Not so long ago, John Roberts patiently explained to reform-minded folk on Capitol Hill that the Supreme Court had no need for an ethics code. It was December 2011, and despite a recent scandal involving unreported income for Clarence Thomas’s wife, Roberts assured in his year-end report to Congress that the justices were policing themselves just fine. They followed laws that required them to report major gifts (Thomas’s lapse aside, presumably), and they used the lower-court code of conduct as “guidance,” even though it wasn’t binding. In some places, the chief justice seemed to hint that outside pressure over ethics was not only unnecessary but actually harmful—for instance, if it forced a justice to recuse himself “as a matter of convenience or simply to avoid controversy.” “At the end of the day, no compilation of ethical rules can guarantee integrity,” Roberts tutted.

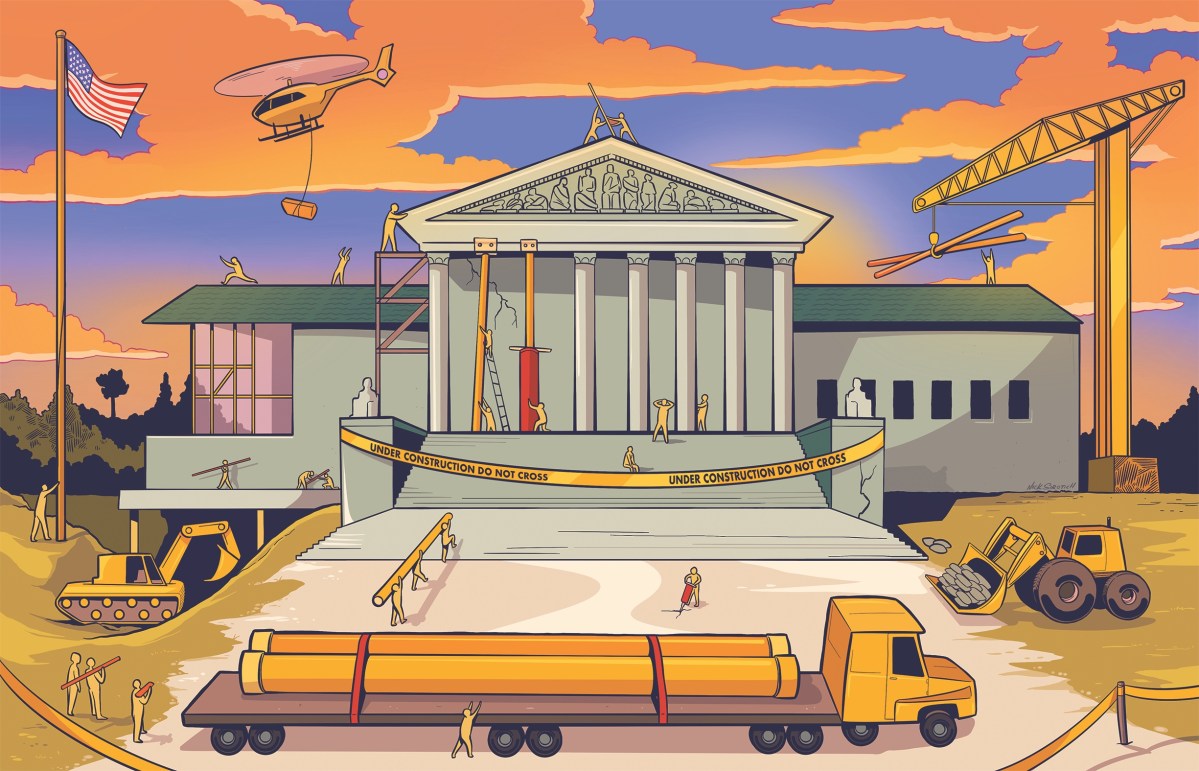

This fall, the chief justice ate his words. Faced with press exposés of ethical misconduct, especially by Thomas—free luxury vacations and private-school tuition from the billionaire Republican megadonor Harlan Crow, among many other unreported gifts—as well as plummeting public opinion, a congressional investigation, and the possibility of direct oversight from lawmakers, Roberts adopted the first ethics code in the Court’s 235-year history. The rules contained no enforcement mechanism and were watered down in subtle ways from the standard that lower courts follow. Still, it was an extraordinary capitulation: The justices had done something they long insisted they would never do.

