In 2016, when Adrian Fontes became the first Democrat in a half century to oversee elections in Maricopa County, Arizona—a giant jurisdiction with more voters than two dozen states—he had no idea what he was in for.

Over the course of the next four years as county recorder, the former Marine and prosecutor would spearhead a project to mail a ballot to every registered voter, navigate a global pandemic, and face down a mob of Donald Trump’s supporters, who had convened, guns in tow, outside of the county’s election headquarters in 2020 after Fox News called the state for Joe Biden. At one point, when conspiracists, including InfoWars’s Alex Jones, began attacking Fontes by name, he and his wife packed “go bags” and briefly evacuated their children from their home.

But if those years were bracing, Fontes, who became Arizona’s secretary of state earlier this year, is not cowed. If anything, his experience on the chaotic front lines of election management has underscored his long-standing belief that the best way to revive public confidence in elections in this age of distrust is by embracing a position of radical transparency.

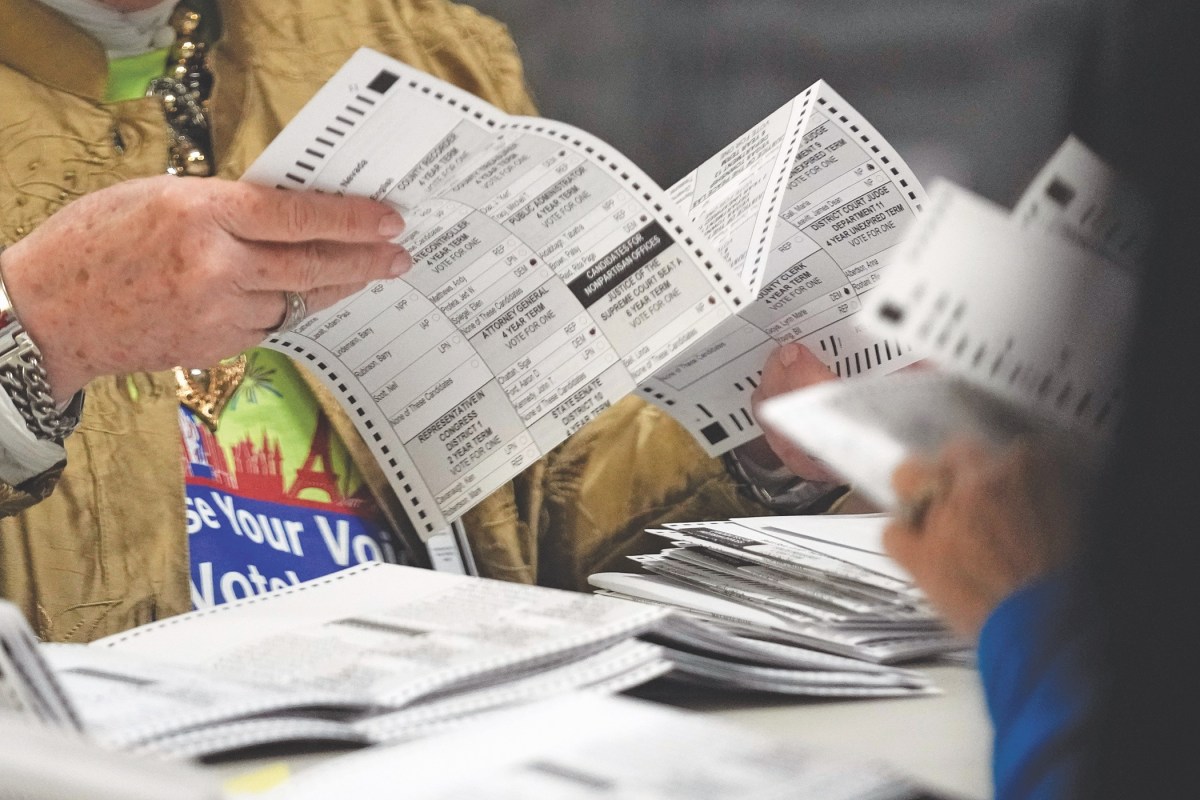

One of Fontes’s most revolutionary policy pursuits is straightforward: He believes that in every election, during the most disinformation-prone stage—immediately after the votes are counted but before the winner has been certified—election officials should publish digital images of every ballot cast. Those images should be uploaded in a form that’s easy to read and sort, so rival campaigns, grassroots groups, press outlets, academics, and individual citizens could judge the results of an election for themselves, rather than having to rely on an official’s word. Those who continued to spout groundless theories of malfeasance or fraud could also then be checked by other outside groups and individuals with direct access to the same ballot images.

