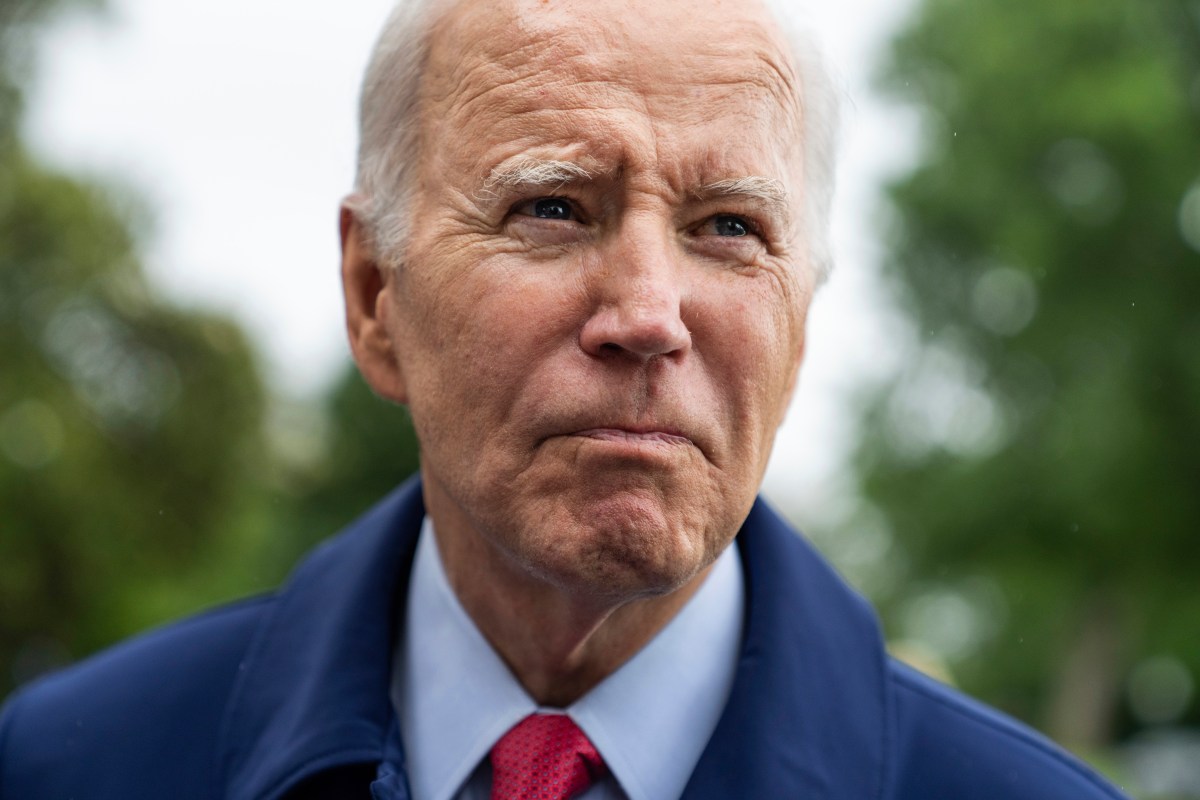

On May 25, Noah Rothman of the conservative National Review wrote, “Joe Biden promised to satisfy the public’s desire for a return to normalcy and failed to deliver.”

Two days later, Biden achieved peak normalcy: a bipartisan budget agreement with the leader of the House Republican majority.

What did Biden promise exactly? In October 2020, Biden addressed the nation from Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, conjuring up Abraham Lincoln’s vision of a truly United States following the Civil War, and said:

The country is in a dangerous place. Our trust in each other is ebbing. Hope seems elusive. Too many Americans see our public life not as an arena for mediation of our differences, but, rather, they see it as an occasion for total, unrelenting partisan warfare. Instead of treating each other’s party as the opposition, we treat them as the enemy. This must end.

We need to revive the spirit of bipartisanship in this country, a spirit to being able to work with one another. When I say that—and I have been saying it for two years now—I’m accused of being naive. I’m told maybe that is the way things used to work, Joe, but … Well, I’m here to tell you, they can, and they must, if we are going to get anything done.

Biden was not naïve. He has made Washington functional again.

The debt-limit deal is only his latest bipartisan accomplishment, following historic legislation in support of infrastructure, semiconductor manufacturing, gun safety, Ukraine aid, and postal service reform.

You may not know that Biden, so far, is the first president to manage the government without any agency suffering a shutdown of any length of time since Gerald Ford, with the exception of George W. Bush. With a two-year budget agreement in hand, the chances of shutdown between now and Election Day 2024 have dropped considerably.