On MSBNC, Rhode Island Senator Sheldon Whitehouse proclaimed the code “the first chink in the armor of indifference” around financial misconduct on the bench. But it was much more than that. The justices’ willingness to place specific limits on their own behavior—however unenforceable—marked a blow to an even more fundamental belief that the Court has long held about itself: its singularity.

For the Court to remain “supreme,” the idea goes, it must float serene above all external influence, including any kind of ethics oversight or congressional regulation. In his 2011 report, Chief Justice Roberts took care to note that the justices observed federal financial disclosure law even though “the Court has never addressed whether Congress may impose those requirements on the Supreme Court.” And again, on the justices’ decision to follow federal law relating to recusal: “The limits of Congress’s power to require recusal have never been tested.” This past summer, Justice Samuel Alito—whose own ethical lapses have also come to light, including an unreported luxury jet trip to Alaska courtesy of another GOP donor with business before the Court—scoffed at the prospect of congressional intervention, telling The Wall Street Journal, “No provision in the Constitution gives them the authority to regulate the Supreme Court—period.” Alito wasn’t speaking out of turn; he was articulating long-held policy. Simply put: The Court must stand alone.

There is, however, a danger in always standing apart from others. It can easily lead to standing above them. As Garrett Epps, the Washington Monthly’s legal editor, wrote in fall 2022, the Court is now mired in its third great historical crisis. Twice before, in the 1850s and the 1930s, the high court has been captured by adherents of one political party who have attempted to govern from the bench. When one branch of government declares its own primacy over the others, as well as the American people, the result is dangerous instability. In the era of Dred Scott, the Taney Court sided firmly with southern slaveholders, accelerating the coming civil war. During the Great Depression, the “Four Horsemen” on the Hughes Court blocked government programs meant to lift the country out of economic disaster.

Now we have the Roberts Court, shaped by pro-corporate ideology and conservative resentment over social and demographic change. Overturning decades of precedent, the conservative supermajority has issued ruling after ruling that undermines the ability of executive branch agencies to regulate industry, to fight climate change, and to protect consumer health and safety. Its 2022 Dobbs decision on abortion has created a dystopian reality on the ground: neighbors informing on neighbors, children forced to give birth to their rapists’ babies, terrified doctors waiting for patients to get sicker before performing medically necessary procedures.

The good news is that the reactionary turn of the Court has awakened a sleeping giant. Voters, including many Republicans, are in open revolt against Dobbs, as recent elections demonstrate. A popular movement against the Supreme Court itself hasn’t coalesced, at least not yet. But the justices’ actions have increasingly shocked center-left elites out of their ingrained deference toward the Court—as the pressure for ethics reform that congressional Democrats and others put on Roberts shows.

And in the end, Roberts blinked. Modest as it was, the Court’s concession—that it is not inviolable, not, after all, so supreme—indicates that the justices may finally have gone too far, and cracked open a window for deeper reform.

Today’s progressives now realize that the high court is not an infallible fount of wisdom, and that it is historically more often a conservative force; and with that understanding comes a question that these scholars will help answer: What is the Supreme Court even for?

Anyone concerned about the Supreme Court today should be working to prise that window open further. And to do so, they ought to draw on the robust and inventive debate that is brewing among scholars in law schools, think tanks, and advocacy organizations over how to fix the Court. Some of their ideas are bold structural changes: dividing the Court into rotating panels, stripping it of jurisdiction over certain issues, or controlling its certification process. Others are practical and based on policies already proven to work elsewhere, such as creating a “Congressional Review Act” for Supreme Court decisions, as already exists for executive branch regulations. What these ideas share is a recognition that the rights-giving 20th-century Court that liberals came to respect, even revere, is gone. Today’s progressives now realize that the high court is not an infallible fount of wisdom, and that it is historically more often a conservative force; and with that understanding comes a question that these scholars will help us all to answer: What is the Supreme Court even for?

President Joe Biden and other Democratic leaders have not embraced this deeper reform debate, perhaps recognizing that the political moment hasn’t yet arrived. When the survival of democracy depends on each coming election, a little short-term thinking is understandable.

But one day that moment will come, and it may come suddenly: a wave election, a string of Senate vacancies, a scandal of new, earth-shattering magnitude, or a series of decisions as harmful as Dobbs. When that happens, reformers need to have a plan ready to go—a plan that will require broad public consensus about what problems need to be solved (Should we be restoring the Court’s legitimacy? Limiting its power? Or some combination of both?) and a detailed road map to achieve those goals through nitty-gritty policy. And it’s not as simple as drafting up a document and leaving it on the shelf. Being ready means spending years on movement building to bring together academics, policy wonks, and regular Americans, all waiting to grasp that perhaps fleeting and unforeseeable opportunity. Either that, or submit to being governed for another 30, 40, or 50 years by unelected partisans in robes.