“[Ballot images are] where we actually glean the data that gives us the results,” Fontes told me last spring. He explained that most voters nationwide hand-mark paper ballots; officials then use scanners to create digital images of those paper ballots, then employ software to count votes and detect inconsistencies. Sharing those digital ballot images as widely as possible is the best way to illustrate how officials arrive at a final count, he said. “There is no better tool. It doesn’t exist.”

A handful of counties, including Dane County, Wisconsin, where the state capital, Madison, is located, and San Francisco, have already implemented this audacious idea. Election officials in both counties say the move has improved voter confidence. Other states, including Maryland and parts of Florida, have been using ballot images in recent years to verify results before certifying winners. Officials there, too, say the practice has helped cool political temperatures, especially when a losing campaign can scrutinize the images itself, and therefore determine, in a matter of hours, how many ballots are contestable and whether a recount or litigation would be fruitful.

Making ballot images publicly available, Fontes argues, is also relatively simple technologically, thanks to recent changes in election infrastructure and procedures. After Russian attempts to hack the 2016 election, municipal and state governments purchased new voting systems for polling places that produce a paper record, while the coronavirus pandemic led to a vast expansion of voting by mail. As a result, nearly all ballots today are on paper—either hand-marked directly by voters or printed out by voting machines. Scanning those paper ballots, then publishing the images in a user-friendly form online, isn’t rocket science.

But if Fontes, along with a growing group of Republican election officials who deal day to day with election deniers, see public ballot images as a policy no-brainer, the idea has faced strong headwinds in state legislatures. Progressives argue that making ballot images public could compromise voter anonymity and invite violence on individuals. They also say the images could be hacked, further compromising public trust. Meanwhile, county election managers of both parties worry that this and other transparency reforms could create an outsized burden on their operations, which already must function under tight deadlines and shoestring budgets.

The biggest critique of this idea, however, is philosophical. Many argue that presenting the public with evidence of this kind is pointless. The tin-hatted Big Lie conspiracists are not interested in evidence at all, the argument goes—much less evidence produced by the same government officials they accuse of engaging in vast and convoluted conspiracies. And these propagandists wield enough influence already: Nearly 70 percent of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents were still telling pollsters, in July 2023, that Joe Biden was not legitimately elected.

But Fontes and his allies say that critique misses the mark. The point of making ballot images public is not to convince the die-hard Trumpers, says Ken Bennett, a mild-mannered Republican Arizona state senator and former secretary of state, who sponsored state legislation in 2023 to make ballot images public. It is, instead, to empower those rank-and-file conservatives who have been conditioned to distrust elections but are open to believing otherwise if given persuasive proof. Such voters exist, Fontes and Bennett argue, and perhaps in considerable numbers. The share of Republicans who believe there’s “solid evidence” proving that Joe Biden didn’t win the 2020 election has fallen in the past two years, according to a March CNN/SSRS poll. The Republican pollster Sarah Longwell, who publishes The Bulwark, says the “move on from Trump” bloc comprises 30 percent of the GOP—a group sizeable enough to swing competitive races.

Bennett, who is Fontes’s key Republican partner on this issue in Arizona, told fellow lawmakers earlier this year that while making ballot images public won’t solve the problem of distrust in elections, it’s a crucial start. “We’ve got to do something,” he said in an Arizona senate hearing in March. “If we want a different result, I think we have to do something different than what exists right now.”

Fontes was having a drink after a conference for state and local election officials in January 2017 when he first heard about giving the public access to images of every ballot cast. Fontes, then the newly elected Maricopa County recorder, was talking to a former state election director and UN election observer, who was praising, of all places, Mongolia. The man was saying, Fontes recalled, that in Mongolia 98 percent of voters report very high confidence in the outcome of their elections. Fontes asked the guy what the country’s trick was. “He said, ‘Well, this place actually publishes their ballots online, by precinct, so that the population can go count it their doggone selves,’ ” Fontes said.

Fontes was gobsmacked. When he got home, he began researching and found that, unlike most election records, which are kept in databases, spreadsheets, or coded computer logs, ballot images are visceral documents that reflect human errors—like errant pen marks or smears, or when someone circles an oval rather than filling it in. But voters almost never see such documents; they only hear the results on the nightly news, which seem to have emerged by some unknown process performed by shadowy forces elsewhere. To most voters, the logistics of how ballots are counted are, at best, opaque. So the idea of taking a page out of Mongolia’s book, and letting voters in on the ground level—inviting them to examine, sort, and scrutinize the same ballot images that election officials are using—seemed like an “incredibly powerful” idea, Fontes said. “We’ve gotten to a place where I think it’s high time that we have that public verifiability.”

