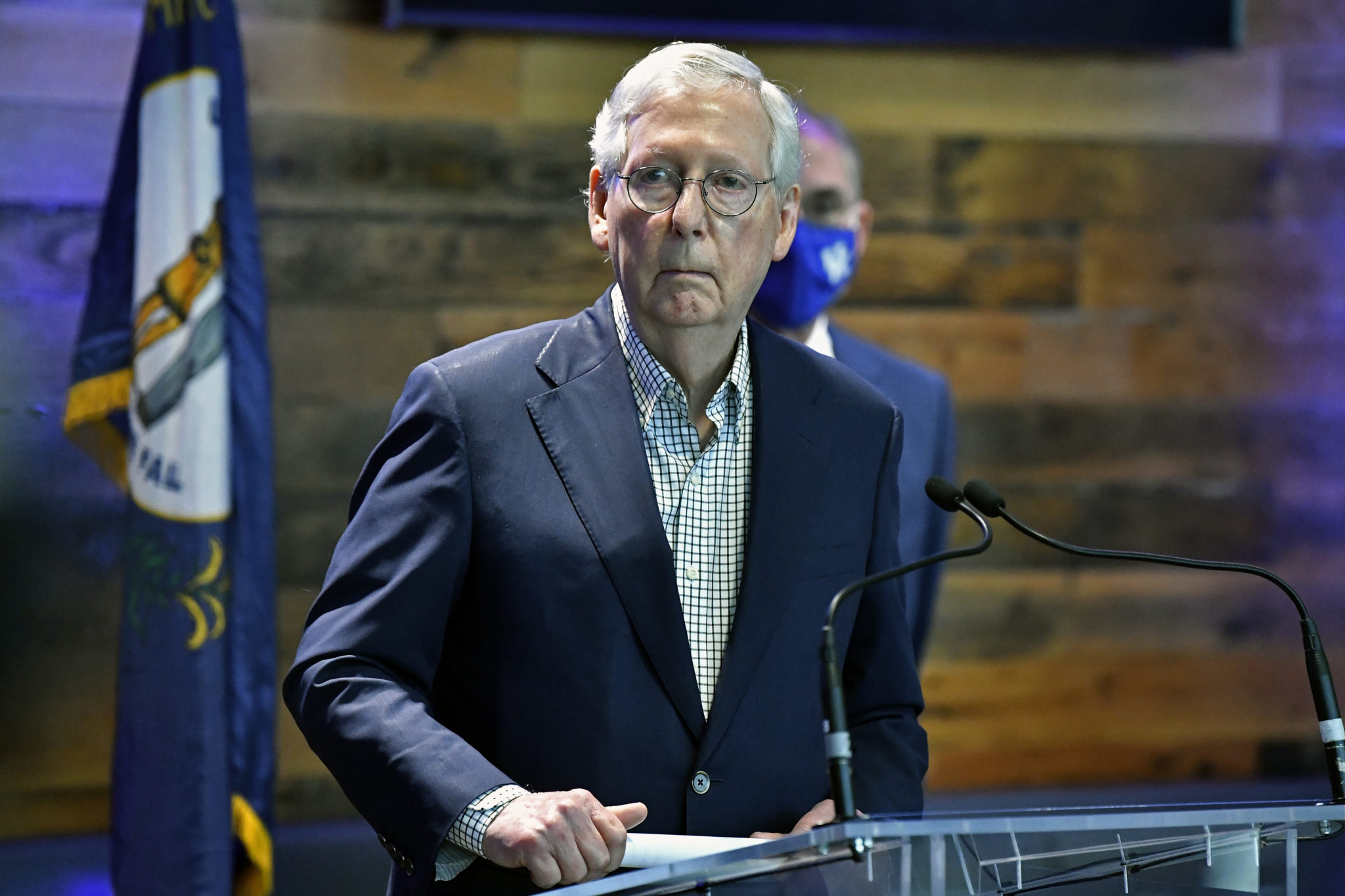

Gentle reader, do you sometimes idly imagine how pleasant life would be if Senator Mitch McConnell (R-Ky) decided to enjoy a well-earned retirement in some serene and sunny spot? It doesn’t seem likely—but there is one sign that the Grim Reaper may be contemplating an early exit from the Senate. Last month, he helped Kentucky state legislators devise and pass (over a gubernatorial veto) a change in Kentucky’s law governing Senate appointments. Now, if McConnell leaves office in the next two years, his seat will remain firmly in Republican hands.

