For nearly 60 years, the actual malice rule has been a driving force in American libel law, protecting the media and others who criticize public conduct. This protects them from often frivolous lawsuits. The rule—which is substantively different from traditional malice, that is, hatred or ill will—limits defamation claims made by public officials and public figures. In order to collect damages, these plaintiffs must prove that the publisher of allegedly defamatory material was lying when the material was published—or was recklessly indifferent to truth or falsity. The rule is so much a part of the fabric of libel law that the Supreme Court has not dealt substantively with it in over 30 years.

But there are judicial grumblings that the Court may need to reconsider the rule. Two judges (one of them a Supreme Court justice) have caused a flurry of legal commentary by calling for the reconsideration—and doing so in a context that suggests the press in America is too free. Neither judge makes a sound argument for changing the law but combined with a slew of recent libel actions raising questions about actual malice, the door for possible judicial action has been opened, if only slightly.

The elimination of actual malice would be the most serious attack on free speech in generations, an action that would greatly chill public discourse and could reduce reporting on public affairs to little more than secretarial duty.

The idea of actual malice was borrowed from the common law and state tort law by Justice William J. Brennan Jr. It wasn’t manufactured out of thin air. It became part of constitutional law in the 1964 case of New York Times Co. v. Sullivan. The libel suit was based on a full-page advertisement soliciting funds for the defense of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. The ad was also critical of what it considered bogus arrests of Dr. King for minor infractions. Justice Brennan wrote that the First Amendment absolutely did away with the English crime of seditious libel—meaning statements critical of officials or government in general. In order to fully eject seditious libel from U.S. jurisprudence, Brennan reasoned, critics of public conduct need sturdy protection from libel suits by government officials. That protection was the actual malice rule, which required a public official to prove that an allegedly defamatory statement was published “with knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not.”Later, the Court applied the rule to public figures and to public figures bringing actions for intentional infliction of emotional distress.