So, for those who want to save the Supreme Court, that conversation must begin now.

A vanguard of law scholars has long warned that Americans, and liberals in particular, rely too much on the courts as interpreters of the Constitution and defenders of civil rights. Even as the Supreme Court recognized gay marriage in the 2010s, building on the unenumerated rights it had discovered in previous decades, “popular constitutionalists” such as Mark Tushnet and Larry Kramer worried that the bench was grabbing power for itself—power that could just as well be used to take rights away. With the blockade of Merrick Garland and the election of Donald Trump, those fears were realized. A tipping point for many law scholars came during the raucous and sometimes absurd confirmation of Brett Kavanaugh, in which the nominee, who had been accused of sexual assault, ranted about Clinton plots and his love for beer.

Watching those hearings, Ganesh Sitaraman, a constitutional law professor at Vanderbilt, had had enough. He went to a colleague, Daniel Epps of Washington University in St. Louis, who recalls him saying, “This is not going to go away. People are going to care about this. Let’s get on top of this.” In 2019, the pair published a law review article titled “How to Save the Supreme Court.” (Dan Epps is the son of Garrett Epps, who helped to edit this Monthly article.) The scholars painted a dire picture. The partisan balance and public image of today’s Court, they said, is roughly equivalent to that of the pre–Civil War Taney Court. The similarity lies not in the overt racism of decisions like Dred Scott, but rather in the widespread public belief that the Court was in the tank for southern slaveholders. Today, the Court is viewed by many as an arm of the Republican Party, a source of grave concern to Epps and Sitaraman: “In a world where the Supreme Court is widely seen as just another political institution, how will people think about law itself? Our fear is that in such a world, the very idea of law as an enterprise separate from politics will evaporate.”

The Supreme Court needs to be thought of as a neutral arbiter for political disputes, not just another player in them, the law professors argued—and so fixing it today is a question of restoring that aura of public trust. Right away, that goal disqualified the most talked-about idea at the time: court packing. Supporters of court packing like the political scientist Aaron Belkin argue that the Supreme Court has already been stacked with highly ideological conservatives who gained their seats through norm-breaking political brinksmanship, and so to add, say, six liberal or moderate justices would actually be to unpack it. But as Epps and Sitaraman pointed out, that reasoning would mean little to Republicans, who would have every incentive to repack the Court as soon as they regained power. (Belkin, for one, finds that argument unconvincing. “The first thing is that the Court has already been stolen. If your wallet is stolen, you don’t forgo efforts to recover it just because it might be stolen again,” he told The Atlantic in 2020.)

To fix the Court in a durable way, the two scholars imagined a total rework meant to make partisan capture almost impossible. The first step was to expand it even more. Epps and Sitaraman proposed appointing every circuit court judge—all 179 of them—an associate justice of the Supreme Court, which would hear cases on a rotating panel system. Every two weeks, nine justices would be picked by lottery from the larger pool. A few more tweaks would ensure impartial rulings: No more than five judges on a panel could be appointed by a president of the same party, and to rule federal law unconstitutional would require a 6–3 supermajority. Each change was meant to counteract a structural weakness that makes the Court vulnerable to political machinations. Partisans in Congress, for instance, would have less incentive to game the appointment process if each seat mattered less, and the larger pool of judges would reduce the unpredictability of death and strategic retirement.

Along with that framework, which Epps and Sitaraman call the “Supreme Court Lottery,” they offered an alternative: the “Balanced Bench.” In this variation, five permanent justices from each party select another five temporary justices, who must be chosen either unanimously or by a supermajority. Those temporary judges serve a year on the Court, and are chosen two years in advance (so that no conniving parties can strike deals with to-be-appointed justices on specific upcoming cases). If the Court doesn’t fill those seats, it doesn’t convene. Like the other plan, the Balanced Bench is designed to thwart partisan takeover; in this case, by incentivizing consensus. Permanent justices would be forced to choose the most moderate and broadly acceptable temporary justices; and Congress would be encouraged to appoint more plausible centrists to the lower federal judiciary, since ideologues would have little chance of reaching the high court.

