I have thought for two decades that, if I ever get in trouble, Jamie Raskin is the lawyer I would want.

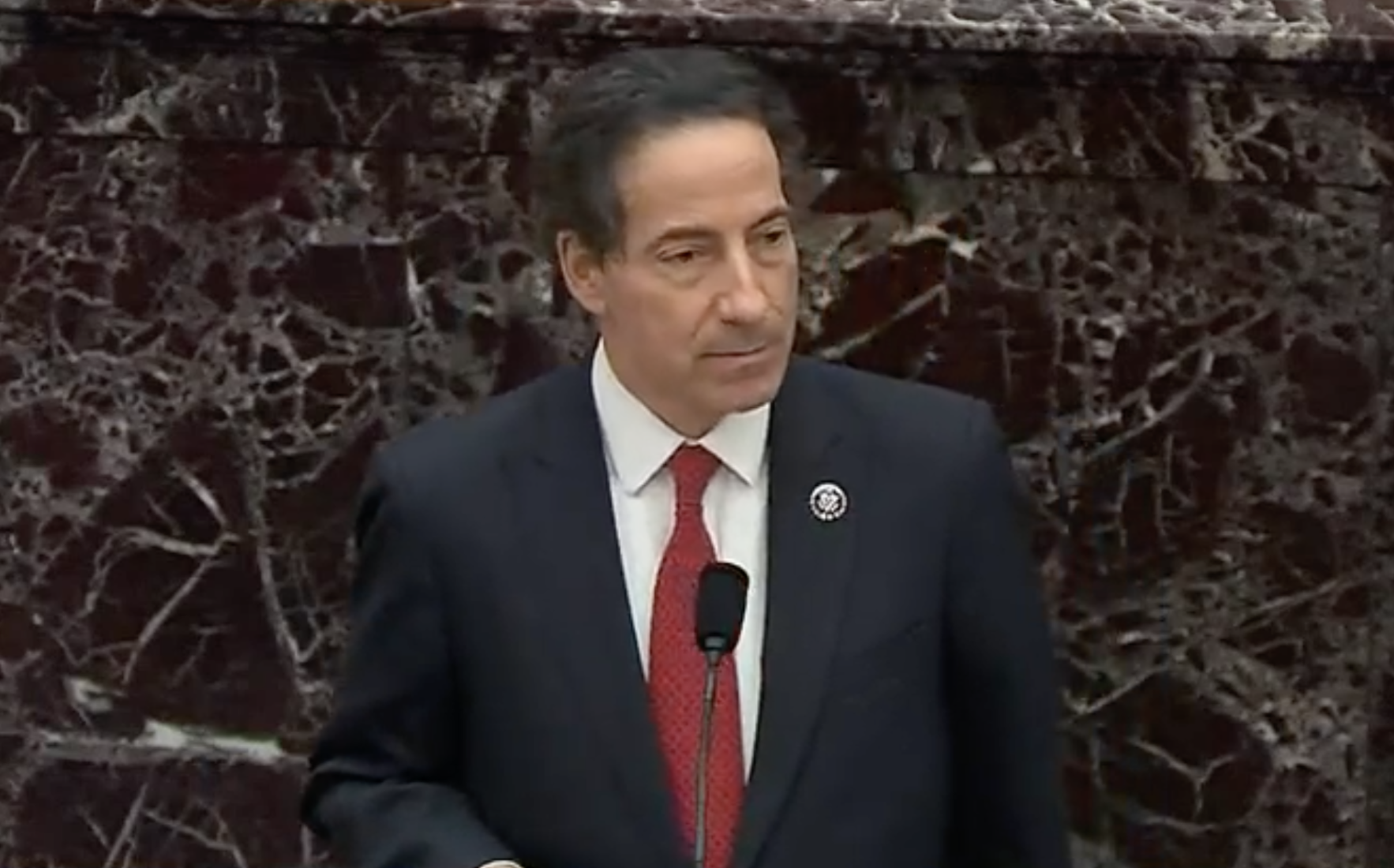

Raskin, a longtime law professor and now a Congressman from Maryland, would probably have out-lawyered almost any defense team arrayed against him at the second impeachment trial of Donald Trump. But could we have imagined that the former president’s defense team would mount such a pitiful case on his behalf? Given his previous counsel, from Rudy Giuliani to traffic ticket litigator Jenna Ellis to QAnon-happy Sidney Powell, maybe yes.

Begin with the House case: The president spent weeks trying to convince the nation that the 2020 election had been stolen and that only a ‘fight” could “stop the steal.” He begged his followers to come to Washington on January 6 for an event that he said “will be wild!” Once they were assembled, he told them that he would lead them himself to the Capitol, where they would “fight like hell.”