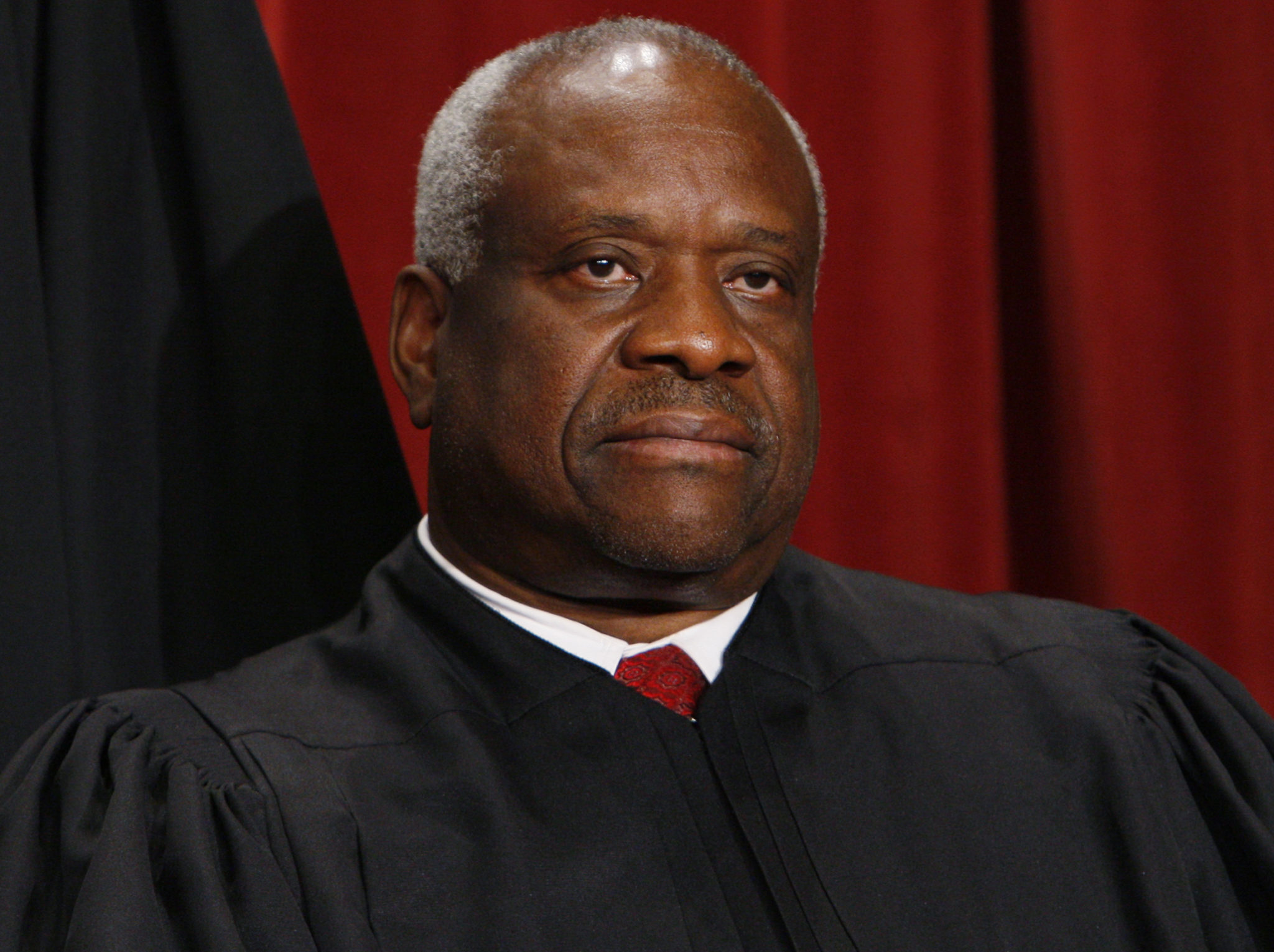

The rule was controversial from the outset, and by the mid-1980s some justices suggested its reconsideration. In 2019, Justice Clarence Thomas called for the Court to reconsider actual malice. His call came in an already controversial case. Katherine McKee, one of more than twenty women who publicly accused entertainer Bill Cosby of rape, sued Cosby for defamation after his attorney called her a liar. The First Circuit Court of Appeals found her to be a public figure and, therefore, required to prove actual malice.

McKee sought relief in the Supreme Court, arguing that she was not a public figure, and that the actual malice rule thus should not apply. The high court refused to hear the case. Thomas concurred in the refusal to take up the factual question of whether she was a public figure, but McKee had not asked the Court to reconsider actual malice. He indicated that he’d favor a challenge to the entire Sullivan rule. Sullivan, he wrote, was “a policy-driven decision[] masquerading as constitutional law. Instead of simply applying the First Amendment as it was understood by the people who ratified it, the Court fashioned its own” federal rules. Justice Thomas referenced the “original meaning” or “original understanding” of the Founders six times as grounds for revisiting the decades-old Sullivan case.

Since Thomas didn’t dissent from the Court’s decision not to hear the case, it’s possible that his jab at Sullivan was bluster, but that’s unlikely. He has also called for greater protection for commercial speech and a reconsideration of the law that allows broadcast stations to be regulated more stringently than print media or the Internet. Neither call gained support from his colleagues on the Court, which makes sense since, for instance, the idea of airwaves as a government good, subject to licensing and government standards, has been with us for decades. Nevertheless this month, Thomas issued a separate opinion in another so-called “shadow docket” case, in which he suggested that the government should require corporation-owned social media platforms like Twitter and Facebook to allow any post by a user, rather than having the First Amendment right to exclude content they find dangerous or objectionable. So much for private enterprise.

Last month, a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia joined Justice Thomas’s plea. In a complicated case involving the sale of oil plots, two Liberian officials sued a watchdog group for implying they had received bribes in order to facilitate the sale. The D.C. Circuit panel found that the officials did not make out a plausible case of actual malice on the part of the watchdog. Judge Laurence Silberman, one of the judiciary’s most prominent conservatives, disagreed with much of the majority opinion, including the interpretation of the evidence. What was newsworthy about his dissenting opinion was the virulence of his attack on the actual malice rule. Sullivan has become “a threat to American democracy,” Silberman wrote. “It must go.”

Silberman’s disdain for the actual malice rule was directly tied to its protection of what he dubbed liberal media who, he wrote, “manufacture[] scandals involving political conservatives.” Finding their bias against the Republican Party shocking, he wrote, “The ideological homogeneity in the media—or in the channels of information distribution—risks repressing certain ideas from the public consciousness just as surely as if access were restricted by the government.” He specifically identified as culprits The Washington Post, The New York Times, and the news sections of The Wall Street Journal. (Silberman approves of the Journal’s editorial stance.) He declared that “a biased press can distort the marketplace. And when the media has proven its [sic] willingness – if not eagerness – to so distort, it is a profound mistake to stand by unjustified legal rules that serve only to enhance the press’ power.”