Epps and Sitaraman’s institutionalist, fix-it attitude defines one side of a central divide in the reform debate. You might call their approach the “legitimacy” school of reform, the one that holds that we need to restore respect and trust in the Court. The other side—call it the “democratic” or “disempowering” school—emerged in a lengthy, at times fiery reply to Epps and Sitaraman in the California Law Review. The authors, Harvard’s Ryan Doerfler and Yale’s Samuel Moyn, offered a much simpler plan for the Court: Get it out of the way. “Asking ‘how to save the Supreme Court’ is asking the wrong question,” they wrote. “Saving the Supreme Court is not a desirable goal; getting it out of the way of progressive reform is.”

Doerfler and Moyn, who write in long, elliptical sentences that land like academic grenades, diagnosed a liberal myopia about courts that traces back to Franklin Delano Roosevelt. They argued that the 32nd president’s challenge to the Supreme Court was disastrous—not because he proposed a court-packing scheme, but because he failed. The story of the famous “Switch in Time” and the narrow defeat of court packing in the Senate is often treated as an example of presidential overreach, a reason why the Court should be off-limits. But in fact, after Roosevelt accepted judicial deference in lieu of real structural change, the events that followed—the Court’s wartime decisions on religious freedom, the rights-expanding precedents of future decades, the anti-regulation rulings of the 2000s—saw the institution grasp ever more power. Meanwhile, liberals got the policies they wanted, but were lulled into relying on courts for those things rather than fighting for them themselves.

To Doerfler and Moyn, tinkering changes like those offered by Epps and Sitaraman fall prey to that liberal Court Adoration Syndrome. The Epps/Sitaraman approach claims to protect the Court’s neutrality, but really, in balancing partisan interests so overtly, it’s just replacing left- or right-wing ideology with a different, centrist point of view. Beyond that, it doesn’t address the fundamental problem of the Court’s outsized influence. But the most immediate obstacle to these technocratic reforms, Doerfler and Moyn said, is that they are too complex for the average person to grasp and to chant for at a political rally. “This dooms any case for their feasibility,” they wrote. “What only law professors can understand, a popular movement will never demand.”

The only response to a Court that has grabbed too much power, they said, is to take some of it away. One way to do that would be to strip it of jurisdiction over subject areas in which it might feel tempted to interfere with progressive change, such as environmental regulation or health care reform. The Constitution gives the Supreme Court “original jurisdiction” over disputes between the states and between high-ranking ministers such as ambassadors. That can’t be taken away. Everything else falls under appellate jurisdiction, which Congress has the constitutional power to regulate. Doerfler and Moyn didn’t outline a definite plan for how jurisdiction stripping should take place; the point, they said, is for the people themselves to decide how the country should be run, and to clear a path through obstructive courts to put those values into action. Other “disempowering” tools can be part of that conversation: “override” provisions that would allow Congress to vote to nullify Supreme Court decisions, or “poison pills” that would trigger more drastic policies if the Court overturned legislation (though Doerfler and Moyn are skeptical about the power of this deterrent).

“In a world where the Supreme Court is widely seen as just another political institution, how will people think about law itself? Our fear is that in such a world, the very idea of law as an enterprise separate from politics will evaporate,” the scholars worried.

Epps and Sitaraman soon fired back—you can’t just blow up the Court, they said; you need it for some things, like rights protection—which kicked off a lively discussion in the nation’s law journals, with ideas flowing from all corners of the country. Conservatives joined the discussion too, including William Baude, who continued to call for reform of the “shadow docket,” a term he coined in 2015 to describe emergency orders, which the Roberts Court has increasingly used to decide cases without a full hearing. One of the more creative examples came from Suzanna Sherry of Vanderbilt, who in “Our Kardashian Court” argued (while missing a golden opportunity to spell it “Kourt”) that the justices have bought into the celebrity culture exemplified by the famous-for-being-famous family. Cults of personality form around the Court’s biggest stars, whose jurisprudence has become warped by the need to cater to their fan bases. Think of the “Notorious RBG” mugs, of Antonin Scalia’s rock star tours of law schools, and of the many openly political events attended by Alito, Neil Gorsuch, and Amy Coney Barrett, including campaign-style pressers with Mitch McConnell and glitzy Federalist Society galas. To solve the problem, Sherry proposed making authorship of opinions secret and prohibiting separate concurrences and dissents. To avoid sounding like the Real Justices of First Street, the bench must speak in one disembodied voice.

