Terry Dolan had two funerals. The first, a grand affair at a Catholic monastery that drew hundreds of his right-wing friends, was an elaborate lie of omission. It was true, as mourners like Pat Buchanan acknowledged, that Dolan had fought ferociously for conservative causes throughout the 1980s, raising millions through his pioneering “super PAC” to shrink government, crush unions, and back Republican candidates. Studiously ignored by his family and political friends, however, was an aspect of Dolan commemorated days later at an unauthorized memorial service at the Cathedral of St. Matthew on Rhode Island Avenue. The 50 gay men and women in attendance remembered him as one of their own, a resident of the closeted “secret city” within Washington, D.C., struck down by the same virus that had felled Rock Hudson and uncountable others.

By James Kirchick

Macmillan, 816 pp.

Like so many gay Washingtonians, Dolan led a double life, one that persisted even in death. After the funerals, his brother Tony, a White House speechwriter, took over the task of guarding his secret. As The Washington Post prepared to report on Terry’s hidden sexuality and death in 1986, Tony pulled every string to stop it. Ben Bradlee, the editor of the Post, had a gay brother—one whom he accepted—and he believed the public should know that such a prominent conservative activist, an ally of the “Moral Majority,” had died of AIDS, the disease that President Ronald Reagan refused to name. When Tony’s efforts to kill the story failed, he published a 29-page essay excoriating the Post for being “disrespectful of the public’s right to know; incapable of self-examination or introspection; self-righteous; arrogant and heartless in the relentless pursuit of those on its own enemy’s [sic] list.” He claimed that his brother had experienced a “religious conversion” before death and had renounced homosexuality. Head-spinningly, Tony charged the Post with succumbing to “homosexual intrigue” in service of “a special interest who wanted to claim my brother as well as other prominent people as one of their own.”

Why were the Dolans so desperate to contain Terry’s secret, even as gays and lesbians were coming out of the closet, either encouraged by the gay liberation movement or forced out by AIDS? Their Catholic faith had something to do with it, as did their conservative allegiances. But that wasn’t the whole answer. As James Kirchick describes in devastating detail in Secret City, the “American Century” was one of terrible oppression in the nation’s capital, where gays and lesbians were hunted by the FBI and treated as security threats equal to, if not greater than, America’s fascist and Communist enemies abroad. J. Edgar Hoover’s investigations into the State Department, the CIA, and the White House ended thousands of careers, marriages, and lives. The witch hunt continued over generations, producing a grim lineage of ruined names—Walsh, Welles, Offie, Kameny, Chambers, Hiss—that the Dolans had no wish to join. In his diatribe against the Post, Tony Dolan cited one of those names—Whittaker Chambers, an ex-socialist and “reformed” homosexual who famously accused the diplomat Alger Hiss of participating in a Communist cell—as he attacked the paper for failing to mention his brother’s deathbed sexual conversion. “You cannot write a story about Augustine of Hippo and not note that he became a Christian,” Dolan wrote, just as “you cannot write an account of Whittaker Chambers and leave out the part about his crusade for Western values and freedom.”

Though gay men and women have shaped Washington since its founding—among them Pierre Charles L’Enfant, the military engineer who planned the city—Kirchick focuses his account on 70 or so years of the 20th century. From the 1930s through the 1990s, America fought World War II and the Cold War. These crises pulled the country together against external enemies but sparked paranoia about “threats” from within. During these decades, homosexuality became an identity, defined first by the forces seeking to root it out and then reclaimed by those who bravely fought for their right to exist. Kirchick, an experienced journalist, draws together news clippings, correspondence, and archival materials to chronicle the “secret city”: the network of bars, bookstores, and cruising grounds where gay people, many of them powerful government figures, lived parallel lives.

The “American Century” was one of terrible oppression in the nation’s capital, where gays and lesbians were hunted by the FBI and treated as security threats equal to, if not greater than, America’s fascist and Communist enemies abroad.

