The following is reposted from Jonathan Alter’s Substack newsletter, Old Goats.

Recently, I was reading my late father’s logs and I learned that I first met Andy Young in 1966 when I was eight years old. Dr. Martin Luther King was living in a slum on the West Side of Chicago to draw attention to racial and economic problems in the North. My parents held a fundraiser at our house for King and a Chicago activist named Al Raby.

Young, as usual, was at King’s side, helping raise a little money (less than $1,000, my father later told me) for a civil rights rally at the Chicago Amphitheater. King gave a short version of his I-Have-A-Dream speech in our living room and I got his autograph on my lined notebook paper from school—a prized possession, of course.

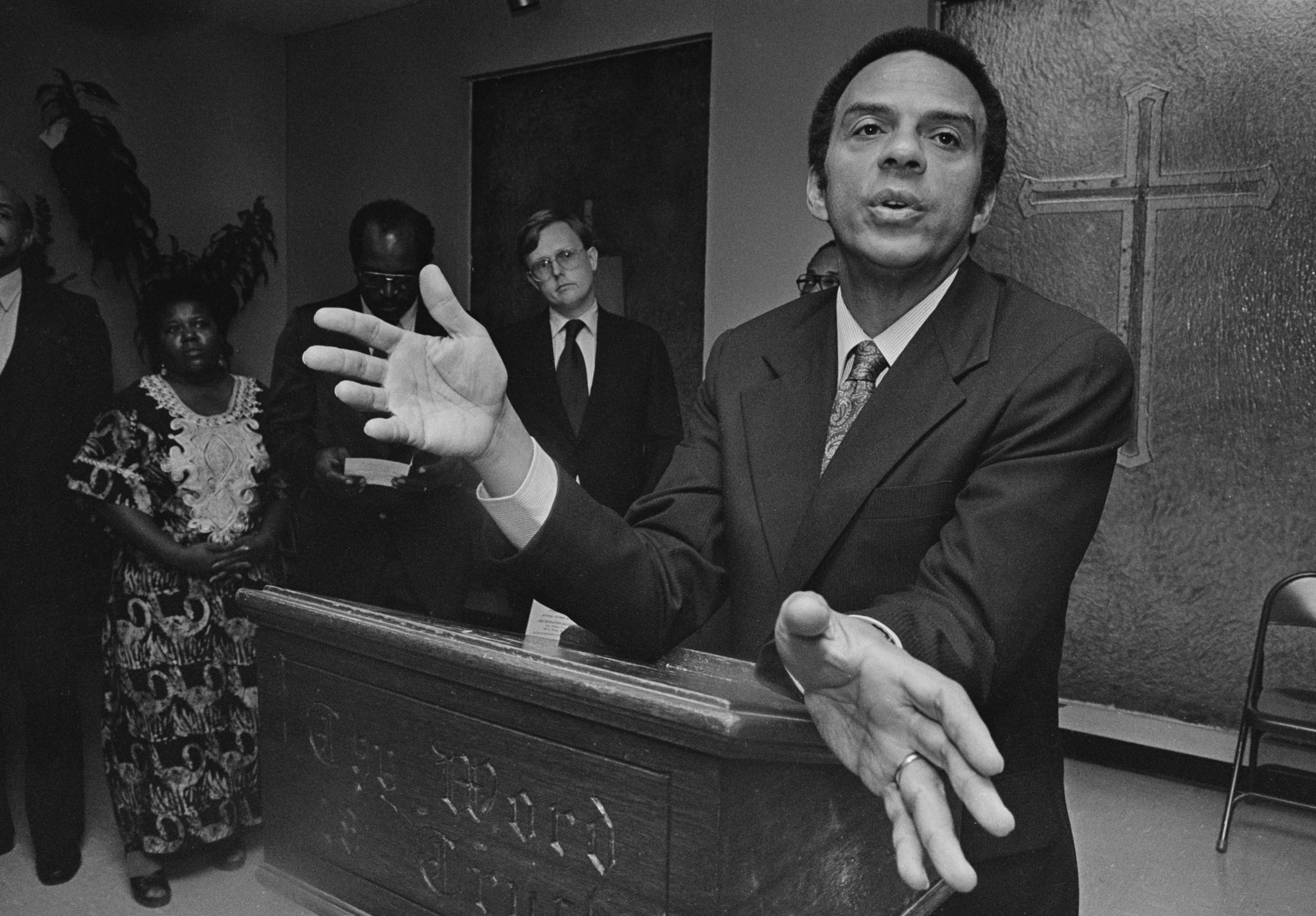

It’s now 55 years later, and I know Andy Young through Jimmy Carter. King’s close confidant and executive director of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference became Georgia’s first black congressman since Reconstruction, Carter’s ambassador to the United Nations, and a well-regarded mayor of Atlanta. He helped me extensively on my Carter biography, and wrote a generous blurb for it. Recently he sat down for an interview.

I’m sorry I missed you at the Carters’ wedding anniversary.

I had to leave early but I was thinking a lot about Jimmy Carter. You can’t understand Carter with a political lens. He’s much more like Martin. Most people want to keep the sacred and the secular separate. With the two of them, they were inextricably bound together. Even at the end [facing a difficult reelection], his decisions were moral. He wouldn’t even think of making a political calculation. Look at his decision to appoint Paul Volcker [as chair of the Fed]. He knew that would hurt him but he did it, anyway.

Carter told me a couple of years ago that if he had to do it over again, he would have fired [Secretary of State] Cy Vance and not you [as U.S. ambassador to the UN] after that controversy over the PLO. I guess it was the people below Vance at State who did you in.

That’s right. You know, I loved that job more than any other I held.

You tell a great what-might-have-been story.

At the first meeting of the Security Council [after Carter became president in 1977], I brought up Iran. An old friend, Graham Leonard, had been teaching in the Quaker schools there and he knew the language and he was back at Harvard and wrote a paper saying that the shah was failing, even if no one knew it yet. He was being undermined in the mosques. Graham said that if Americans were serious about saving Iran, they needed to move it toward a constitutional monarchy. The Agency [CIA] thought that was ridiculous—they were only concerned about the communists.