Many of these reforms may sound extreme in their ambition and their scale. Court packing, jurisdiction stripping, elevating a hundred district judges at once to the Supreme Court—ideas that sweeping evoke the antidemocratic judicial takeovers of Hungary’s Viktor Orbán or Poland’s Law and Justice party. But almost all of the proposals have precedent in America’s history, and helped to shape the basic structure of the Court as well as the changing intellectual paradigms that guided its jurisprudence.

In 1801, John Adams shrank the Supreme Court by one seat (from six to five) and packed the lower federal judiciary just before handing over the presidency to his rival, Thomas Jefferson. This “Midnight Judges Act” sparked a cutthroat fight in Congress, and it inspired Chief Justice John Marshall to get in while the power grabbing was good: Two years later, he used a case stemming from Adams’s appointments, Marbury v. Madison, to establish the practice of judicial review, a privilege not explicitly afforded to the Court in the Constitution. The size of the Supreme Court would change six more times in the next 80 years, often for political reasons. (Abraham Lincoln, who battled the Court over his Civil War powers, expanded it to 10 justices in 1863.)

The Georgetown conference had an air of action and invention, in sharp contrast to the glum “what-can-you-do” coverage that followed Dobbs. Unlike other places of public discourse, there was a willingness to directly confront the Court, and even to take action against the justices themselves.

The same goes for other present-day reforms. Jurisdiction stripping as a check on the judiciary was endorsed by Progressive Era politicians who sought to shield child labor regulations from a hostile Court that had twice struck them down; the same senators, including Robert La Follette of Wisconsin, also called for supermajority requirements and legislative override provisions. Later that century, southern segregationists outraged by Brown v. Board of Education called on the Senate to make itself the final appellate body on questions of states’ rights, with the power to overrule the Supreme Court.

As Jamelle Bouie of The New York Times once pointed out, the historical norm has been to treat the Supreme Court as just another democratically accountable institution—a work in progress, not an untouchable holy idol. “This idea, that the court should work with our democratic aspirations and not against them—and that we should not hesitate to change and experiment with the court should we find ourselves struggling against it—is practically verboten among mainstream politicians,” he wrote in 2021. “But it is a critical part of our political heritage, stretching back to President Thomas Jefferson’s battles with a Federalist-dominated judiciary at the start of the 19th century.”

As the Democratic presidential primaries began to heat up in 2020, the academic discussion seeped into progressive politics. Sitaraman had a long association with one of the front-runners, Elizabeth Warren, having served as her policy adviser and legal counsel in different stints since 2008. Now the wonkish senator began to repeat some of his ideas on the campaign trail. Senator Bernie Sanders of Vermont disavowed expanding the Supreme Court but supported a plan to rotate conservative justices down to lower courts. The policy nerd and upstart mayor Pete Buttigieg joined in, enthusiastically endorsing the Epps/Sitaraman lottery and citing The Yale Law Journal in his stump speeches. The demand among the base was strong enough to force Joe Biden to flirt with reform as well; as a candidate, he refused to say that he wouldn’t pack the Court.

Playing footsie with FDR’s legacy didn’t cost Biden the election, though it was vanishingly close in key swing states. With a razor-thin majority for Democrats in Congress, a total overhaul of the Supreme Court in 2021 was obviously out of the question. But Biden did what seemed like the next best thing: He formed a presidential commission, stacked it with the country’s finest minds in constitutional law, and told them to report back on the present-day debate, the history of court reform, and the feasibility of the myriad ideas floating around. It might have been the start of a much-needed conversation, a chance to awaken the public to the crisis of the Court and hand them the intellectual tools needed to one day fix it.

In the end, it wasn’t. The scholars did their job well, assembling a 300-page report that drew together all the major ideas and the arguments for and against. They compared the Epps/Sitaraman proposals and the competing policies from Doerfler and Moyn—and many others—and they plumbed how those tied in to differing philosophies about the role of the Court. They collected dozens of hours and thousands of pages of testimony from even more experts. Reading the commission’s report, which was released in December 2021, is enough by itself to give a layperson a comprehensive understanding of the debate. But it doesn’t offer any guidance about what to do next—and that’s because the scholars were told not to. Michael Waldman, a member of the commission and the president of NYU Law’s Brennan Center for Justice, recently aired his frustration with this on the popular podcast Strict Scrutiny: “We were actually instructed, publicly instructed, not to reach conclusions. And we didn’t—and so this was finally a government agency that works as intended.”