Regardless of the promise, Trump went back to the White House and settled down in front of his TV. There he remained, apparently chortling, while the mob he had sent down Pennsylvania Avenue breached the Capitol, brutalized Capitol Police, invaded the two congressional chambers, and seemed eager to assault and even murder members of Congress—and, for that matter, Trump’s own hitherto loyal Vice President, Mike Pence. Later in the afternoon, he urged his disciples to be peaceful, but at no point that afternoon did Trump denounce the rioters/terrorists, and at no point did he deploy federal power to guard the Capitol. After the insurgents were pushed out, he tweeted a video telling them, “We love you.”

Raskin laid out these events to the Senate and the nation, accompanied by a powerful video of the storming of the Capitol. Rep. Joe Neguse (D-CO) then offered a rebuttal to the argument that the Senate could not try Trump because he had left office following his impeachment. (The majority of scholars have concluded that argument is wrong.) Rep. David Cicilline (D-RI), the former mayor of Providence, then summed up the gravity of the offense that, Democrats contend, demands that the Senate disqualify Trump from future office: “President Trump was not impeached because he used words that the House decided are forbidden or unpopular. He was impeached for inciting armed violence against the government of the United States.”

Then Raskin closed, explaining the impact of the attack on the Capitol on him and his family. He had invited his daughter and son-in-law to be present to witness the certification of the election—as much, it seems, to distract him and them from the funeral the day before of Raskin’s beloved son Tommy who had committed suicide. While Raskin was hustled to a different location, they were locked in the majority leader’s office—and, like most others, trapped by the mob, anticipating imminent violent death.

When they were reunited, Raskin said to his daughter that the next time she came to the Capitol would not be so bad. “I don’t want to come back to the Capitol,” she said.

At this point, Raskin’s voice broke.

That moment is what anyone who watched will remember, not just during the trial but for years to come. Aristotle wrote in Rhetoric that forensic rhetoric had three aspects—the logos, or the validity of what was said; the ethos, or the implication by the speaker that he or she is the kind of person whom the listener should listen to; and the pathos, or the emotional content of the speech and of the issue it concerns.

Raskin crushed all three.

That left an unenviable task to former Pennsylvania acting attorney general Bruce Castor. Castor, an accomplished prosecutor, who completely bobbled it, uttering a virtually incomprehensible string of words in which he shared his memories of listening to the late Sen. Everett Dirksen (R-IL) on a record in his parents’ house (he stopped to explain what an old-style vinyl record was; I suspect that he should have explained to the younger Senators who Everett Dirksen was). He mentioned that he personally knows the two Senators from Pennsylvania, then veered to Nebraska, issuing a warning to Sen. Ben Sasse that the Nebraska Supreme Court would not approve of his criticism of Trump: “Nebraska is quite a judicial thinking place.” Castor reminded the Senators that the Constitution provides that “Congress shall make no law abridging all these things.”

Then he sought to terrify the Democrats: If Trump is convicted, then when Republicans take over Congress, they may pay Democrats back by savagely impeaching none other than … former Attorney General Eric Holder for his role in a long-forgotten scandal called “Fast & Furious.”

Like “for God, for Country, and for Yale,” this threat was a crashing anticlimax. And I suspect a few of the younger Senators needed to be reminded who Holder was as well.

There is a case for Trump’s acquittal that doesn’t involve loopy references to Eric Holder. I don’t find that case convincing, but any good lawyer would admit it exists. Indeed, almost any half-decent lawyer could make it.

Castor, as it turns out, is the exception to that rule. Indeed, so inept was his presentation that I wondered whether (as he suggested) the Trump lawyers had actually prepared for a different set of issues altogether and that his co-counsel, defense lawyer David Schoen, had pushed him onto the stage to vamp while Schoen hastily scribbled an actual response to the House managers’ opening. When Schoen finally arose, he did manage to focus on the one issue that his Republican audience wanted to hear about—that Trump cannot be tried now that he is no longer president. That’s also not a killer argument, but it is, in fact, an argument. It also offers Republicans an excuse for voting against conviction while insisting that they don’t support hanging Mike Pence or killing Capitol Police. It’s an intricate argument, and its comprehensibility wasn’t improved by being rapidly read from a piece of paper. Schoen did manage to mention that he had personally spoken with former Whitewater Independent Counsel Kenneth Starr. Starr, it turns out, agrees with him. Some Democrats, he noted, had wanted to push Trump out of office long before the assault on the Capitol.

Schoen closed by reading from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s “The Building of the Ship.” That poem, written during the Civil War era, contains among the most powerful lines in all of American civic poetry:

Thou, too, sail on, O Ship of State!

Sail on, O Union, strong and great!

Humanity with all its fears,

With all the hopes of future years,

Is hanging breathless on thy fate!

Schoen’s reading was toneless and rushed, as if he were ashamed to invoke those words on behalf of a president who, more than any other in our history, had tried to capsize the ship of state rather than give up the helm.

Offered the chance to rebut, Raskin declined. As I said, he is a great lawyer.