This push toward radical transparency represents a sea change for U.S. election management. For most of the last century, officials have simply asked citizens to trust that a count is correct, that the systems in place were credible. That era is over, Fontes said. Public trust in government institutions is now at a near-historic low; just 20 percent of Americans say they’re very confident in the country’s elections, according to a January 2022 ABC/Ipsos poll. The modern American public needs more proof, Fontes said, and ballot images are the key. “The principle that a person can walk into a county treasurer’s office and ask for the budget and be shown where the money from the county is actually being spent is almost exactly the same,” Fontes said. “Except that this is actually better, because this is the real representation. It’s as if you walked into the county treasurer’s office and got copies of all of the canceled checks.”

Ballot images should be uploaded in a form that’s easy to read and sort, so rival campaigns, grassroots groups, press outlets, academics, and individual citizens could judge the results of an election for themselves.

A few years ago, I saw up close how this works in practice. In 2018, I was in Leon County, Florida, home to Tallahassee, when election workers were performing the recount of what turned out to be a contentious election involving three statewide races, including the races for governor and U.S. Senate. Before the recount process began, Mark Earley, the elected supervisor of elections, and a Democrat, asked the representatives of the candidates and parties to follow him to his computer. He showed them a new election audit technology that he wished he could use in the recount—but was not officially approved. The tool was from Clear Ballot, a company founded by Larry Moore, that a handful of Florida counties were using as part of a pilot program. Clear Ballot’s technology rescans every paper ballot cast in an election to create digital ballot images, then analyzes the ink and white space inside each marked oval and ranks the sloppiest, and therefore most contestable, ovals in each race. Election workers—that is, humans—then scrutinize each of those messy ballots individually to determine a voter’s intent, and to find and fix any mistakes made by the official voting system.

“I went through this four times that day and said, ‘After we go through this official process for an entire week, here’s what you’re going to see,’ ” Earley told me. He showed the representatives images of the most messily marked ballots in each race to illustrate what the ensuing manual recount would likely look like. “They were thrilled to be able to see it so transparently from a different system,” he said.

While Earley’s team could only use Clear Ballot’s technology informally—the state had not yet approved image-based recounts and audits—it was clear that the software changed the game. “The fact that you could search through all of these images so quickly and find where there were not votes, or overvotes [more than one ink mark], or where voter intent was misinterpreted by a machine” was transformational, Earley said. “If there’s a mistake, it’s right there. It’s apparent. Nobody’s hiding anything. It’s so easy to understand.”

A couple years later, another effort, led by the San Diego County–based progressive nonprofit Citizens’ Oversight, used ballot images and its technology, Audit Engine, to verify the results of the 2020 contest in central Florida’s Volusia County, where Trump had won by 14 points. Lisa Lewis, Volusia County’s supervisor of elections, who is a Republican, told me she invited the scrutiny. “We were able to tell people, ‘Look, we didn’t do an audit. It was an independent auditor. And the results are the results,’ ” Lewis said. “There are always going to be people who are skeptical about the election … But it does relieve a lot of people’s [minds]. The ballot speaks for itself.”

Since 2016, Maryland has been the first and only state to use images to verify the results of every contest before certifying the results. Elsewhere, the use of ballot images is slowly increasing behind the scenes. Voters hand-mark their ballots in two-thirds of the country’s jurisdictions, and the latest software allows election workers to review digital images to double-check, correct, or reject votes—which some jurisdictions now do. (Partisan observers are usually present.)

In 2020, Florida passed a law allowing officials to use ballot images for recounts, thanks in part to Earley and his Republican colleagues’ enthusiasm about the idea. But opposition within the state bureaucracy to Clear Ballot’s monopoly as the only state-certified ballot image technology has meant that it will not be in place for the 2024 election. Transparency activists and Florida’s Democratic Party also have sued to save the images, as the new recount law didn’t make preserving the images mandatory.

The ongoing state-level debate over whether to make ballot images public is rarely covered by national media outlets, but the fights are heating up as more jurisdictions hire Clear Ballot. If Fontes and Bennett get their way, Arizona will be next.

Earlier this year, Fontes, in his new position as Arizona’s secretary of state, and Bennett, who was reelected as state senator in 2022 after nearly 15 years out of office, emerged as a powerful but unlikely duo on Arizona’s public stage. Fontes, a Democrat, is pugnacious and blunt (he calls election deniers “MAGA fascists”), while Bennett, a conservative Republican, is soft-spoken and conciliatory. But the men are bound by their shared belief that ballot images must be made publicly available statewide.

