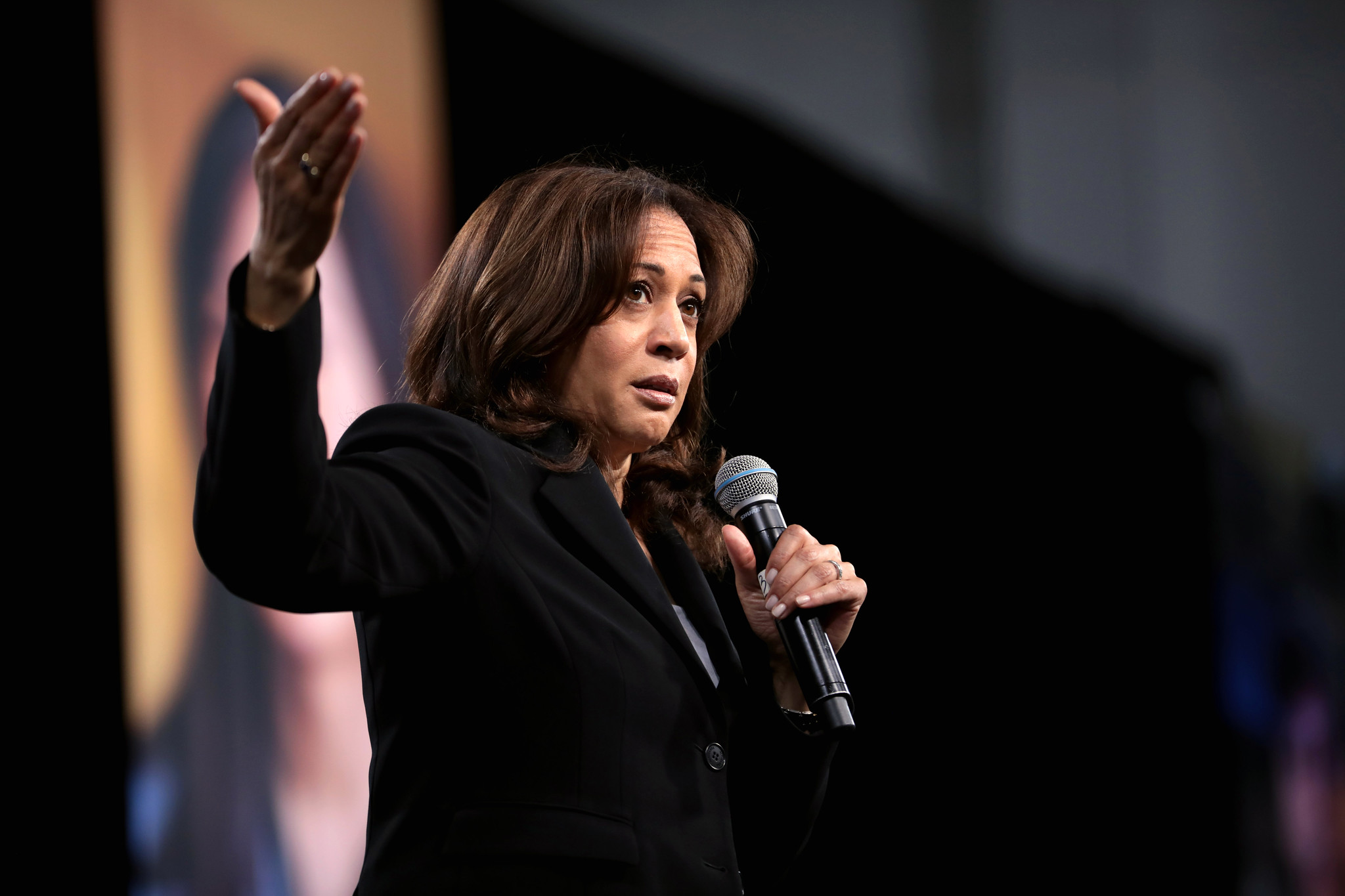

Like any skilled prosecutor, Kamala Harris knows how to present evidence in a favorable light. She spent her childhood in Berkeley, California but launched her presidential campaign from her birthplace of Oakland, a backdrop that better supports her narrative as a fighter for the people. She courts progressives by portraying herself as a criminal justice reformer, citing her record as California Attorney General. She positions herself as a pragmatist, arguing that while other Democrats have theoretical, ideological debates, she is focused on taking action to improve the lives of American families. It all supports her closing argument that she is the best candidate to “prosecute the case against four more years of Donald Trump.”

But she isn’t.

Harris’s more complete history tells a different story—one of a candidate with limited experience, a controversial track record, frequent reversals on policy issues, and election results that don’t inspire confidence. Because she rose to national prominence so quickly, it’s easy to forget that Harris is still not halfway through her first term in the Senate. She was inaugurated in January 2017. Eighteen months later, she was already spending more on Facebook ads to harvest emails from potential supporters than any other Democratic presidential contender, seemingly preparing to run for President shortly after or becoming a Senator. During her tenure she has introduced many bills, but has been the primary sponsor on just four successful ones, none of them major.