Kentucky’s governor, Andy Beshear, is a Democrat. Until a few weeks ago, Kentucky law provided that, if McConnell were to leave office, Beshear would appoint a temporary replacement as governors do in most states when an incumbent U.S. Senator leaves before the end of their term. That was enough to throw the Republican legislators into a state of apoplexy: Beshear might appoint a Democrat, strengthening Democratic control in the Senate.

To forestall that possibility, the Republican-dominated legislature passed a new Senate-appointment statute, S.B. 228. Under the new statute, if a Senate seat becomes vacant, the governor would be required to choose a replacement senator from a list of three candidates supplied by the executive committee of the outgoing Senator’s party.

Though the fight over S.B. 228 was primarily a matter of bare-knuckle politics, it had a constitutional dimension. In his veto message, Beshear said the bill “improperly and unconstitutionally restricts the Governor’s power to fill vacancies in the United States Senate. … The purpose of the Seventeenth Amendment…was to remove the power to select United States Senators from political party bosses.”

Beshear has history on his side: Direct election of Senators was written into the Constitution only after one of the most remarkable popular mobilizations in American history—a two-decade-long revolt against the rank corruption of state legislatures. Now largely forgotten, in the fight for direct election, the people, disgusted by the orgy of corruption and partisanship that marked Senate elections by the legislature during and after the Gilded Age, did the near-impossible, by forcing an entrenched political class to vote for its own dissolution.

The 17th Amendment, accordingly, gets very little love from the heirs of Gilded Age politics. Washington Post columnist George Will has for years lamented the end of legislatures electing Senators, under which “the nation got the Great Triumvirate (Henry Clay, Daniel Webster and John Calhoun) and thrived.” The Tea Party movement embraced a demand to “Repeal the 17th,” arguing that, in the words of one advocate, it would end “federal deficit spending, inappropriate federal mandates, and federal control over a number of state institutions.” Former Texas Gov. Rick Perry dismissed the 17th Amendment as “a fit of populist rage” wedged into the Constitution by an insensate populace. More recently, Nebraska Sen. Ben Sasse, without apparent irony, published an op-ed in the Wall Street Journal, urging the nation to “Make the Senate Great Again.” Today’s politics are “polarized and national,” he said. ‘That would change if state legislatures had direct control over who serves in the Senate.”

These arguments are so thin that I assume even their proponents don’t believe them. Will’s rhapsody to the “Great Triumvirate” only makes sense if we define “thrive” as “collapse into Civil War.” Clay, Webster, and Calhoun guaranteed that slavery won the important antebellum battles until the Republic fractured. That legislatively appointed Senators would miraculously vote against deficit spending is a complete non sequitur and might come as a surprise to anyone who has been to Trenton or Frankfort. Perry’s grasp of history is, shall we say, shaky—the amendment isn’t a tattoo acquired during a drunken spree, but a decision insisted on by an outraged public. As for Sasse, his argument isn’t wrong; it just isn’t really an argument at all.

At any rate, the 17th Amendment isn’t going anywhere, so it may be time for the nation at large to understand it. Most people—even those who follow politics—think it provides that (1) Senators must be elected by the people and (2) governors may appoint replacements to serve out senatorial terms vacated by death or resignation of a senator, without having to run them by some party committee.

The reality is a good deal more complex. The original method of Senate election was by each state’s legislature. That created a problem: how should unexpected vacancies be filled? State legislatures, of course, are not always in session—and in the 18th Century, calling a special session would be a cumbersome and expensive process, involving days of travel for some members to get to Pierre or Carson City. Accordingly, the framers provided that “if vacancies happen by resignation or otherwise, during the recess of the legislature of any state, the executive thereof may make temporary appointments until the next meeting of the legislature, which shall then fill such vacancies.”

But after 1913, senators from each state are to be elected by “by the people thereof.” The legislature is ostentatiously given no role in selecting senators. If a vacancy arises, the Amendment says, “the executive authority of such state shall issue writs of election”—the same language that requires a special election for a vacant House seat. So, the normal procedure would be for the governor to schedule an election without consulting anyone. However, in a “proviso,” the amendment gives states an option: the legislature “may empower the executive thereof to make temporary appointments until the people fill the vacancies by election as the legislature may direct.”

In other words, immediate replacement by popular election is the norm. But if the legislature chooses, it can allow the governor to make temporary appointments. It can also set in advance a method of scheduling special elections. That’s it.

