There are mass shootings and school shootings. There are shootings at banks, supermarkets, churches, synagogues, military bases, Zumba studios, and kids’ birthday parties. The shocking sounds of gunfire have become the background music, the soundtrack, to American life. It’s scrutinized in the media and the academy, discussed in Congress, and adjudicated before the Supreme Court—and in this excellent recent two-part investigation here at the Washington Monthly, one aspect is still poorly understood.

Though the U.S. is the most dangerous wealthy democracy in the world when it comes to guns, gun violence varies enormously by region. It’s as if Americans live in separate countries, some with areas of the nation having gun violence profiles that look like Canada’s, others resembling the Philippines. And, as I showed in a recent research package at Nationhood Lab, the project I run at Salve Regina University’s Pell Center for International Relations and Public Policy, the reasons for this go back centuries, and are part and parcel of dominant cultural heritages laid down by the rival colonial projects that spread across our continent in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries. Reducing levels of deadly violence in the U.S., I argued there, won’t be easy, but understanding the nature of the problem is an essential first step.

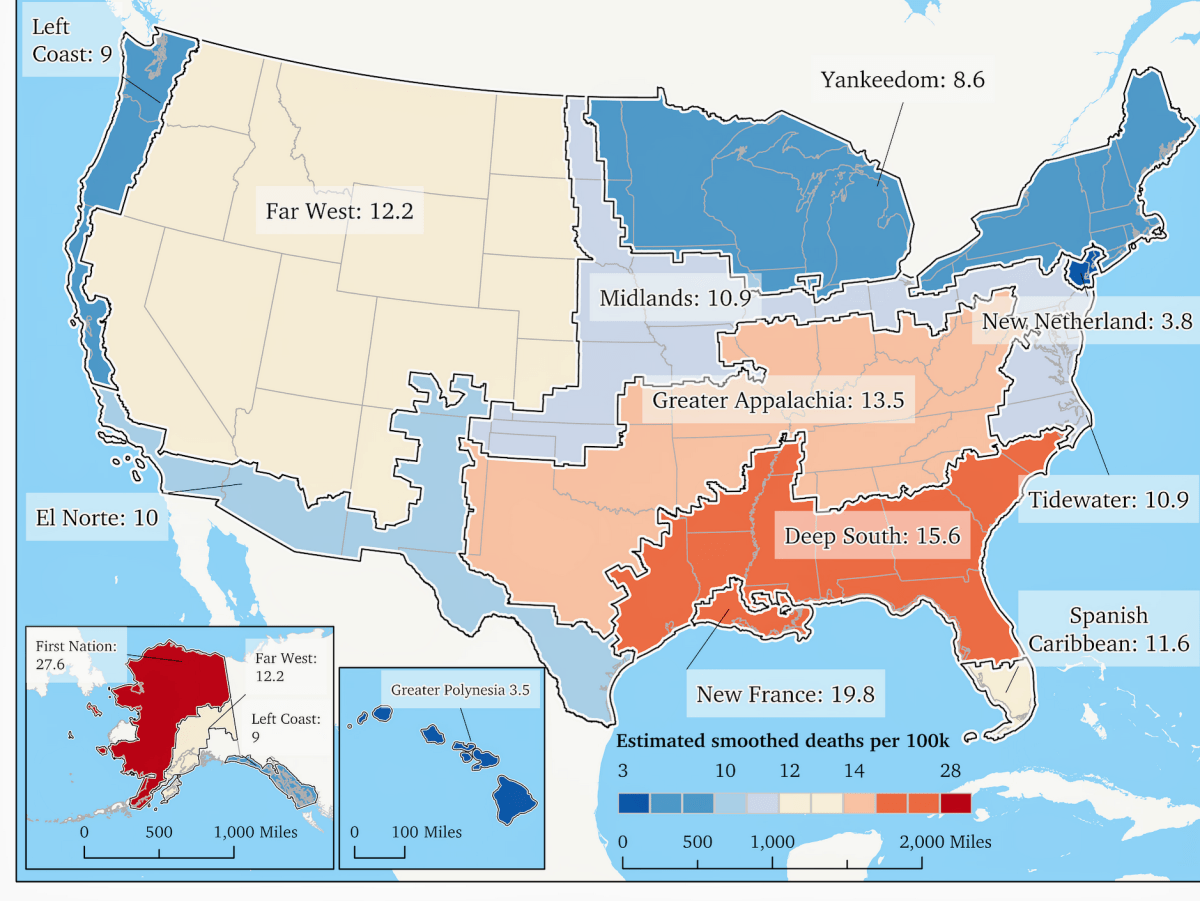

Our initial “geography of gun violence” package received national attention, partly due to a companion story I wrote for Politico that, as of last month at least, my editors told me, was among their most-read stories of 2023. (I say this not to brag but to illuminate, I think, the immense interest in guns and our divided polity.) It showed that “red” regions in the South—defined via the model in my 2011 book American Nations: A History of the Eleven Rival Regional Cultures of North America—had per capita homicide and suicide rates two or three times greater than those in the Northeast and West Coast, and seven to nine times greater than in “New Netherland,” the Dutch-settled zone that’s roughly analogous to today’s Greater New York City and is the safest area of the country by far. The differences persisted in urban or rural counties, homicides, or suicides.