Bennett first heard about the idea a few years after Fontes. It was the spring of 2021 and Arizona was in the throes of an ugly battle over the results of the 2020 election. Bennett was not in public office at the time, but the state senate had asked him to be its liaison at the Cyber Ninjas’ audit of Maricopa County’s ballots. It was there that Bennett met John Brakey, a gregarious progressive transparency activist from Tucson, whom the Ninjas had allowed to observe, to claim bipartisanship. Bennett and Brakey soon bonded over the idea of making ballot images public and together pushed Cyber Ninjas CEO Doug Logan to employ them as a tool in the audit. Bennett went so far as to promise Logan that a GOP donor would pay for a ballot image review if he agreed to it. (Logan demurred, but he eventually gave a contract to an election denier who never finished the audit.)

Bennett emerged from the experience a fervent convert to the idea of radical transparency, and, upon taking office in January 2023, he drafted a bill—his office’s top priority—to make public four sets of election records immediately after Election Day: registered voters; people who voted; digital ballot images; and cast-vote record. Fontes immediately threw his support behind the bill. But opposition came fast and furious. Progressive advocates argued that making voter lists and ballot images public could be dangerous, especially in primary elections in small precincts, where someone could link a ballot to an individual, thus compromising a voter’s privacy and right to a secret ballot, and possibly exposing them to right-wing vigilantes. “Bad actors could easily abuse this data,” Alex Gulotta, Arizona state director of All Voting is Local Action, and Jenny Guzman, program director of Common Cause Arizona, wrote in an Arizona Republic commentary.

Bennett, Fontes, and other supporters scrambled to address the critics’ objections, pointing out that reams of voter information are publicly available. Political parties and campaigns already have access to lists of registered voters, as well as who voted—data they use to turn out voters. Bennett also agreed to reduce the bill’s scope to protect voters’ identities in low-traffic precincts, while Brakey tried to persuade his fellow progressives, including Gulotta and Guzman. It was tough going.

Nearly all ballots today are on paper—either hand-marked directly by voters or printed out by voting machines. Scanning those paper ballots, then publishing the images in a user-friendly form online, isn’t rocket science.

Experts in academic and advocacy circles, many of whom have long opposed anything electronic in the vote-counting process, worried that ballot images could be hacked. Practicing election officials, including Earley, pushed back against those concerns. Forging hundreds—and sometimes thousands—of ballot styles, which change in every jurisdiction to reflect local races, would be an extraordinarily complex undertaking, and any attempt to do so on a large scale would likely be detected by security protocols, he explained. There is also no evidence of any statewide or federal election ever having been hacked in this way.

Other critics’ concerns were logistical. Figuring out how to publish ballot images online in a user-friendly format would require technological investment. After all, simply uploading tens of thousands of JPEGs wouldn’t do the trick. To be persuaded, nontechnical people would need to be able to sift through ballots and compare what they saw to a final tally. To that end, state officials would need to either build new software in-house for local jurisdictions or contract with an election systems firm.

Still others objected to Bennett’s bill on premise: More public data, they argued, would not only fail to convince post-truthers enthralled by Trump’s Big Lie, it could also potentially fuel more propaganda and frivolous litigation. They rejected Bennett’s theory of change—that sizeable numbers of non-Trump Republicans wanted to see the evidence for themselves.

After a contentious, 15-week battle, in mid-May, Bennett’s bill passed on partisan lines, but four days later it was dead. Democratic Governor Katie Hobbs, who had been Fontes’s predecessor as secretary of state, vetoed it, citing many of the progressives’ concerns.

Fontes and Bennett were disappointed but resolute. Bennett told me he plans to introduce a new version of the bill first thing in the 2024 session, this time addressing some of his critics’ primary fears head on. The new bill will apply only to general elections, where everybody is voting on an identical ballot, so there would be no way to identify a specific person in a precinct. And it will give counties the option to decide whether to release ballot images. “So if Pima County doesn’t want to do it, but Maricopa and Yavapai do, fine,” Bennett said. Maricopa County, with nearly two-thirds of Arizona’s voters, is already on board with the new version of his bill, he added.

Fontes too remains committed to the legislation, echoing a growing number of election officials nationwide. “We don’t have publicly verifiable elections if we don’t have those images out there,” he warned. In an age of widespread public distrust, it’s radical transparency or bust.