Seventeenth Amendment caselaw is a bit thin. In 1969, a group of New York voters challenged a state law that allowed a “temporary” appointee by Gov. Nelson Rockefeller to serve the entire remaining term of assassinated Senator Robert Kennedy. A district court rejected the claim, and the Supreme Court affirmed without opinion or explanation. Then in 2010, a group of Illinois voters challenged Gov. Rod Blagojevich’s appointment of Roland Burris to fill the remainder of President Barack Obama’s Senate term. That wasn’t a “temporary appointment,” they argued since it took up the entire rest of the term. The Seventh Circuit agreed. By the time it did, however, the victory was largely symbolic—on Election Day 2012, Illinois held two Senatorial elections, one for the next full term and the other for the month remaining on Obama’s term. (Disclosure: I did some consulting on that case, Judge v. Quinn.)

Other 17th Amendment cases have not gone as well for the challengers. In the 2018 case of Hamamoto v. Ige, two Hawaii voters challenged a state law like Kentucky’s: it required the governor to make a “temporary appointment” from candidates screened by a partisan panel. That case was dismissed as moot after a special election filled the seat vacated by the death of Sen. Daniel Inouye. Then in 2020, the Ninth Circuit dismissed a challenge by Arizona voters to the appointment of Martha McSally for the 27 months remaining on the term of Sen. John McCain without any special election. They also argued that state law requiring the appointee to be of the same party as the departed senator violated the 17th Amendment. The court declined to decide the issue since, it pointed out, Arizona Gov. Doug Ducey could appoint McSally even without the party requirement.

So, the law on partisan appointment limits is unclear. No matter the evasions by judges, these requirements stick in my craw. If the legislature is entitled only to “empower” the governor to make a “temporary appointment,” where does it get its own authority to limit the governor’s choice to one political party?

But, like Hawaii’s, the Kentucky law goes further—it “empowers” the governor to appoint one of three nominees selected by officials of a political party. That is, the selection is made by partisan figures not elected by the voters. Where do legislators get the power to transfer the governor’s authority to these outsiders?

Could the legislature require the governor to appoint someone chosen by the legislature? The question answers itself. The point of the amendment is to take this decision away from legislators. Could the legislature then “empower” the governor to choose the single candidate selected by the party committee? The idea is nonsensical; it doesn’t become valid simply because the governor is given a “choice” of three individuals selected by a political party.

Will a court settle this dispute? Probably not. There is no “case” until either McConnell or Sen. Rand Paul leaves a seat vacancy. If Beshear is still in office, he could bring a challenge at that time. But let’s remember that McConnell has spent the last four years playing Santa Claus to Republican judicial nominees. He can expect them to show some gratitude.

But I can dream. For a Constitutional Law geek, few things are more satisfying than seeing politicians tripped up by obscure constitutional clauses. When the Republican House majority in 2011 threatened to force the U.S. into financial default, the nation got a crash course in Section Four of the Fourteenth Amendment, which provides that “the validity of the public debt of the United States . . . shall not be questioned.” I doubt that President Donald Trump had ever heard of the Compensation Clause, Article I, Sec 1, cl 7, and the Foreign Emoluments Clause, Article I, Section 9, Cl 8 until he was sworn in; but the “emoluments” cases, filed three days after his inauguration, bedeviled his legal team until he left office, at which point they were dismissed as moot. Barack Obama’s appointments to the National Labor Relations Board were invalidated under the Recess Appointment Clause. The House Pistol-Packing Caucus, which claims the right to ignore the metal detectors outside the chamber, may come to grief because they have misread the “Privilege of Arrest” Clause, which does not immunize House members from arrest on criminal charges. And a measure currently pending in the House would use Section Three of the Fourteenth Amendment (barring from office any former federal official who engages in “insurrection or rebellion”) to stymie Trump’s expected 2024 presidential bid.

The 17th Amendment, I think, is more important than some of the provisions above. It embodies a modern vision of American citizens as active participants in their own self-government. Politicians and judges tend to see the Constitution as empowering and protecting them by barring lawsuits against prosecutors, police, judges, or high government officials. The emerging American right apparently sees it as exempting them from any law that aims at the common good. But the 17th Amendment affirms that in a democratic republic, the people—not jacks in office or goons with guns—rule. American freedom is the freedom that comes from active citizenship. It’s ironic that those who are quick to decry government and champion individual choice are now the most likely to hand over electoral power to politicians.

So it would do my heart good to see the latest maneuver by Sen. Mitch McConnell and his friends in the Kentucky Republican Party come to grief because of this vital progressive victory.

Of course, McConnell is the Vito Corleone of conservative jurists; he has done a service to so many new federal judges, who may render him a service in return. But still, wouldn’t you like to see Democrats challenge Kentucky’s Republican law and deliver another crash course in the GOP’s contempt for both voters and the Constitution? The odds against it are long, but we at the Monthly have laughed at longer odds. For nearly four decades, after all, our founder wrote in every issue a column titled “Tilting at Windmills.”