Some readers were curious if there were correlations between gun ownership and gun death levels and also if there was any high-resolution (that is, county-level) polling data that could illuminate subregional differences in support for various gun reforms. At first, I thought not—Congress has effectively forbidden the creation of a federal gun sale database, and polling samples are rarely big enough to power the American Nations model; even when they are, outsiders can rarely access the county-level or even congressional district-level results. But I’ve since tapped into a Democracy Fund Voter Study Group & UCLA Nationscape project, a massive public data set of weekly polls conducted from summer 2019 to Election Day 2020 that asked more than half a million Americans about a broad range of issues and attitudes.

I’ve recently posted a follow-up piece at Nationhood Lab that uses UCLA Nationscape polling data from the second half of 2020 to illuminate some unanswered questions. In almost every gun-related question asked, Nationscape’s regional patterns closely matched our data on gun deaths, with the respondents in the safer regions reporting they owned fewer guns and favored more robust gun control policies than those in the most dangerous ones.

It turns out the country’s safest region, New Netherland, has the lowest levels of gun ownership: 78 percent of respondents there reported that nobody in their household has a firearm. Two other regions with low per-capita gun deaths, El Norte (Spanish-colonized areas of the Southwest) and Left Coast (the coastal strip in the Pacific side of the mountains running from Monterrey, California to Juneau, Alaska), also had low gun ownership: 65 and 64 percent of households respectively are gunless. Two regions spanning the Northeast and northern Midwest—Yankeedom and the Midlands—were also less armed, with 62 and 58 percent of homes foregoing guns. But the three large nations with the highest per capita gun deaths—Greater Appalachia, the Deep South, and the Far West—had the fewest gun-less households at 44, 50, and 51 percent, respectively.