Harris’s lack of legislative experience is not, in itself, an insurmountable liability. Barack Obama successfully ran for president in the middle of his first Senate term and served admirably once elected. But Obama’s limited track record was defined primarily by his principled opposition to the Iraq War. Harris’s record is defined by controversial decisions and politically convenient turnarounds.

As California attorney general, she and her staff fought to uphold wrongful convictions and prevent potentially exculpatory evidence from coming to light (as has been well documented). She supports marijuana legalization now, but she refused to express an opinion in 2014 or 2016. In 2017, she introduced a bill to reform the cash bail system, but as San Francisco District Attorney, she supported raising cash bail costs. She has oscillated when asked about the role private insurance should have in our health care system.

Harris is quick to tout her most notable achievements including, Back on Track, the 2005 program aimed at reducing recidivism; requiring police officers under her direct supervision to wear body cameras; and instituting racial bias training for officers in 2015—all of which are commendable. But she has not admitted to, nor offered convincing answers for, her less laudable conduct, probably because she can’t. What good explanation is there for trying to keep an innocent man in prison?

Some commentators, like Bill Maher, have argued that we should be less concerned about how politicians like Harris evolve than where they end up. But Harris has changed positions so often that it’s difficult to know when she has finally made up her mind. To voters, her switches may look more like a product of calculation than evolution. In a field that includes more experienced candidates with more consistent track records like Amy Klobuchar, Cory Booker, and Elizabeth Warren, it would be risky for Democrats to nominate someone who has flip-flopped as much as Harris.

There is little evidence that Harris is the right candidate to help Democrats reclaim key swing states like Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania. Early polling can be unreliable, but Harris has consistently fared the worst of the four leading candidates in head-to-head match-ups against Trump. More importantly, her electoral history does not portend success in the Midwest. In Harris’s first statewide race, for Attorney General in 2010, she eked out a victory against Republican Steve Cooley by less than one percent—in California. She fared much better overall in 2014 as an incumbent against Republican Ron Gold, but she also lost eight of the counties Hillary Clinton won in 2016. Do Democrats really want to pin their hopes on a candidate who underperformed Hillary?

Harris has many virtues—she is a skilled inquisitor, a commanding debater, and she has star power. After her attack on Joe Biden during the first Democratic primary debate, it was easy to imagine her taking the fight to Donald Trump if given the chance. She has inspired a devoted following called the #KHive that swarms social media to promote her candidacy. They praise her as a fighter, a storyteller, and a charismatic woman of color.

But in a deep Democratic field, other candidates surpass Harris where it counts the most. Warren has more transformative plans. Klobuchar has a better record of getting things done. Sanders and Warren have stronger progressive credentials. Biden and Klobuchar seem to have more appeal in swing states. Buttigieg has a more measured Obama-like temperament. More than half a dozen senators and governors running are more experienced than Harris. Perhaps against a former reality star, Harris’s star power should count for more, but her appeal may be too limited to attract broad support.

Indeed, as Harris’s star has risen, so has criticism of her approach. Whereas Harris’s supporters delighted in her attack on Biden for his record on busing, many Democrats saw it as a cheap shot to attack Biden for having a position on forced busing in the 1970s that is eerily similar to Harris’s position today. When pressed after the debate, Harris admitted that she doesn’t currently support federally mandated busing, saying that busing should be “in the toolbox of what … should be considered by a school district.” In other words, she criticized Biden for not supporting something that she doesn’t support either. Harris sells herself as a girl from Oakland who grew up to fight powerful interests, but Politico revealed that Harris relied on San Francisco elites and cushy appointments from her then boyfriend, former San Francisco mayor Willie Brown, to power her political rise.

Harris’s emphasis on identity politics is similarly risky. She’s on the opposite side of the spectrum from Trump, but like him, she uses race as a wedge issue. Her attack on Biden—and by extension, people like him—served her campaign’s needs. But making older white Americans feel guilty for opposing forced busing is not a recipe for winning in swing states. Democrats need a nominee who will make Obama/Trump voters, many of whom are white, feel welcomed back.

Perhaps most importantly, Democrats need a candidate who provides strong, favorable contrasts to Donald Trump: a sincere, dedicated public servant with a record of fighting for the working class who unites Americans by appealing to their better nature. Harris, of course, embodies those qualities more than Trump ever could. But if she is the nominee, she will be susceptible to many of the same attacks Hillary experienced. She will be easily portrayed as a shape-shifting liberal, bankrolled by the rich, too focused on ascending the political ladder—attacks from which someone like Klobuchar or Warren would be largely immune.

It’s a cliché, but the 2020 election is historically important and Democrats need to get it right. The stakes are simply too high to rely on a largely untested candidate with lackluster election results in red and purple districts. They need to back an experienced nominee with a consistent record who can persuade swing voters. With many strong candidates to choose from, Kamala Harris is a risk Democrats shouldn’t take.