By the end of 2021, the political momentum had petered out. The White House had moved on to other massively consequential programs, like the $1 trillion infrastructure bill and the Build Back Better initiative. The latter took almost a whole year of intense negotiations to get Senator Joe Manchin’s crucial signoff for its successor, the Inflation Reduction Act. All the same, some commentators were still working to bring a richer court reform discussion to the broader public. Journalists such as the Times’s Bouie, Vox’s Ian Millhiser, and The Washington Post’s Ruth Marcus tracked the Court’s outrages and the potential structural changes worth considering. Week by week on Strict Scrutiny, the law professors Leah Litman, Kate Shaw, and Melissa Murray gave in-depth and accessible explanations of the Court’s latest doings, while helping listeners to laugh through the absurdity and the horror. The reformers themselves occasionally got the word out through scattered opinion pieces in mainstream news.

Yet reform remained sidelined. Part of the problem seemed to be that the conservative supermajority hadn’t yet realized people’s deepest fears. Despite flirting with initiatives like the “independent state legislature” theory and a Texas abortion law designed to avoid judicial review, the Court did not embrace the most extreme options available to it, preferring instead its usual fare of striking down government regulations and protecting the rights of corporations and the religious. The runaway Court remained a worry, but a worry in the back of the public’s mind.

In summer 2022, a case out of Mississippi would change all of that.

The first thing to note about Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization is that, from a strategic standpoint, it was totally unnecessary. The Supreme Court didn’t need to overturn Roe v. Wade to effectively outlaw abortion in red states. As observers noted before the decision, the Court had been chipping away at the precedent for years by allowing ever more onerous requirements on abortion providers. It could have continued to do so, leaving Roe standing in name only and producing a much more muted backlash. But Mississippi passed a law directly challenging the precedent, and the conservative Fifth Circuit (a panel even more partisan and unmoored from convention than today’s Supreme Court) struck it down, citing Roe, setting up a confrontation the justices couldn’t resist.

Assigned to write the opinion, Alito, a devout Catholic and avowed enemy of Roe, decided to swing for the fences. The irascible originalist dynamited 50 years of bedrock precedent, declaring Roe “egregiously wrong” and “and on a collision course with the Constitution from the day it was decided.” To prove that abortion has always been a “crime,” he cited a 13th-century jurist, Henry de Bracton, who was an authority on the ducking stool and who called for women suspected of false pregnancy to be locked in a castle and examined daily by “feeling her breasts and abdomen and in every way.” Even worse, Alito appeared to make no exception for rape or incest. And he gave the sense in his writing that the conservative supermajority was drawing a new line in the sand. From that point on, the possibility loomed that they might declare any long-standing precedent unconstitutional, as long as they judged it, by whatever standards suited them, “egregiously wrong.”

Justice Thomas’s concurrence gave a hint of where that could lead. Many of the rights enshrined by the Warren and early Roberts Courts over the past half century—including abortion—relied on an unenumerated “right to privacy” discovered within the Fourteenth Amendment. Now, Thomas opined, the Court ought to follow up on its rollback of Roe by declaring other privacy-based rights unfounded: the right to use contraception, and the right to be intimate with a person of the same sex or to marry them. (Notably, he did not mention Loving v. Virginia, the decision that struck down anti-miscegenation laws. Thomas is Black, and his wife, Ginni, is white.)

Democrats universally decried Dobbs and urged voters to express their displeasure at the polls, which they did that fall, forestalling the predicted “red wave.” Still, Republicans won a narrow majority in the House, and there was no direct action against the Court before Democrats handed over control in January 2023.

In one exchange, Chafetz wondered aloud whether Congress should consider “cutting off the Supreme Court’s air conditioning budget.” The quip drew a faint chuckle from the crowd, but Doerfler, deadly serious, interjected: “It should not be a laugh line.”

Meanwhile, the academic debate was still brewing. In February 2022, the scholars Willy Forbath and Joseph Fishkin released a landmark book, The Anti-Oligarchy Constitution, that offered a bird’s-eye map for court reformers by updating Progressive Era arguments about constitutional law for the present day. Positively and brilliantly reviewed by the law scholar Caroline Fredrickson in that April’s Washington Monthly, the 640-page opus argued that today’s liberals ought to embrace a concept called “popular constitutionalism,” which would greatly widen the present-day conception of who gets to interpret the Constitution and what sorts of questions are “constitutional” ones.

