He is “both physically and intellectually incompetent to perform the many, varied, arduous, and important duties which must devolve upon every President of the United States.”

No, that’s not a Republican politician attacking Joe Biden. That’s an attack by a Democratic politician on William Henry Harrison, the 1840 Whig Party nominee.

Harrison was, at the time, the oldest presidential candidate ever. According to historian Ronald G. Shafer in his book, The Carnival Campaign, Democrats embarked on a “whispering campaign hinting that the old general, at age sixty-seven, was in such poor health that he might not survive the campaign.” (He would die days after his inauguration, but most likely from contaminated water, not old age.)

Democratic newspapers dubbed him “Old Granny Harrison.” One polemicist for a Baltimore rag sought to deride the former Territory of Indiana Governor and Ohio Senator as an aging drunk but famously missed the target: “Give him a barrel of hard cider and settle a pension of two thousand a year on him and, my word for it, he will sit the remainder of his days in a log cabin by the side of a ‘sea coal’ fire and study moral philosophy.” The Whigs turned “Log Cabin and Hard Cider” into a popular campaign slogan, painting Harrison as an authentic everyman.

Still, Harrison and his supporters deemed it necessary to neutralize concerns about age and inaugurated what became a timeless tradition. “For the first time in a presidential contest,” writes Shafer, “the Whigs trotted out a physician to vouch for a candidate’s physical and mental fitness.” Also, a presidential candidate gave campaign speeches for the first time, during which Harrison mocked claims he was a “decrepit old man.”

The Democratic incumbent, Martin van Buren, was probably doomed to defeat, as he presided over a severe economic depression. But the campaign provided the first data point suggesting that ageist attacks can’t easily sway a presidential election.

In fact, we have no example in American history of a presidential candidate losing primarily because of old age.

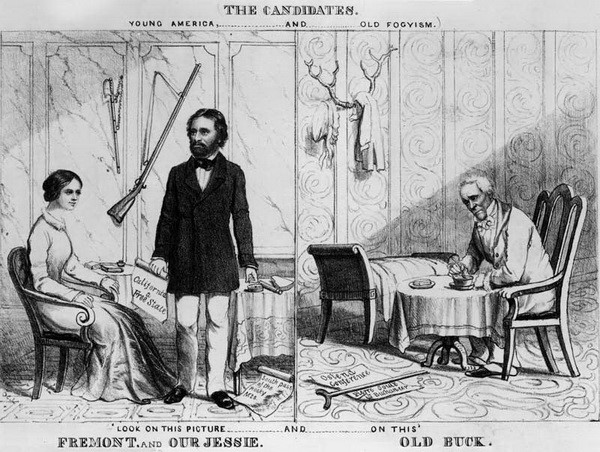

Sixteen years after Harrison’s victory, it was the Democratic Party’s turn to nominate a sexagenarian: James Buchanan. The newly formed Republican Party (partly composed of former Whigs who opposed slavery) tapped a 43-year-old swashbuckling explorer and soldier, John Frémont. Republicans sought to exploit the 22-year age gap and frame the choice as the now familiar past versus the future. One cartoon epitomized Frémont and his sophisticated wife Jessie as “Young America” and the lifelong bachelor and career politician Buchanan as a sad and lonely poster boy for “Old Fogyism.”

Once again, the juxtaposition of age could not supplant the issue of the day, which in 1856 was slavery. Democrats dubbed members of the new party “Black Republicans” and, because Republicans drew support mainly from the free North, charged them with sowing geographic division. Buchanan counseled an ally, “The Union is in danger and the people everywhere begin to know it. Black Republicans must be … boldly assailed as disunionists and this charge must be reiterated again and again.” The Pennsylvanian was able to add northern states to the solid Democratic South and forge a winning coalition, limiting Fremont to the most northern states.

In the 19th century and early 20th century, the average white male adult could expect to live about 60 years, give or take. After Buchanan, nearly a century passed before another 60-plus politician was elected president, and it was extremely rare for one even to be nominated. Between the Civil War and the beginning of World War II, no one over 60 was the nominee of a major party except for Samuel Tilden, who was 62 when he lost the disputed election of 1876.

Franklin D. Roosevelt cleared 60 years of age when he ran for his fourth term in 1944. While the public did not know Roosevelt was mere months away from his death, there were signs. Reporters at off-the-record press conferences saw memory lapses, hand tremors, and a slacked jaw but didn’t share that information with the public. Democratic leaders were worried enough that they maneuvered to dump the left-wing Vice President Henry Wallace from the ticket in favor of Harry Truman (who just turned 60.) During an August campaign stop, Roosevelt made an uncharacteristically “dull and wandering” national radio address, in the words of his Secret Service bodyguard, that precipitated a drop in his poll numbers.

