by 2,307 votes.

Matthew Schauenburg, a pastor and Democratic activist in Wisconsin’s Grant County, located in the rural western part of the state, told me that Grant County voted for Barack Obama twice before voting for Trump in 2016. Republicans, he explained, won the state with an intense focus on areas in the north and west of Wisconsin—places that Democrats had largely ignored.

“Previously, the state Democratic Party didn’t pay a lot of attention to the more rural areas of Wisconsin,” Schauenburg said. “Slowly, they’ve been realizing that you really have to appeal to all voters and not just your power bases in Milwaukee, Madison, and certain smaller cities like La Crosse.”

Evers understood the importance of visiting rural areas, including a Halloween-day campaign stop in Grant. Along with a strong focus on public education in a state where schools have been hollowed out by Scott Walker’s budget cuts, that helped Evers enormously. On Election Night, Evers returned Grant County to the Democratic column—along with the entire state.

I heard a similar story from Henry Schwaller, a Democrat in Ellis County, Kansas. In 2016, more than 70 percent of Ellis voters chose Trump; only 23 percent opted for Clinton. Laura Kelly improved on this margin dramatically. In 2018, slightly more than 40 percent of the county’s voters cast ballots for Kelly, while 49.3 percent chose Kris Kobach. “She got a really healthy percent of the vote,” Schwaller said. Kelly’s strategy appears similar to that of Evers. Schwaller, a councilman in the county’s largest town, told me that Kelly’s focus on public education and reversing the GOP’s budget cuts helped boost her popularity, including in rural counties.

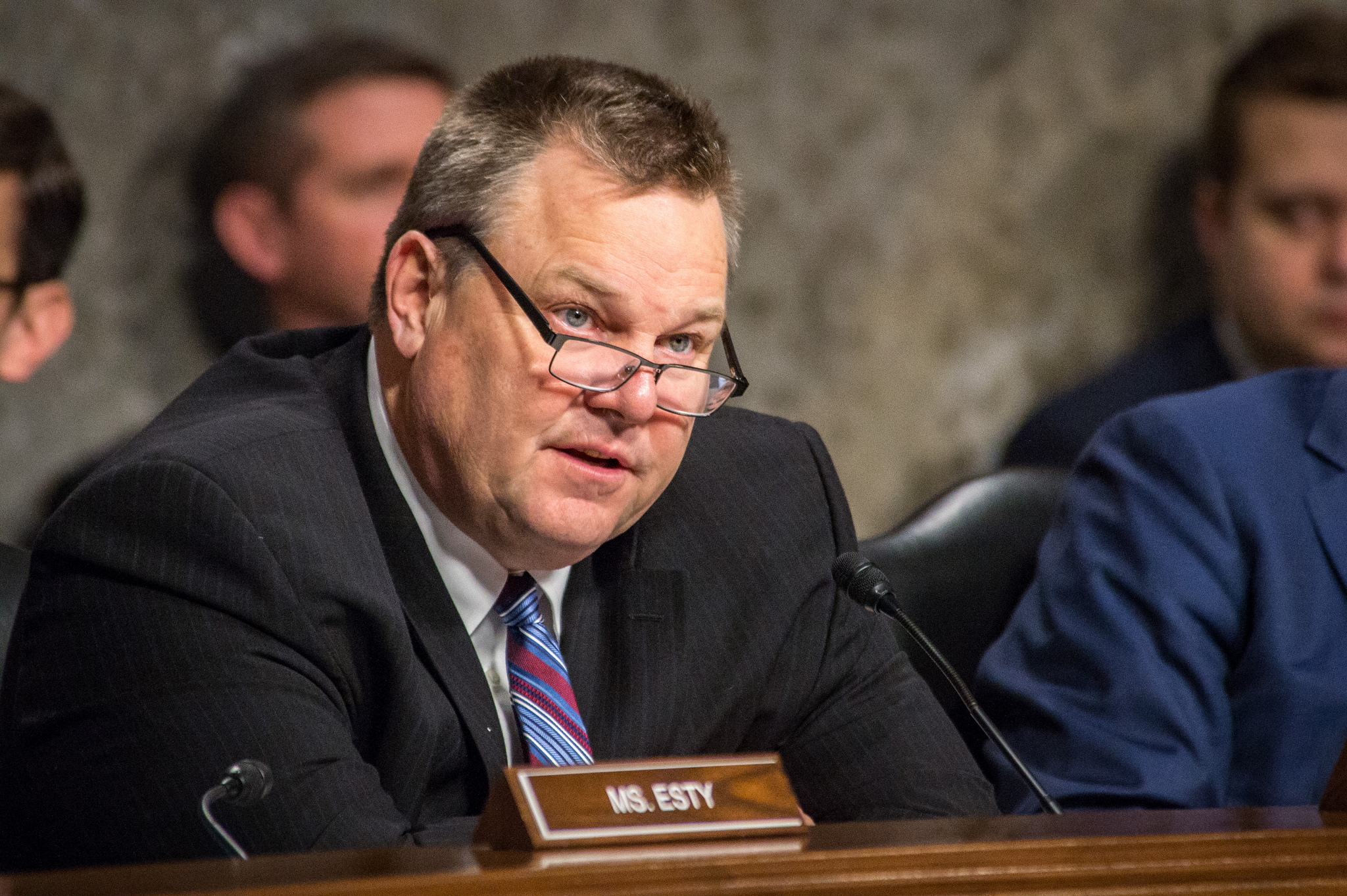

Rural success was also essential to Montana Democratic Senator Jon Tester’s reelection. I calculated the 2018 results in Montana counties with fewer than 20,000 residents (a number that is lower than what I used in Kansas, in large part because Montana is far less populated). Tester received 60,605 votes in these counties, while GOP opponent Matt Rosendale won 80,041. Had Tester only received 28 percent of rural votes, as Clinton did two years prior, he would have lost 20,000 votes statewide. Even if none of these lost Tester votes had been redistributed to Rosendale, Tester still would have lost the overall Senate race by about 4,000 votes.

Emphasizing the impact of rural voters in Montana, or even Kansas, might seem obvious and unfair. Rural voters will clearly be the difference-makers in very rural states. But that’s exactly the point: there are many very rural states. To stay nationally competitive, especially in the Senate, Democrats cannot afford to let Republicans run up the margins in these places.

Liberals are therefore right to worry about the party’s fortunes in the countryside, as many have done since Tuesday’s elections. In wide swaths of America, Democrats did not improve enough from their 2016 margins to save red state Democratic senators. Outside of metropolises, the party is still far away from where it needs to be.

But it wasn’t all bad news. There are Democrats who mustered enough support outside of cities to win typically red states and states that were once blue. Laura Kelly, Tony Evers, and Jon Tester show that by simply performing less poorly in the countryside, Democrats can win statewide. Thankfully, there are Democrats in rural areas who can help these candidates.