A gay man himself, and an outspoken conservative, Kirchick pulls no punches in describing the contemptible behavior of right-wing (and some leftist) troglodytes who hounded homosexuals in the tabloids and Congress. He paints a particularly unflattering portrait of the Reagans, conservative icons who surrounded themselves with gays and lesbians in private but abandoned them publicly during the AIDS crisis. But Secret City, though engrossing, novelistic, and deeply sympathetic to minorities persecuted in the last century, does not carry its thesis forward to show how the same illiberal forces became incorporated into the present-day Republican Party, which, with its bathroom bans and “Don’t Say Gay” laws, has embraced intolerance as a platform. Instead, Kirchick’s book is concerned with battles of the past; he dedicates its roughly 800 pages to “all those who unburdened themselves of their secret, so that I did not have to live with mine.”

The story begins on a train, with a series of indecent propositions. On September 17, 1940, Sumner Welles, a high-ranking diplomat, attended the funeral of former Speaker William Bankhead in Jasper, Alabama. Headed home on the presidential train, Welles drank heavily with the vice president, among other notables, and then retired. In the middle of the night, Welles summoned several Pullman porters—Black men—to his cabin, and, one after another, offered them money for sex. They all refused. The story spread quickly in Washington, but journalists refused to report Welles’s indiscretions—at first. It was still considered inappropriate to delve into public officials’ sex lives. But the influential undersecretary of state had enemies, and war was coming.

A Harvard-educated scion of New England blue bloods, Welles aced the Foreign Service exam, becoming head of the State Department’s Latin American Affairs division at age 28. He was a friend of Eleanor Roosevelt’s, as well, and Franklin D. Roosevelt came to rely on his foreign policy advice over that of the actual secretary of state, an ailing political appointee named Cordell Hull. Hull and others, like the brilliant, ruthless young diplomat William Christian Bullitt, resented Welles’s influence with the president. FDR dismissed reports about the train episode and ignored demands from Bullitt and Hull to fire Welles. But a few years later, a wartime scandal would force his hand.

In 1942, police and federal agents raided a Brooklyn townhouse that served as a private club where gay men could fraternize. The story splashed across front pages after authorities alleged that a Nazi spy had been caught there, hoping to glean information from government officials who frequented the establishment. The press dubbed it the “Swastika Swishery” and teased that a “Senator X” also was alleged to have been present. An FBI investigation ensued, and the senator was eventually revealed as David Walsh of Massachusetts, chairman of the Naval Affairs Committee. Never mind that there was no evidence that secrets were divulged, and that the owner of the club eventually recanted his testimony about Walsh—the private lives of federal officials were now a matter of national security. What if foreign spies blackmailed gay men in government and forced them to give up state secrets?

Only one concrete example has ever been given to bolster this reasoning, which would be repeated in thousands of public inquisitions throughout the 20th century. In 1913, Alfred Redl, head of Austrian army counterintelligence, took his own life after being exposed as a Russian spy. The Hapsburg Empire suffered catastrophic defeat at the hands of the tsar during World War I, which authorities blamed, fairly or not, on Redl. And although his motivations were unclear, and the Russians paid him well, it became common wisdom across the Western world that Redl’s homosexuality had exposed him to blackmail, thereby bringing down an empire.

It eventually brought down Welles, too. Though Bullitt had had same-sex affairs, he didn’t hesitate to use the emerging gay terror to resurface the train story. He and Hull fed confidential affidavits to their allies in Congress, who forced Roosevelt to ask for his friend’s resignation. Welles was allowed to go quietly, claiming ill health, and he remained a prominent commentator on foreign affairs. But the floodgates were open. As part of their background checks, the FBI, the Civil Service Commission, and other federal agencies would probe thousands of employees’ sex lives. Kirchick estimates that between 7,000 and 10,000 federal employees would lose their jobs in the next decade because of their sexuality.

If the end of the war shifted attention from Nazi spies to Communist ones, it did nothing to stem the bloodletting among Washington’s gay community. Indeed, some of the Red Scare’s biggest controversies had a distinctly lavender tinge.