Imagine if Carter had ignored the CIA and pursued that in 1977. So much would have been different—a hinge of history that swung in a better direction. On the other hand, there was something inexorable about the Iranian Revolution. The shah himself said that if he shot protesters on one street, they’d just pop up on another. He was doomed.

That’s probably right.

Speaking of protest, do you think it’s OK that Black Lives Matter has no high profile leaders?

Not only is it OK, but the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee [SNCC] felt that Martin was too visible—that he could be killed at any time. You can’t replace the preaching of a Martin Luther King or the eloquence of an Abraham Lincoln or Thomas Jefferson. These are the pillars under our democracy. But as Ella Baker said, we also want to broaden the base.

By the way, Black Lives Matter was organized by women. It was the same in Montgomery. None of the men wanted Martin to be the leader. They were preachers struggling for power. It was the women organizing with Rosa Parks, who didn’t even know Martin. You know, self-promoting is the real danger to leadership.

Bob Moses [who died on July 25] understood that, right? He worked at the grassroots, then stepped back.

Bob Moses wouldn’t even say his name out loud at a [voter registration] meeting. But later he’d have thousands of kids doing pre-calculus [through his Algebra Project]. When I was mayor, I sat in on a class but wasn’t smart enough to figure it out. I saw him hold the attention of an entire basketball arena of students. He made them all believe in math.

So many great activists haven’t all been celebrated the way they should, as you explain in your documentary, For All the Saints.

Have you ever seen as much public lying as we have today?

I haven’t. I first got the Boy Scout handbook when I was six years old. Memorized it, though by the time I got to high school I was more interested in Girl Scouts.

How do we deal with the fact that everyone has their own truth?

I guess you ignore it. I can’t even listen to a sentence on Fox that isn’t tainted with falsehood. I don’t know how to deal with it.

We have a good friend who was part of January 6th—a white woman friend of my wife. She got married and her husband got brain cancer and died. You get pretty close to people going through something like that. I’ve not figured out how to approach her now.

Officer Dunn’s testimony before the select committee—the way he was pelted with the N-word.

That doesn’t bother me as much as the suicides [of four Capitol Police officers]—the despair of having to give up on what you really and truly have staked your life on.

But you still sound hopeful.

