The U.S. deported approximately 25 Cambodian immigrants on Wednesday—all but one came to the United States legally as refugees and have lived there for decades—according to a Cambodia-based nonprofit dedicated to resettling deportees. The cohort will be the first Cambodians deported in 2020, continuing the Trump-era surge in deportations of Vietnam War refugees.

The deportees, all men between the ages of 33 and 60, arrived in the Cambodian capital of Phnom Penh on January 15, according to Bill Herod, the founder of the Khmer Vulnerability Aid Organization (KVAO), a nonprofit that works to integrate Cambodian deportees into the country. An Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) spokesperson, Mary Houtmann, confirmed the Cambodia removal flight.

All of the individuals expelled have committed some crime that invalidated their permanent residency, Herod told me, making them eligible for deportation. But many of them have never before stepped foot in Cambodia; they were either born in Philippines or Thailand refugee camps to parents fleeing Khmer Rouge massacres and the Vietnamese occupation of Cambodia that followed. Nevertheless, the Trump administration has increased the deportation of them, all the while substantially limiting legal immigration and asylum claims.

As I reported last year, the Trump White House has also repeatedly pressured Vietnam to take back refugees with criminal convictions who arrived in the United States before July 1995 and had, under an earlier agreement between the U.S. and Vietnam, been explicitly deemed undeportable. According to I.C.E. reports, about 38 Vietnamese were deported per year from 2014 through 2016, the last few years of President Barack Obama’s second term. Under Trump, that annual average has increased to 91.

And while Cambodian removals began in 2002 under a bilateral agreement signed by both countries—and continued largely unabated under both presidents George W. Bush and Barack Obama—the Trump administration has ratcheted up the rate of deportation. Under Trump, an average of 68 Cambodian refugees have been removed per year (not including this January group). Under Bush and Obama, the average was about 26 and 43 per year, respectively. The U.S. has deported 742 Cambodian refugees since 2002, according to KVAO’s records, excluding the latest cohort.

These refugees, who lived in the U.S. legally and obtained green cards, were convicted on a charge of an aggravated felony, a classification expanded by a 1996 crime bill signed into law by then-President Bill Clinton. Those offenses, which invalidate one’s green card, include not only serious crimes like sexual assault and murder, but also any “crime of violence” (a vague standard that has enabled the overturning of some deportations) and any crime of theft or burglary for which the term of imprisonment is at least one year. In some cases, they do not include violent crime.

Immigration law can allow for the compounding of two misdemeanors—such as petty theft and personal marijuana possession—into an aggravated felony that would also invalidate one’s green card, as was the case with a few Cambodian deportees I met in Phnom Penh last year.

Once deported, they often struggle to assimilate. Some do not speak Khmer, Cambodia’s language, and most find the culture alien. Cambodians, meanwhile, view them as troublemaking barang—foreigners. “Here,” one deportee told me in Phnom Penh, “if they see you’re a returnee, they don’t like you that much.”

Some are even less fortunate. Sophorn San came to the U.S. as a four-year-old and grew up in Providence, Rhode Island. In 2010, at age 19, he pleaded guilty to possession of a handgun without a permit and was sentenced to six months in prison. The crime was an aggravated felony, making him eligible for deportation. But San was represented by a public attorney seemingly unaware of this; the attorney advised that he take the plea deal. Three months after San was granted parole in February 2016, I.C.E. detained him. By December 2018, he was on a plane to Cambodia.

He was 27, and the youngest member of this December contingent, a fact for which I remember the others teasing him. In early January 2019, I met San and a few of these other fresh deportees on the outskirts of Phnom Penh, where we dined on kuy teav, Cambodia’s traditional noodle soup. They ordered in an Americanized Khmer that elicited giggles and raised eyebrows from the young waitresses. Two months later, San was gone. He died in a gruesome motorcycle crash—an all-too-common occurrence in Cambodia, where road crashes are the leading cause of death.

Stories like his are not that uncommon: Since 2002, forty deportees have died, at least six by suicide, according to Herod. “The death by deportation label could easily be applied to those who have been diagnosed with severe mental health or physical conditions before deportation,” he told me, explaining that KVAO is now increasingly receiving high-risk individuals with debilitating diseases and disabilities. “The psychological shock of deportation is more a factor in some of these deaths than the quality of Cambodian health care,” he added. Indeed, six Cambodian refugees have died in the last two months.

Meanwhile, since Trump took office, I.C.E. has raided Cambodian communities in the U.S. approximately every four months, according to Kevin Lo, an attorney at legal aid group Asian Americans Advancing Justice—Asian Law Caucus. Officials from the United States Embassy in Phnom Penh did not respond to requests for comment.

The Cambodian government initially resisted the Trump administration’s attempted deportation increase in 2017. Then, the White House responded by imposing visa sanctions on some high-ranking government officials and their families. The American and Cambodian governments eventually reached an agreement to resume deportations in February 2018, and Cambodia has since accepted its supposed nationals. Now, roughly 2,000 Cambodians are subject to deportation from the U.S.