In 1948, a nebbishy journalist for Time magazine named Whittaker Chambers leveled an accusation that seized the nation: Years ago, he had been part of a Communist cell, and a fellow member was until recently a government official and had passed sensitive information to the Soviets. That was Alger Hiss, a sleek, well-bred former State Department diplomat, who would become a liberal cause célèbre as a victim of anti-Communist panic. (It wasn’t until after the fall of the Soviet Union that declassified documents appeared to show that Hiss had been a spy all along, though some still maintain his innocence.) The details of the case are well known and sometimes absurd, with federal agents at one point digging up a telltale microfilm canister from a pumpkin patch. Still, Kirchick resurfaces one largely ignored aspect: Chambers’s sexuality. In statements to the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), Chambers took a tone of deep humility as he repented of his former Communist sympathies and previous attraction to other men. “Ten or more years ago, with God’s help, I absolutely conquered it,” he told the FBI. The admission was strategic—Hiss had started a whisper campaign to smear Chambers as a disappointed would-be lover. The irony of Hiss, a leftist martyr, accusing the conservative Chambers of “fairy vengeance” is not lost on Kirchick.

HUAC’s hearings served as a model for Senator Joseph McCarthy, who frequently mixed gay slurs with his attacks on effete socialists in the State Department and the CIA. Those “dirty tricks” caused no offense to McCarthy’s closest aide, a conniving, closeted young lawyer named Roy Cohn, who would later mentor Roger Stone and Donald Trump. Cohn’s affection for a handsome young draftee named David Schine, and his attempts to obtain special treatment for him, led to the Army-McCarthy hearings, which sped the senator’s downfall.

Among the many lives destroyed by McCarthy and his allies, perhaps none was as consequential as that of Senator Lester Hunt of Wyoming. A Democrat, Hunt challenged McCarthy’s reign of terror by calling for the lifting of congressional immunity against slander charges. In 1953, his son, Buddy Hunt, was arrested after soliciting sex from an undercover officer. (As Kirchick details, police tactics at the time verged on farcical; vice squads bored peepholes in the walls of bathrooms and sent attractive undercover officers to entice suspected “perverts.”) Two McCarthyites, Senators Styles Bridges and Herman Welker, pressured the D.C. police to press charges and then used the case to blackmail the elder Hunt into resigning. Instead, on June 19, 1954, Hunt walked into his Senate office with a .22-caliber rifle, wrote notes to his staff and family, and then shot himself. The suicide rocked Washington but kept Buddy’s shame from the gossip pages. During the vote to censure McCarthy, later that year, the Senate observed a moment of silence for Hunt.