While the Republican nominee, New York Governor Thomas Dewey, didn’t make any direct accusations, his allies waged a “whispering campaign about the President’s health,” according to historian David M. Jordan, in FDR, Dewey and the Election of 1944. Republicans would make oblique references to the “tired old men” in the White House and boast about the “youth of their candidates.” But after Roosevelt braved the rain in a late October campaign tour of New York City, followed that evening by a strong foreign policy address, the rumormongering subsided. With the leadership of the succeeding war effort as the overriding issue, not age, Roosevelt won handily, albeit by the narrowest popular vote margin of his four campaigns, 7.5 percentage points.

Eight years later, in 1956, 66-year-old Dwight D. Eisenhower—the third oldest person to serve as president at that point in history behind Buchanan and Harrison—was cruising toward reelection even though had suffered a heart attack in the previous year and spent most of June recovering from intestinal surgery. Yet, with the nation in relative peace and prosperity, Democratic nominee Adlai Stevenson had little opening to exploit and seemed doomed to lose to Ike again after getting pummeled by him in 1952.

So, Stevenson bet on age. As described by Kenneth S. Davis in The Politics of Honor, the former Illinois Governor’s strategy was premised on a “public display of energy and stamina which Eisenhower could not match, indicating, as mere words could never do, the contrast between a relatively young man in the full tide of vigorous health and an aging man whose health was waning.”

The strategy completely backfired. Stevenson’s itinerary from late summer through the fall of 1956 was “worse than grueling.” According to Porter McKeever, in Adlai Stevenson: His Life and Legacy, “On TV screens and in personal appearances, he often appeared tired, driven, harassed, and lacking in control. Without time to absorb the content of his speeches, their delivery was often stumbling, uncertain, unconvincing.”

Stevenson threw away all subtlety for his final speech: “I must say bluntly that every piece of scientific evidence we have, every lesson of history and experience, indicates that a Republican victory tomorrow would mean Richard M. Nixon would probably be president within the next four years.” It was another misfire. Eisenhower won easily, with a slightly bigger popular vote margin than in his first contest with Stevenson. He would survive his second term, outlive Stevenson by four years, and not pass away until 1969 at age 79.

After Eisenhower, no one over 60 was elected until 1980, when a 69-year-old Ronald Reagan broke Harrison’s record as the oldest person ever elected President. Four years later, in the run-up to the first general election debate, Reagan was crushing his Democratic opponent Walter Mondale in the polls. But Reagan, usually a sparkling communicator, delivered a subpar debate performance.

Nothing happened as startling as Rick Perry’s infamous “Oops.” But as The New York Times reported, “Mr. Reagan appeared more subdued and was sometimes tentative in his answers. Mr. Reagan’s voice was noticeably quavering, particularly in the early going. At other times, the President appeared angry at suggestions that he lacked compassion.”

Mondale’s surrogates, especially the late Representative Tony Coelho, immediately saw an opportunity. “Reagan showed his age,” Coelho told the Times, “The age issue is in the campaign now, and people like me can talk about it, even if Mondale can’t.” Asked if the president was “doddering,” according to the Washington Post, Coelho said, “Well, he didn’t quite drool.”

In the period between the first and second debate, news coverage of the “age issue” increased, and Reagan’s lead decreased, from 18 to 12 points in the ABC News/Washington Post poll, from 26 to 13 points in the CBS News/The New York Times poll.

Yet Reagan’s lead remained sizeable. The big reductions in the margin obscured that Reagan wasn’t losing support as much as Mondale—who before the debate wasn’t reaching 40 percent—was consolidating Democratic support.

Mondale hoped age concerns would only grow after the second debate, during which he repeatedly claimed Reagan lacked knowledge of critical details and stressed that “the President must know what is essential to command.”

Reagan’s overall performance in the second debate wasn’t much better than his first. He started wobbly. When asked about “a CIA guerrilla manual for the anti-Sandinista Contras whom we are backing, which advocates not only assassinations of Sandinistas but the hiring of criminals to assassinate the guerrillas we are supporting in order to create martyrs,” Reagan awkwardly admitted there was a manual “turned over to the agency head of the CIA in Nicaragua to be printed” who “excised” several pages, yet some of the original copies “got out.” Upon being pressed by the questioner, Reagan backtracked: “I’m afraid I misspoke when I said a CIA head in Nicaragua. There’s not someone there directing all of this activity.”

That potential gaffe was forgotten once Reagan was asked if there is “any doubt in your mind that you would be able to function” in a crisis. Reagan crisply answered, “Not at all … and I want you to know that also I will not make age an issue of this campaign. I am not going to exploit, for political purposes, my opponent’s youth and inexperience.” The crowd erupted in laughter. Not even the 56-year-old Mondale could resist laughing. The age issue seemingly ceased to be.

But was age ever a cutting issue? Riding the wave of a booming economy, Reagan was always far ahead of Mondale in the fall campaign, even after the first debate. As in 1944 and 1956, the election ultimately turned on how well the incumbent delivered on peace and prosperity, not how well the incumbent was aging.