Silberman’s attack, like Thomas’s, has elements that belie credibility. He spent nine pages of a 23-page dissent criticizing the Sullivan case and four of those nine pages excoriating the media. (The entire majority opinion was only 17 pages long.) The opinion was an exercise in self-righteousness. It is an attack on the 57-year-old Sullivan precedent, one of many such attacks likely to continue due to the flurry of libel actions filed by and against public figures recently. The viability of the actual malice rule may yet reach the Supreme Court and the next time the Justices may bite.

Palin v. New York Times Co. is such a case. Sarah Palin, the former vice-presidential candidate, is suing the newspaper claiming the Times defamed her in an editorial that suggested a website operated by her political action committee may have been incitement for the 2011 shooting in Tucson. In the shooting, an assailant named Jared Lee Loughner killed six and wounded Rep. Gabby Giffords (D-Ariz.) so severely that she eventually resigned her House seat. In a correction, the Times reported that there was no evidence of the connection.

In an opinion that raised eyebrows, the Second Circuit has cleared the way for a trial, which could be held as early as this summer. The court ruled that Palin could satisfy a jury that the newspaper published with actual malice. The court found significant that the editorial included a hyperlink to a Times news story that contradicted the editorial’s main thrust; that editorial page editor James Bennet (a contributing editor at The Washington Monthly) rushed to publish the editorial when he could have taken more time conducting research; and that there may have been a preconceived notion Bennet was unwilling to change, possibly because of animus toward Palin. (Bennet’s brother, Michael, is a U.S. Senator from Colorado, a Democrat, and marked by Republicans as an election target.) Bennet eventually left his post as editorial page editor. (The immediate cause of his dismissal was an inflammatory op-ed by Sen. Tom Cotton (R-AR) calling for the use of Army troops against Black Lives Matter protesters. In his memo, publisher A.G. Sulzberger said that “breakdown in our editing processes” was “not the first we’ve experienced in recent years.”)

In the district court, Palin’s lawyers argued that the actual malice rule should not bar her suit because the doctrine is “peculiar to a bygone era” and obsolete in the age of the Internet. In New York, District Court Judge Jed Rakoff dispatched the argument in short order. “Binding precedent does not. . . come with an expiration date,” he wrote. “To the extent plaintiff believes the actual malice requirement ought to be abolished, she should make that argument to the appropriate court – the Supreme Court.” Given the chance, Palin’s attorneys are likely to do just that

For the case to get to the Supreme Court, however, four justices must vote to take it. Justice Thomas has expressed his desire to reconsider actual malice. He needs three more. One may be Justice Amy Coney Barrett, who clerked for the late Justice Antonin Scalia, who was a leading critic of the Sullivan case.

Two other possibilities are Justices Neil Gorsuch and, intriguingly, Elena Kagan. Gorsuch has expressed support for the actual malice rule but has also indicated that the original rule may have been stretched too far. As a Justice, Kagan has given no indication that she would favor reconsidering the rule—but as a law professor at the University of Chicago, albeit a very different post, she wrote a law journal article and an entry in an encyclopedia of constitutional law in which she criticized the path the rule has taken. She expressed concern that the actual malice doctrine has strayed from its original moorings and has made libel law unnecessarily complex. Sullivan, she wrote, is a “marvel,” but “the Court increasingly lost contact with the case’s premises and principles.” Now the rule “allows grievous reputational injury to occur without monetary compensation or any other effective remedy.” By overprotecting “sensationalist content,” she suggested, the rule may “have facilitated … both the rise of tabloids and the ‘tabloidization’ of the mainstream press.

While four justices might be ready to consider an actual malice case, the current Court does not seem primed to abandon or significantly alter the rule. On the current Court, other than Kagan, only Justice Samuel Alito has written about actual malice rule, and he offered no complaints.

Justices Gorsuch and Kagan might agree to some fiddling to reduce the complexity of libel law, but there is little evidence that they would go further. Justice Kagan, for example, said she favors “a kind of New York Times v. Sullivansort of rule,” providing protection for “people who did nothing to ask for trouble, who didn’t put themselves into the public sphere.” She added, “That’s a real harm, and the legal system should not pretend that it’s not.” She suggested that possibly the rule should apply only to speech on matters of public concern or that its application be based on “the respective power of the speaker and the subject and the relation between the two.”

A coalition of the Court might be willing to doctor the rule, then, but its abandonment or even major surgery is unlikely, for now. Actual malice has been an important part of speech protection for 60 years. It can survive a reconsideration by the current Court. A democracy demands protection for speech of self-governing importance; actual malice provides that protection.