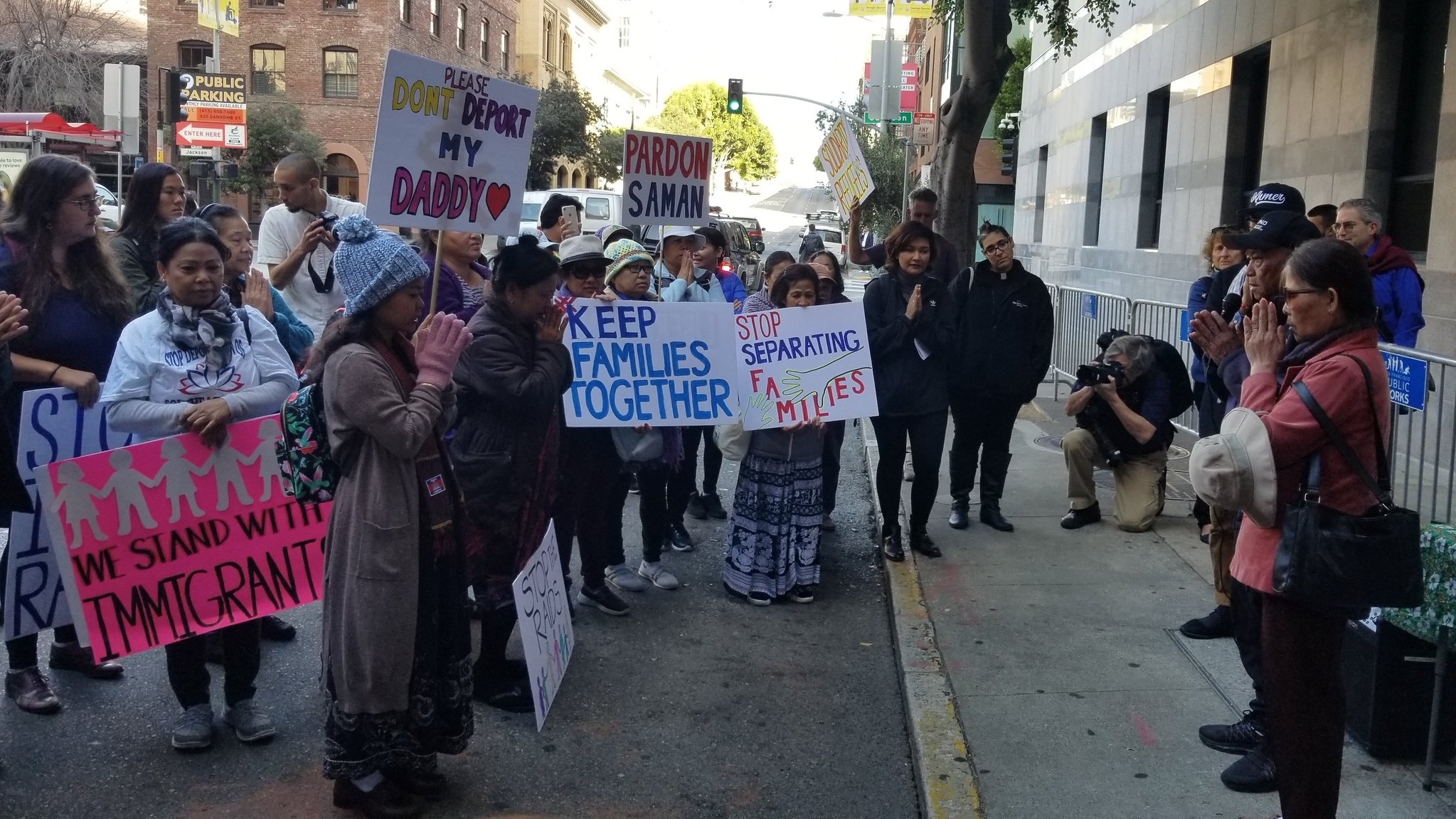

Rights groups are critical of these removals, because almost all of those targeted for deportation came to the United States as refugees and will now be separated from their families who remain there. These groups also argue that these deportations are the last step in a cycle of American failure: The United States secretly bombarded Cambodia during the Vietnam War in operations that many credit with enabling the genocidal Khmer Rouge’s rise to power. After accepting Cambodians (and other Southeast Asians) as refugees, the U.S. failed to provide them with adequate support, priming them for poverty and criminality, the latter of which eventually renders them eligible for deportation.

That might help explain why the Cambodian community is one of the poorest in the United States. Post-traumatic stress disorder also remains endemic among the population. But for now, their deportations will continue.

“I.C.E. is wiping out a generation of Cambodian refugees who mostly came to the United States as infants,” said Lo. “It is heartbreaking that parents and grandparents who survived genocide to bring their children to safety are now losing them to deportation in their old age.”