Right now, the Supreme Court jealously guards for itself the task of deciding what the Constitution means, and it thinks of that meaning narrowly, as a question of individual rights and the limits of the federal government’s power. In contrast, popular constitutionalism says that all three branches of government, and all Americans, should see themselves as “constitutional” actors. Furthermore, it holds that many more kinds of questions about how we order society should be considered constitutional issues. The Constitution doesn’t just stop the government from interfering with private citizens; it also implies that government has the obligation to do certain things for the people—to fight against wealth concentration, for instance, and to provide economic opportunity. Forbath and Fishkin’s book offered a holistic view of the current crisis of the Court: It’s not just one policy or another that will fix it, but rather the grander project of building a society that shares broadly the responsibility of deciding these fundamental questions.

In November of that year, the Anti-Oligarchy authors discussed their book at a Georgetown Law School conference stacked with all the big names in the academic reform movement, as well as major figures like Maryland Representative Jamie Raskin and E. J. Dionne of The Washington Post. The event, which was organized by the American Constitution Society, a left-leaning counterpart to the Federalist Society founded in 2001, had an air of possibility, of action and invention, in sharp contrast to the glum “what-can-you-do” coverage that followed Dobbs. Unlike other places of public discourse, there was a willingness to directly confront the Court, and even to take action against the justices themselves.

Whether reformers ultimately embrace a confrontational strategy or a more moderate, institutionalist approach—or some combination thereof—will depend on a wider debate that should begin now. America as a whole ought to think about how its shared values can inform a new vision for the Court.

“I want to suggest that courts are the enemy, and always have been,” Josh Chafetz, a Georgetown Law professor of the “disempowering” school, said on an afternoon panel with Doerfler, Sitaraman, and another Georgetown scholar, Victoria Nourse. In one exchange, Chafetz called for retaliation against the justices as individuals, wondering aloud whether Congress should consider withdrawing funding for law clerks or even “cutting off the Supreme Court’s air conditioning budget.” The quip drew a faint chuckle from the crowd, but Doerfler, deadly serious, interjected: “It should not be a laugh line. This is a political contest, these are the tools of retaliation available, and they should be completely normalized.” What put us here, he said, is the idea that the Court is an “untouchable entity and you’re on the road to authoritarianism if you stand up against it.”

As could be expected, the institutionalists and disempowerers rehashed the major points of their debate, and they and others threw out still more ideas to reform the Court. An inventive and yet eminently practical one came from Sitaraman, who proposed a Congressional Review Act for Supreme Court decisions, similar to what already exists for executive branch regulations, that would give legislators a fast track through their own procedures in order to quickly respond to court rulings. Later, spitballing, Chafetz imagined a remedy of linguistic dimensions: Have executive agencies abandon the legalese that they use when writing policy. Instead of using Latin phrases and citing precedent in anticipation of being dragged into court, bureaucrats would be freed to express themselves in language that reflected the priorities of the people they serve.

Forty years and a few months earlier, another possibility-filled symposium drew together a band of starry-eyed eggheads to reimagine the Supreme Court. That was the founding meeting of the Federalist Society, a rapturous weekend at Yale in April 1982 during which conservatives hatched a scheme to train up ideologically complaisant lawyers and stack the judiciary with them. In November 2022, Dionne, the Post columnist, suggested that the Georgetown conference might be the beginning of a similar liberal-leaning transformation. “Maybe this gathering will be the early history of what happens next,” he said.

Those who make comparisons between today’s reform movement and the Federalist Society should keep in mind that it took the conservatives 40 years to transform the Court. Though there are changes that can and should happen now, reformers should also be thinking in longer arcs.

Right now, the conservative justices have through their own actions given momentum to one shorter-term reform: ethics. A litany of the misconduct revealed over the past year would take up too much space, but what’s notable is that it has shaken some Democrats into confronting the Court more directly. Senators Sheldon Whitehouse and Dick Durbin, of the Senate Judiciary Committee, are pressing ahead with an investigation into whether the justices’ failure to report billionaires’ gifts might have broken other federal laws. Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer has taken to attacking the present Court’s legitimacy, calling it the “MAGA Court.” Biden himself acknowledged, this past summer, that this is “not a normal court.”

Still, with 2024 looming, the Democrats are shying from more fundamental institutional conflict. This may be wise, electorally; their voters are already activated over Roe, and a more direct challenge to the conservative supermajority could ring alarm bells in the Republican base (and further antagonize the justices, who might well end up deciding the election). But there are a few changes that political leaders can and should consider now. One is for Congress to adopt its own set of enforceable ethics rules for the Court, which, at a minimum, would signal the legislative branch’s willingness to assert itself as a check on the judiciary. Another, a simple change of Senate rules, is to get rid of “blue slips,” a practice that gives home-state senators an effective veto over appointments and allows Republicans to block lower-court judges for political reasons. Other ideas to reduce the brinksmanship of judicial appointments include a proposal that the Senate should have a time limit to hold hearings and vote on nominees.