I think you’re going to see a falling apart of the Senate and the Republican Party. I don’t know how and why, but I can’t imagine an America that is not a democracy. We’re not going to let it happen.

There’s always been something in our movements that caused a breakthrough at the last minute.

[In 1962], we knew we had not prepared in Albany [Georgia]. We did everything wrong but at least we knew we were doing it wrong. We didn’t know how to get discouraged—even when someone would get killed. In Selma, it was Jimmie Lee Jackson.

Dr. William Dinkins, a black doctor who first operated on him, said in Eyes on the Prize that after a week in the hospital Jackson was “well on the road to recovery” with “nothing indicating any danger.” Then white doctors took over, operated on him again for no reason and he died of what Dr. Dinkins described as “an overdose of anesthesia.”

What never got properly reported was that when the young black man who had brought him to the hospital complained about too much ether [anesthesia], they told him, “You get your black ass out of here or you’re next.” If Jimmie Lee Jackson had lived, we probably wouldn’t have had the march.

And we probably wouldn’t have had the Voting Rights Act of 1965. But now it’s under assault. How worried are you?

People have every reason to be deeply concerned. This country is in many ways worse off than it was then. We don’t have a strategy for combating voter subversion. We have to depend on Congress or the Supreme Court and both are long shots now, though I haven’t given up on the Supreme Court.

Why not?

I’m almost 90 and I believe miracles are constant occurrences in our moment. Something always happens. In my grandmother’s terms, “God will always make a way out of no way.” That has consistently happened in my life.

When I was small, my father took me to see a newsreel of Jesse Owens at the 1936 Olympics. He didn’t get intimidated [by Hitler not shaking his hand]. The Nazis left the stadium and he won three more gold medals.

The message was, If you get upset, you will lose the fight. The mantra I was raised on was, Don’t get mad, get smart. When you get mad, the blood runs from your brain to your feet.

But how do you stay cool in a confrontation? When you and Dr. King and Al Raby came to our house in 1966, you were in a confrontation with Mayor Daley.

We weren’t anti-Daley, or anti-Willis [Benjamin Willis, the notorious Chicago schools chief] or even anti-Wallace [George Wallace, segregationist governor of Alabama]. We were for good housing, for good schools, for good health care. Lester Maddox [former segregationist governor of Georgia] and I even became friends later. It was a religious thing. P.W. Botha [the prime minister of apartheid South Africa] was one of the most despicable people I ever met. But I spent nearly an hour with him and didn’t get upset.

I grew up in New Orleans and we had a Nazi Party guy living three blocks down. There was nothing unusual in talking to a right-winger. I was prepared for it and not intimidated by it. Later, it was part of my job. Martin said, “Don’t you know white folks from Birmingham?”

One problem today is that it’s harder to find anybody who knows a lot of white people. We’re getting too many [Black] people who grew up in their own neighborhoods and don’t know how to talk to people outside.

Back to today’s challenge: can Republicans rig the system?

They can, but I still think Liz Cheney may be the Republican nominee.

Things can change fast in politics.

If you have the right attitude.

So good things happen when you stay calm and rational.

Built into our culture is a deep-seated faith in the earth going around the sun. We got two great vaccines in a very short period of time, one developed by a young woman immigrant.

We catch a break when we need it.

Martin would say, “God is still on the throne.” Ralph [Abernathy] liked to say, “I don’t know what the future holds, but I know who holds the future.” That’s the kind of thing we’d hear two or three times a week. Or [quoting Einstein}: “Coincidence is God’s way of remaining anonymous.”

It was too late for Emmet Till. The witnesses weren’t believed. “Truth forever on the scaffold. Wrong forever on the throne.” We’d use that line [from James Russell Lowell during the debate over slavery] all the time.

Followed by “Truth crushed to earth shall rise again.”

We’ve never had a victory nearly as complete as the conviction in George Floyd’s murder. It was because a 17-year-old girl kept her cell phone camera running for ten minutes.

Could the cell phone be changing things in ways we’re just beginning to understand?

It already has. [After Floyd’s murder], we [Young’s generation of activists] couldn’t have gotten a demonstration in six months. Black Lives Matter did it in six minutes because of social media. Within 24 hours, they were demonstrating in New Zealand.

Thanks, Ambassador. I always feel better after talking to you.