Yes, the debt limit is a needless source of national anxiety, and Democrats ought to have rid the country of it when they had the chance (as I argued two years ago). But this year’s debt-limit drama wasn’t all that dramatic. Once Biden and House Speaker Kevin McCarthy began negotiating in earnest, a deal was struck in a mere 18 days. The debt-limit processes in 1995-1996, 2011, and 2013 were far more harrowing and, save for 2011, included tumultuous government shutdowns. This negotiation was refreshingly normal.

Was it too normal? Some progressives fear that negotiating with McCarthy, instead of circumventing him by asserting Fourteenth Amendment powers, allowed Republicans to normalize “hostage-taking” tactics and set an unhelpful precedent.

But true legislative hostage-taking involves specific ransom demands to avoid a catastrophic default. In 1995, House Speaker Newt Gingrich explicitly threatened default if President Bill Clinton didn’t sign draconian cuts to Medicare, Medicaid, education, and environmental protection. In 2013, Senator Ted Cruz and others threatened default if President Barack Obama didn’t defund the Affordable Care Act. The barely unspoken message was: Do what I say, or the economy gets it. These were absurdly unreasonable asks—so unreasonable that the public recoiled, Democrats resisted, and Republicans caved.

What McCarthy did this year resembled what his Democratic predecessor, Nancy Pelosi, did in 2019 when Democrats controlled the House but not the Senate or the presidency—a power balance equivalent to what the current speaker faces.

Back then, the federal government was laboring under a convoluted set of budget restraints stemming from the 2011 debt limit deal, known as the “sequester.” Subsequent legislation temporarily raised the spending caps to avoid the sequester’s across-the-board cuts. Those caps were due to expire on October 1 of that year. Pelosi refused to hike the debt limit unless it was attached to extended sequester relief, but she stopped short of demanding an exact spending level.

In a private meeting with President Donald Trump and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, the White House budget director at the time, Russ Vought, lobbied hard for a “clean” debt limit increase without conditions. McConnell, according to Politico, better understood the political constraints. “Listen buddy,” McConnell lectured Vought, “we’re not doing a clean debt ceiling. Get a budget caps deal.” They did, increasing the spending caps by $320 billion over two years. The Congressional Budget Office projected that the agreement would add $1.7 trillion to the 10-year budget deficit.

McCarthy wanted lower, not higher, spending. But similar to Pelosi, he did not insist on an amount. When the House passed his “Limit, Save, Grow Act” on a party-line vote—which the Congressional Budget Office estimated would save $4.8 trillion over 10 years—he characterized it as a bid, not a demand. Not committed to deep cuts, he negotiated a much smaller deal with Biden, estimated to save $1.5 trillion, subtracting almost as much as the Trump-Pelosi deal added.

These are modest agreements. (According to the economist Mark Zandi, the Biden-McCarthy deal will only nick 0.15 percent off the Gross Domestic Product next year.) Even if Democrats effectively junked the debt limit two years ago, bipartisan negotiations this year before the deadline to keep the government open—September 30, when the fiscal year ends—would likely have produced outcomes similar to what is before us today. This was, in essence, a normal budgetary negotiation in a divided Washington.

One need not love every aspect of this bipartisan agreement to celebrate bipartisanship’s revival. Of course, relative comity cannot easily produce legislation with comprehensive solutions to pressing problems. But without a modicum of bipartisanship, periods of divided government would produce destabilizing gridlock. Once the 2022 midterm elections ended Democratic control of the executive and both legislative chambers, the question we faced was whether Congress could keep the lights on in a time of extreme political polarization.

McCarthy deserves his share of the credit. He shrugged off the threats from the wannabe nihilists in the far-right House Freedom Caucus. For example, Representative Matt Gaetz for months claimed to have McCarthy in a straitjacket since any disgruntled member can introduce a “motion to vacate” and try to oust the speaker. Yet McCarthy ignored the Freedom Caucus’s wish list and negotiated an agreement without their input. In the wake of the deal, a few upset Republicans publicly mused about taking McCarthy out. Then, according to Politico, during a Tuesday night meeting of House Republicans, Freedom Caucus member Representative Randy Weber told his dissenting colleagues to “cut it out.” After the meeting, talk of revolt quickly dissipated. McCarthy appears to have won the stare-down.

Biden won something, too. While the president continues to warn about right-wing extremism—justifiably so—he has seized the higher ground by not treating the entire Republican Party “as the enemy.” He found Republicans willing to negotiate in good faith. He got things done. He has made Washington normal again.

Correction: An earlier version of this piece said Gerald Ford was the last president not to endure a government shutdown. It was George W. Bush.