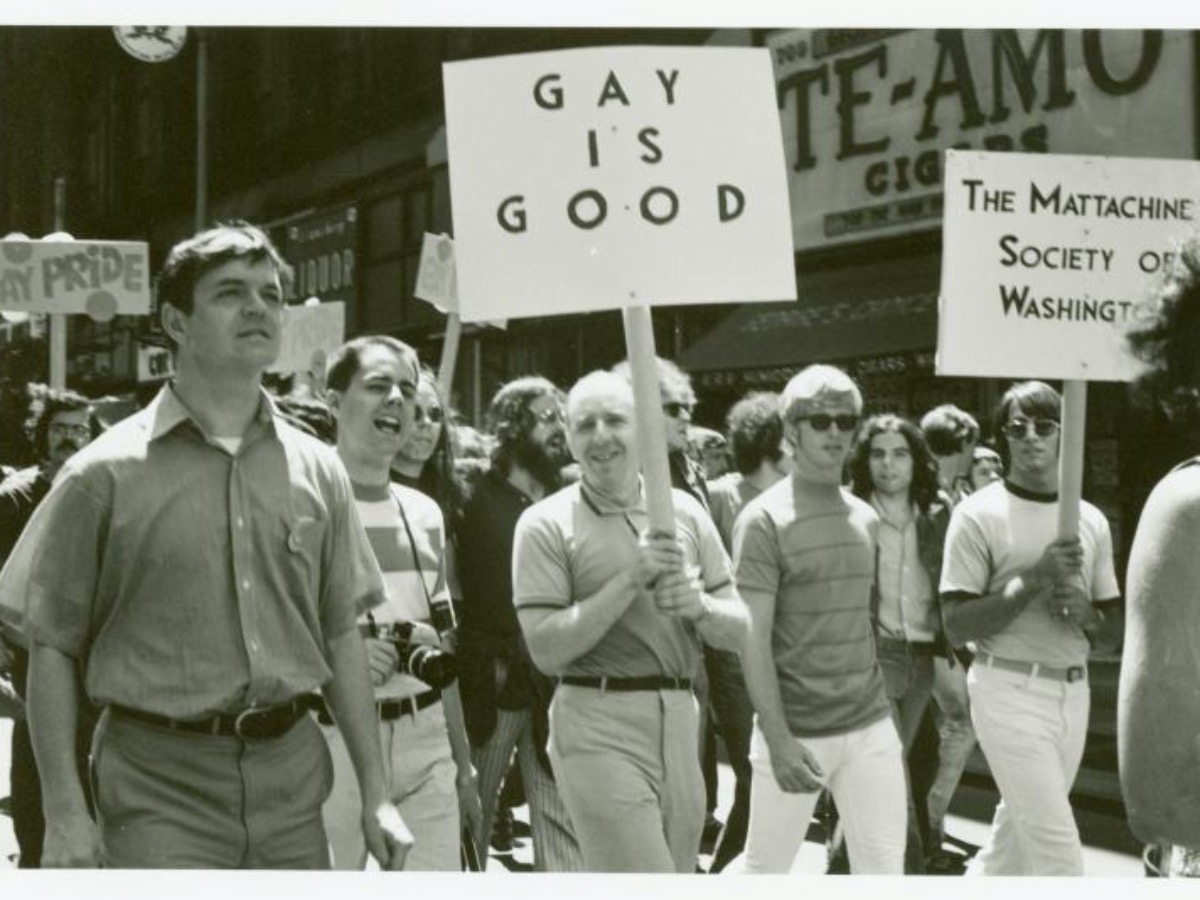

Three hundred pages of cruelty and silent misery pass before we meet the people who began to fight back. In November 1961, the first meeting of the Mattachine Society of Washington convened at the Hay-Adams hotel across the street from the White House. In attendance at the gay rights gathering were 16 men; their leader, Frank Kameny; and an undercover officer of the Metropolitan Police. Kameny was well acquainted with antigay surveillance. Formerly an astronomer for the U.S. Army Map Service, he was fired, in 1957, after investigators learned of a prior conviction for homosexual solicitation in San Francisco. Kameny appealed to the Supreme Court, which declined to take the case. Still, he wouldn’t let the nation’s highest court end his fight for gay rights, and certainly not a young plainclothes officer gate-crashing his meeting. “I understand that there is a member of the Metropolitan Police Department here,” he said after concluding his remarks at the Hay-Adams. “Could he please identify himself and tell us why he’s here?” The officer mumbled an excuse and left the room.

The Mattachine Society, which had chapters in San Francisco and New York, at first mainly concerned itself with letter-writing campaigns and leafleting, seeking to activate gay people politically and raise awareness among elected officials. But in 1965, the group staged what is believed to be the first public demonstration for gay rights—a picket line outside the White House. Over the years, Kameny would become a behind-the-scenes adviser in prominent court cases backing gay rights. In the following decade, he helped persuade the American Psychiatric Association to rescind its definition of homosexuality as a mental disorder. The Mattachine Society of Washington also disseminated a newsletter for the burgeoning gay community, which congregated at secretive bars like the Chicken Hut, the Rendezvous, and the Ace of Spades, many of which required passwords to enter. To visit such an establishment was a risk for closeted government officials. At that time, gay men adhered to the “Code”: an unspoken agreement to keep each other’s identity secret, even in the face of the harshest political disagreements.

In both the Kennedy and Johnson administrations, gayness was more or less accepted in private—Kirchick tells an amusing anecdote about John F. Kennedy’s pleased reaction when told that a gay man had complimented his posterior—but punished in public. JFK’s closest confidant was Lem Billings, a gay classmate from boarding school who hung around the White House so often he became known as the “First Friend.” Yet the investigations and firings continued apace; and when Lyndon B. Johnson became president, one of his closest aides, Bob Waldron, who was “something very close to a substitute son,” was quietly jettisoned after a background check revealed that he had once made a pass at a male friend. Barred from government, with their cause not yet a priority among activists, gays and lesbians mobilized in other ways, supporting the civil rights movement and its signature legislation of 1964 and 1965.

