America’s politics seem to be intractably broken at the moment. The government is shut down, a patent con man holds the Oval Office, and the entire federal apparatus appears incapable of dealing with a crisis of any magnitude.

There are many explanations for how we got here, but the simplest is that the fatal flaws of a two-party system were masked by the consequences of America’s horrific racist history. From before the Civil War through the Civil Rights era, economic populists aligned with racist segregationists against more socially liberal but economically royalist elites. The counterpressures involved in both uneasy alliances led to mostly functional governments. Once the Democratic Party finally started taking social justice seriously and the Republican Party decided to embrace the Southern Strategy, economic justice and social justice activists started to coalesce against an unholy alliance of bigots, fundamentalists, and greedheads. The parties drifted further apart with little common ground, and a fairly obvious moral divide, one in which each began to see the other less as intellectually misguided than morally evil.

Ironically, even as this was happening, the side of America devoted to addressing our economic, racial, gender, and other intersectional inequalities also started to directly benefit economically from the trend toward urbanization and ever steeper rewards for knowledge-based work over manual labor. Big blue cities started to reap the biggest economic rewards, while most of “flyover country” suffered steeper declines. The white working class saw its fortunes and life expectancies fall vis-a-vis nearly every other segment of the population.

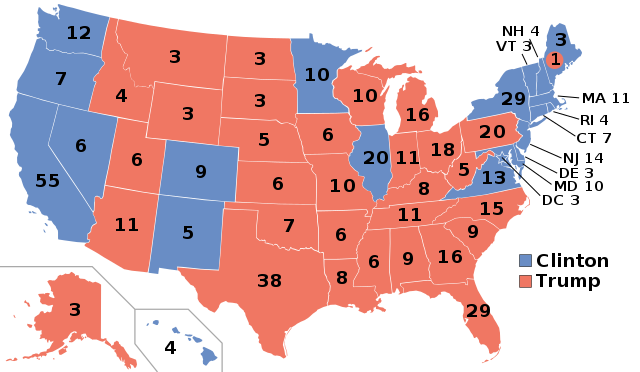

The resulting social pathologies ultimately leading to the election of Donald Trump have been argued incessantly since, with various analysts giving differential weight to the role of economic anxiety and broader bigotries. The goal here isn’t to rehash all of that (my thoughts on it are well documented here and at the American Prospect), but it seems reasonable that increasing racism and a long slide in economic fortunes became mutually reinforcing phenomena just as they have so often in the past. Yes, many comfortable racists and sexists in the suburbs eagerly supported Trump. (Those people are simply called “Republicans” and they voted against Michael Dukakis just as surely for the same reasons.) But so did many rural long-time Democrats and independents who twice voted for Obama–and many of those came back to the fold in 2018, which means that their Trump votes in 2016 can hardly be characterized so simply.

The challenge for Democrats over the next few decades is that the system remains set up to favor smaller and more rural states. Barring the miracle of changes to the constitution itself, that means Democrats will need to try to win in places where they aren’t currently very competitive.

If the pessimists are right and these areas are simply too bigoted to be persuadable, then there is little hope of managing our increasingly pressing crises. We might as well just give up now. But if the economic populists are even half right, there is enormous value to be gained in attempting to help these areas economically.

One subtle way of doing so was highlighted by Daniel Block in this issue of the Washington Monthly: namely, that while we often think of big blue cities and red rural areas, the biggest factor in pushing purple states blue is the growth of mid-size cities in the landlocked states. Minnesota and Wisconsin are a good case in point:

In 2016, the rural parts of both states shifted sharply to the right, matching the national trend. Minnesota, however, stayed blue, while Wisconsin went red. To understand why, take a look at the growth rates of the states’ largest metro areas, both of which voted heavily for Clinton. Between 1970 and 2017, Greater Minneapolis grew at an annual rate of roughly 2 percent, above the national rate of 1.1 percent. The Minneapolis region—home to a variety of corporate giants like Target—now has roughly 3.6 million residents, up from 1.87 million in 1970. By contrast, Greater Milwaukee, buffeted by business closures and a shrinking middle class, grew at an annual rate of only 0.26 percent over the same period.

In Minnesota, Minneapolis’s growth was enough to offset Democratic losses in rural areas. In Wisconsin, Milwaukee’s wasn’t. If Greater Milwaukee had grown at the same rate as Greater Minneapolis, then Clinton would have carried Wisconsin by approximately 16,000 votes instead of losing by roughly 23,000.

What killed the mid-size American city? Not just loss of manufacturing jobs and a dearth of technological education, but a phenomenon familiar less to acolytes of center-left think tanks than to readers of David Dayen and fans of Elizabeth Warren: monopolistic corporate practice. As Block notes:

But regional inequality really took off in the 1980s, when both the Supreme Court and Ronald Reagan’s Department of Justice narrowed the definition of what was enforceable under federal antitrust laws and began approving an enormous number of corporate mergers. The single largest increase in corporate acquisitions in American history happened between 1984 and 1985. This laissez-faire attitude toward monopolies didn’t stop when Reagan left office, or even when Democrats won back the White House. In 1998, for example, Bill Clinton’s administration approved the merger of Exxon and Mobil, then the country’s two largest oil companies. The upshot of these policies is that large firms located in big, economically powerful cities have increasingly captured the market. They have bought out their heartland competitors in industries ranging from banking to retail. The result has been a one-way flow of wealth out of middle America and into elite metropolises.

Greater St. Louis is a prime example of how airline deregulation and the demise of antitrust laws can suck the vitality out of a prominent city. St. Louis was once home to a vibrant collection of internationally competitive corporations and—given its location at America’s center—was a transportation hub and business convention destination. But then it was hit with the by-products of pro-monopoly government policies. Locally headquartered Ozark Airlines was bought in 1986 by Trans World Airlines, which was then bought by Chicago-headquartered American Airlines in 2001, which then cut flights to St. Louis by more than half. In 1980, the area had twenty-two Fortune 500 companies. Today, there are nine. One of them, the health care firm Express Scripts, is in the process of being acquired by Cigna, a Fortune 500 health insurance company based in Connecticut.

In other words, any hope for a path to responsible progressive governance in America without radical revolutionary constitutional change lies through reorienting the economy toward a more equitable distribution of gains, secured in part from anti-monopolistic practices. The alternative is a retreat to an unacceptable defeatism.

It’s certainly worth a try to secure a clear legislative majority without giving ground on social justice. And even if it fails to win over an adequate number of working-class white voters in the heartland, it’s still the right thing to do regardless.