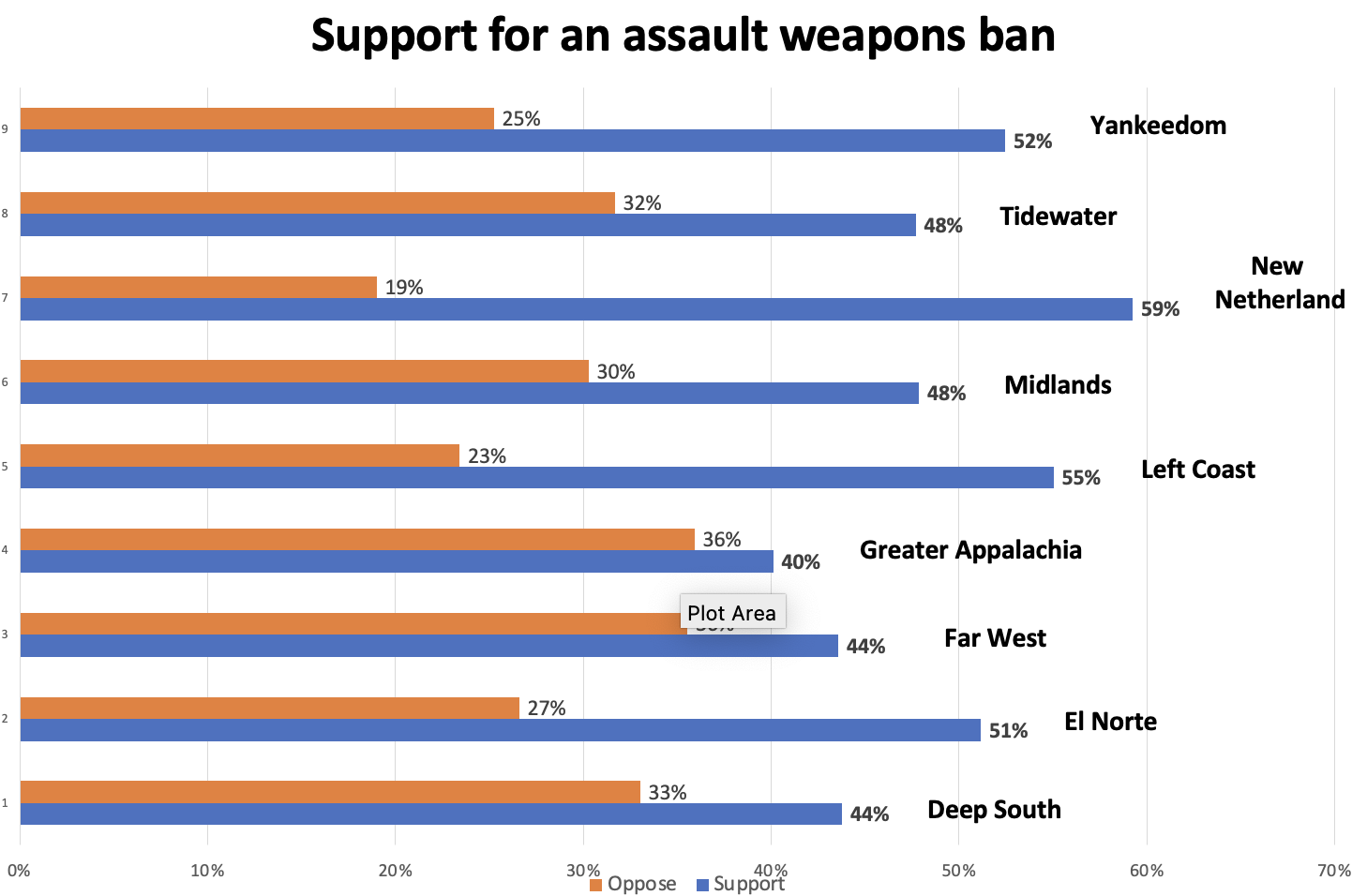

Nationscape also asked respondents if they support everything from requiring universal gun purchase background checks to banning firearms. The results are encouraging—if you think the status quo is unacceptable. There was near universal support in every region for background checks, with higher percentages of support in each than the proportion of Americans that believe NASA put astronauts on the moon or that the Earth is round. There was also majority support in every region for banning assault-style rifles and high-capacity magazines, albeit with margins ranging from a few percent (or even a fraction of a percent) in the Far West, the Deep South, and Greater Appalachia to massive 30 and 40 point margins in the “blue” regions. (You can read the details here.)

The gun lobby can rest easily on one point, however. There’s no constituency in any region for taking away all your guns. Support for a firearm ban was underwater by double digits in every region—by about 50 points in Yankeedom and the Midlands and more than 60 in the Far West and Greater Appalachia. The only place where it wasn’t a total blowout was—you guessed it—New Netherland, with “only” a 16-point deficit.

Americans may be nations apart in gun violence, but we’re a lot closer together when it comes to doing something about it.