Around the time JFK was elected, a novel by the Times reporter Allen Drury won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. Advise and Consent told the story of Brig Anderson, an upstanding Utah senator who defies reactionary anti-Communists but is driven to suicide by a blackmail plot that threatens to reveal a long-ago homosexual liaison. The shadow of Lester Hunt was unmistakable. With the release of a celebrated Hollywood adaptation a few years later, the real-life senator entered the public consciousness as legend, in turn shaping lives to come. During a year off from Harvard, a young gay man from Massachusetts named Barney Frank read the book and decided never to reveal his secret. (He wouldn’t change his mind until 1987, when he became one of the first congressmen to come out of the closet.)

Even Watergate cast a lavender shadow. In 1969, a Nixon fixer named Murray Chotiner was sidelined by other aides as his longtime boss entered the Oval Office. As revenge, Chotiner spread a rumor that several White House staffers were known homosexuals; it sparked a press stakeout and an FBI investigation. Richard Nixon’s band of dirty tricksters—Attorney General John Mitchell, Chief of Staff Bob Haldeman, aide John Ehrlichman—swore oaths to the Bureau that they were not homosexuals, and that no “homosexual activities” ever took place at the Watergate Hotel or Apartments. Later, setting off the earliest inklings of the scandal that would bring down a president, Nixon flunkies known as “the Plumbers” broke into a Beverly Hills psychiatrist’s office, seeking proof that Daniel Ellsberg, the Pentagon Papers leaker, was gay.

Meanwhile, gay people began to demand equal rights. During the 1970s, the community ventured into the open, with establishments like Lambda Rising, an LGBTQ bookstore, and the Eagle, a nightclub, no longer hiding behind closely guarded doors. The Mattachine Society’s newsletter had grown into a gay newspaper, the Washington Blade, which reported victory in court cases establishing equal protection under the law. In 1975, Kameny, who devoted his life to the movement—he couldn’t afford medical care for years—crowed that the Civil Service Commission had reversed itself: Homosexuals could no longer be fired, as he had, solely based on their sexual orientation.

If it wasn’t clear already, Secret City is primarily a book about gay men; Kirchick acknowledges this, noting that men, not women, held power and thus attracted more persecution for pursuing the wrong kind of love. Lesbians back then noticed this disparity, too. “Fuck You, ‘Brothers’” was the title of an essay read by Nancy Tucker at a 1971 meeting of the Gay Liberation Front. She announced that she was leaving the movement because it offered her nothing and was based on male problems: “entrapment, police harassment, blackmail, tea room assignations, venereal diseases.” “I’m leaving,” she said, “because I’m tired of coping with massive male egos, egos which cannot comprehend how anyone could want to have nothing to do with a male-dominated movement.”

But a strange new disease, in early reports resembling a kind of pneumonia or flu, would draw gay men and women back together.

Adolfo, Calvin Klein, Bill Blass, James Galanos, Geoffrey Beene, Perry Ellis—the list of fashion designers that the activist Larry Kramer rattled off in 1983 had something in common, and not just that they were gay. They all dressed Nancy Reagan, whose fashion sense and entourage of gay friends had made her something of a camp icon—some called her “Queen Nancy.” But, as Kramer noted, speaking at a rally for his nonprofit Gay Men’s Health Crisis, when it came to standing by their friends in public, she and Ronald were nowhere to be seen. “Mrs. Reagan,” Kramer asked, “don’t you think you could get your husband off his Levi 501s to help the dying brothers of your best friend?”

Kirchick speculates why Ronald Reagan was so conspicuously silent on AIDS for years. Perhaps it stemmed from rumors that had plagued his staff back in Sacramento; maybe he was sensitive about appearing beholden to liberal Hollywood and its queer, left-wing agenda. As Kirchick recounts, Reagan’s past eventually caught up with him and forced him to act.

The “best friend” Kramer mentioned was Rock Hudson. A paragon of Hollywood masculinity, Hudson also happened to be a close associate of the Reagans and a closeted gay man. In 1984, Nancy Reagan and Hudson sat at the same table at a state dinner. She didn’t notice the purple lesion behind his ear, but she did make a concerned remark about his weight. “You’re too thin,” she told him. “Fatten up.”

In July 1985, Hudson, dying of AIDS, made a fateful trip to Paris. A French hospital held a treatment that he hoped would save his life, but officials there wouldn’t let him in—he was a foreigner. Desperate, Hudson asked the Reagans to intercede. They refused. But as news spread that a huge star was deathly ill with the disease, it became impossible to ignore. In September, with 12,000 Americans dead or dying, Reagan acknowledged AIDS in response to a reporter’s question, calling it “a top priority with us.”