Much else depends on building electoral majorities and an energized coalition that understands the issues and presses political leaders to act. But if Democrats win back Congress and hold the White House next year—admittedly an uphill climb—they should also consider passing Sitaraman’s Congressional Review Act. Right now, Congress doesn’t have an easy path through the filibuster to clarify its legislation, which leaves the justices with the last word on what lawmakers had in mind when they wrote a federal statute. As Sitaraman once put it, Congress needs a way to say, “No, this is what we meant.”

The Supreme Court didn’t get this way all by itself. A deepening political divide has exposed structural weaknesses in American government, expressing itself in an ineffectual Congress that struggles even to pass a budget, an imperial presidency that has taken on most actual governing, and a partisan, overreaching Supreme Court. For the Court to change in a more fundamental way, the forces pressing on it will have to change as well.

In the middle to long term, that means strengthening Congress, and encouraging it to push back on the Court’s usurpations of its constitutional powers. The executive branch, too, should assert itself as a constitutional actor in dialog with the Court. In that vein, some reformers advocate for what Doerfler calls “the tool of conflict”—that is, running popular reforms into the buzz saw of the Court. The tactic might seem futile to some, but the accelerationists of the reform community argue that it can help build political momentum by focusing the public’s attention on the rights and privileges that the Court is denying them. The Biden administration did something like this with its student loan forgiveness program, which it advanced despite the widespread—and correct—expectation that the Court would strike it down.

The 2021 Presidential Commission, despite its flaws, helped to identify another fix with bipartisan potential: term limits for Supreme Court justices. The policy enjoys wide support, most state supreme courts already use it, and, as the commission pointed out, “The United States is the only major constitutional democracy in the world that has neither a retirement age nor a fixed term limit for its high court Justices.” Replacing a justice every two years would reduce the randomness of illness, the unfairness of strategic retirements like Anthony Kennedy’s, and the political stakes of judicial appointments. It would make the Court somewhat more responsive to elections and changing views, and ensure that each presidential term comes with a certain number of appointments—a persistent concern given that Republican presidents have placed far more justices on the Court in recent decades, in proportion to the number of years they have controlled the White House.

There are a surprising number of complications to this seemingly commonsense reform, though, which make it a longer-term prospect at best. The Constitution says that justices shall serve “during good behavior,” which is widely understood to mean for life. Advocates have found ways around this by proposing that term-limited justices remain on the bench but assume “senior” status, among other workarounds, but the constitutionality of the idea is still unclear. And most of all, the implementation is incredibly important. What do you do with the justices already on the bench? In a 2021 paper, Dan Epps and three coauthors, Adam Chilton, Kyle Rozema, and Maya Sen, modeled the historical life spans and retirement times of justices to estimate how long it would take to achieve a fully term-limited Court based on different implementations. If reformers rotated a justice off every two years starting today, the transition would take 18 years. If they waited for the current nine to retire, it could take half a century.

Some of the more sweeping structural reforms, like Epps and Sitaraman’s grand reordering and the aggressive disempowerment of Doerfler and Moyn, also probably belong in this long-term category. And whether reformers ultimately go with a confrontational strategy or a more moderate, institutionalist approach—or some combination thereof—will depend on a wider public debate that should begin now. The liberal base, and America as a whole, ought to think about how its shared values can inform a new vision of what the Court is for.

On March 9, 1937, Franklin Roosevelt devoted one of his fireside talks to an explanation of his plan to pack the Supreme Court. His complaints about the justices sound like they could have been uttered this very day: The Court had “improperly set itself up as a third House of the Congress—a superlegislature … reading into the Constitution words and implications which are not there and which were never intended to be there.”

And in a rhetorical frame that today’s reformers should copy, Roosevelt made clear that the fight was not between the president and the Court, but the Court and the people. In a parable of sorts, he likened the American government to a plow being pulled by a three-horse team. One horse, the judiciary, had gone off in its own direction, threatening to break the whole contraption apart. He, FDR, was trying to bring the team back together. But that didn’t mean he was taking control of the entire plow cart of state. The president, after all, is just another horse. (And as we all know, horses follow public opinion.)

“It is the American people themselves,” Roosevelt said, “who are in the driver’s seat.”