Granted, not every elderly presidential candidate has been able to trade on accrued wisdom to stave off younger opponents. At 64, George H. W. Bush was able to succeed Reagan. But in his 1992 reelection bid, he had to face the 46-year-old Bill Clinton during high unemployment. Clinton framed Bush as a relic who was “out of touch, out of ideas, and out of time” and attached to the “stale, failed rhetoric of the past.”

In 1996, when Clinton faced reelection against Robert Dole, the first septuagenarian presidential nominee, the Democrat didn’t really have to make age an issue because everyone else did it for him. (“A lot of people would look at a glass as half empty,” joked David Letterman, “Bob Dole looks at the glass and says, ‘What a great place to put my teeth.’”) Still, Clinton treated Dole much as he did Bush.

Dole tried to turn his age into an asset in his nomination acceptance speech. Peddling nostalgia, he offered, “Let me be the bridge to an America that only the unknowing call myth. Let me be the bridge to a time of tranquility, faith, and confidence in action.” At the Democratic convention two weeks later, Clinton rejoined, “We do not need to build a bridge to the past; we need to build a bridge to the future.”

Dole tried to recast his remarks in the first debate, claiming he, too, wanted “a bridge to the future.” In the second debate, when the moderator raised age, Clinton said, “I don’t think Senator Dole is too old to be president. It’s the age of his ideas that I question.”

In 2008, we had another fortysomething-versus-seventy-something matchup featuring Barack Obama and John McCain. The younger Obama deployed an “out of touch” attack like Clinton but with more edge. The narrator in the TV ad “Still” mocked McCain for admitting “he doesn’t know how to use a computer [and] can’t send an email,” then tacked on that he “still doesn’t understand the economy.”

Bush, Dole, and McCain lost. But they still would have lost if those three candidates were 20 years younger. Bush was an incumbent during a bad economy. Dole was challenging an incumbent during a good economy. McCain was trying to succeed a president from his party during an unpopular war he had championed and the worst economy since the Great Depression. To the extent age was a campaign tactic, it was always tied to the candidate’s economic platform. We have no example of age being successfully weaponized on its own, irrespective of other issues.

Biden, who turns 81 in November, is facing openly ageist attacks, free of any coy subtlety. Donald Trump, who is only four years younger, has said Biden “can’t string two sentences together” and has the “mind, ideas, and I.Q. of a first grader.” Other Republican candidates, such as Ron DeSantis, Chris Christie, and Nikki Haley, have speculated, or flatly asserted, that Biden won’t live out a second term, so a vote for him is a vote for Vice President Kamala Harris—an echo of Stevenson’s charge that a vote for Ike was a vote to make Vice President Nixon commander-in-chief.

Polling suggests age is a potent avenue for attack. A recent analysis by the Washington Post’s Aaron Blake argues that Biden isn’t just facing an age issue but a “perceived mental-sharpness problem, and the gap between him and former president Donald Trump on such questions has also expanded.” While Blake stops short of concluding it’s politically fatal, he cautions: “The problem is that the margins are just so fine, and this issue presents the vast majority of voters with a historically unusual liability, however compelling they might ultimately find it, to balance against Trump’s liabilities.”

Without question, we have several historically unusual factors. Biden is our first octogenarian president (although life expectancy is much higher than in the 19th century, and for 80-year-old white males, average life expectancy is another 7.8 years.) Biden also has to perform in a 24-7 media culture, so visible aspects of aging, such as his more prevalent stammer, can’t be hidden. Age will be an X-factor of unknown relevance until the votes are tallied.

But it is also true that almost every time there is an age gap between the candidates, the younger candidate’s campaign tries to exploit it. And in each of those instances, age was not the factor that determined the outcome.

Even today, we don’t have any firm evidence that concerns about Biden’s age are turning Democratic voters into Republican voters. Any softness in Biden’s level of support is more easily attributable to the lingering effects of high, albeit cooling, inflation, though it is difficult to separate the impact of age and inflation on Biden’s numbers.

After The Wall Street Journal polled voters on their concerns regarding age and mental fitness, it followed up with a North Carolina Democrat who wished there was another option for her party’s nominee. She said, “It’s 100% because of his age. He’s done a great job. He’s good right now. But somebody at the age of 80 has a high risk of things going wrong physically and mentally.” But when asked if the choice is Biden or Trump, she was clear: “I can’t say it strongly enough, absolutely Biden.”

That’s just one anecdote, but the logic is sound. If you are satisfied with the incumbent’s record, you will almost certainly stick with the incumbent.

Sure, it would be helpful to Biden’s cause if he spoke more crisply and put to rest any concerns about his fitness. But what Biden needs most is continued declining inflation, increasing real wages and disposable personal income, low unemployment, and solid economic growth so more voters will be satisfied with his record on Election Day.