A month later, Hudson died. The Reagans released a statement, drafts of which Kirchick has dug out from their presidential library in California. An initial version called him “our friend” and expressed “profound” sorrow over his death; in a photocopy printed in the book, those words have been crossed out, erasing any personal connection between the Reagans and their longtime friend. Toward the end of Reagan’s presidency, as he and Tony Dolan crafted a speech urging Mikhail Gorbachev to “tear down this wall” separating a free Berlin and an oppressed one, 40,849 Americans had already died of AIDS.

The “Gay ’90s” were a decade of firsts. More and more people came out in government, and AIDS treatments grew more effective and widely available. In 1993, a million people descended on the National Mall for the March on Washington for Lesbian, Gay, and Bi Equal Rights and Liberation. (Transgender rights were included on the march’s list of demands, but a vote to include trans people in the name failed.) In 1995, President Bill Clinton ended the ban on security clearances for gays, a prohibition that had denied the nation the services of so many promising people. He also signed the Defense of Marriage Act and “don’t ask, don’t tell,” compromises that forestalled more regressive action but set up the next decade’s gay rights struggles.

At the end of the book, Kirchick reflects,

To assess the full scale of the damage that the fear of homosexuality wrought on the American political landscape, one must take into account not only the careers ruined and the lives cut short, but something vaster and unquantifiable: the possibilities thwarted.

Take David Mixner, a prominent gay activist born three days apart from his friend Clinton, who lamented in his memoir that his sexuality had prevented him from holding public office. Citing Mixner and others, Kirchick asks,

How many other patriotic Americans declined to run for public office, withheld their mastery of a foreign language, refrained from applying their hard-earned scientific knowledge, or forwent serving their country in myriad other ways solely because of its hostility to the way they loved other people?

Kirchick has written a comprehensive and deeply humane work of history, but he doesn’t extend this question to the present day. His other writings suggest, unfortunately, that this may be because he lacks the same compassion for some of today’s marginalized groups. In a 2019 Atlantic article titled “The Struggle for Gay Rights Is Over,” Kirchick proclaimed that America is becoming a “post-gay country,” where same-sex marriage is legal, an “out” gay man can be a credible presidential candidate, and 70 percent of Americans say homosexuality should be accepted. With so many victories, Kirchick accuses present-day activists of “mission creep”—of pushing forward with largely irrelevant struggles, refusing to accept that they have already won. He writes,

For many of those whose political identities have been shaped by crusades against government discrimination and pervasive societal ignorance, victimhood is too essential an identity to be so easily discarded.

Government discrimination continues, just not against people like Kirchick. This year, an executive order from Texas Governor Greg Abbott authorized child abuse investigations into parents who affirm their transgender children’s identities. Other states have banned transgender participation in sports, transgender use of public bathrooms, and discussion of nontraditional gender and sexual identities in classrooms. The Trump administration banned most transgender military service and removed federal protections against discrimination based on gender identity. In his Atlantic article, Kirchick acknowledged some of these things, only to dismiss them in the same breath as “the conflation of transgender issues with the gay-rights movement.” What this framing ignores is something that, ironically, Secret City illustrates very well—that oppressive social movements don’t simply disappear when defeated in one arena; they metastasize across generations, finding expression in hatred of groups not yet admitted to the mainstream. McCarthy begat Cohn begat Trump. Left unchecked, they’ll happily undo progress that once seemed unassailable.

Kirchick has written a comprehensive and deeply humane work of history, but he doesn’t extend this question to the present day. His other writings suggest, unfortunately, that this may be because he lacks the same compassion for some of today’s marginalized groups.

So others will be left to draw those parallels. What advances in science, policy, and politics will we lose in this century as we ban trans people from public life, lock migrant children in cages, and imprison countless Black men? How many personal tragedies are playing out unnoticed today, and how many villains are going unpunished? Who will be the Kirchicks of the next century—chroniclers tasked with sifting through bygone sorrows to deliver some measure of justice through the acknowledgment, at least, that harm was done? Despite our best efforts to uplift those on the margins, some number will inevitably remain invisible, like the secret city itself.