In 1976, ABC named Barbara Walters co-anchor of the network’s nightly news, with an unprecedented salary of $1 million. In the golden era of television news, Walters was the first woman to hold the high-profile anchor seat on a major network. Predictably, the announcement set off a cascade of tremors through the industry. The press mocked Walters’s appointment with headlines like “Doll Barbie to Learn Her ABCs” and “Barbara Walters: Million-Dollar Baby?”

Walters was no baby doll. She was a twice-divorced, 47-year-old single mother who had spent a quarter century building a broadcasting career, including a dozen years at NBC’s top-rated Today show, ultimately serving as its first female cohost. Walters’s charisma and incisive interviews helped increase Today’s viewership and NBC’s profits. Earlier that year, Gallup listed Walters among the 10 most admired women in America. Still, at a time when even the veteran CBS anchorman Walter Cronkite—dubbed “the most trusted man in America”—earned only $400,000 a year, Walters’s million-dollar salary was eye-popping. And controversial.

Certainly, the media critique and Walters’s icy reception from male colleagues reflected the casual sexism of the era. But the scorn did not merely reflect doubts about a woman claiming the anchor chair, a vaunted position of public trust. Even in 1976, years before she perfected the hourlong, one-on-one TV interview, before the eponymous news specials and much-criticized intimacy with celebrities, Barbara Walters posed a threat to traditional journalism, thanks to her deliberate blurring of the lines between news and entertainment. Cronkite himself greeted the announcement of Walters’s promotion with a “wave of nausea, the sickening sensation that perhaps we were all going under, that all of our efforts to hold network television news aloof from show business had failed.” The Washington Post opined, “The line between the news business and show business has been erased forever.”

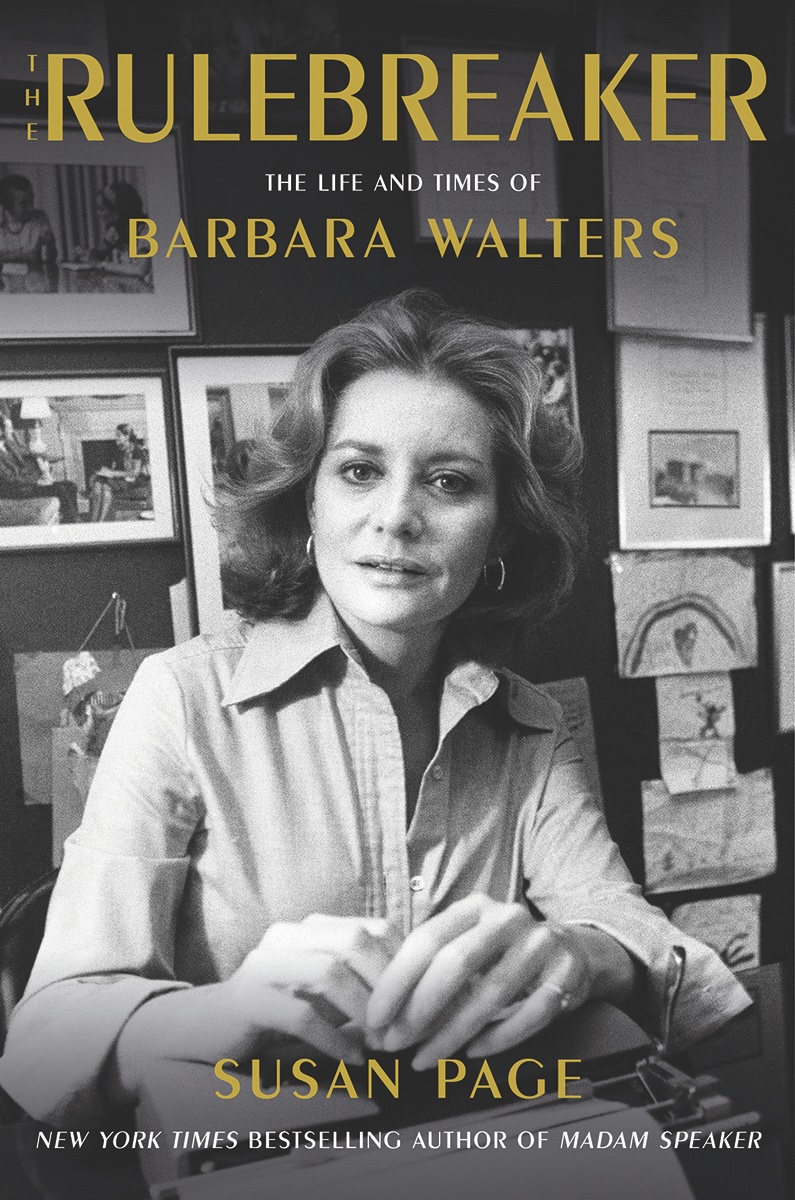

Rulebreaker, Susan Page’s excellent new biography of Barbara Walters, is a nuanced, deeply researched history of the legendary newswoman, who died in 2022 at the age of 93. The book ticks all the boxes for a compulsively readable celebrity biography, relating Walters’s improbable rise to fame, her tumultuous personal life, and plenty of juicy gossip featuring a veritable who’s who of the past 70 years. But Page, the author of best-selling biographies of former House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and First Lady Barbara Bush, rightly keeps the focus on Walters’s propulsive career, her groundbreaking role as a woman in news media, and her controversial legacy in transforming television journalism.

Nothing in Barbara Walters’s adolescence or early adulthood foreshadowed her future success. An average student at Sarah Lawrence College, she demonstrated no particular interest in current events or journalism. For a decade, she held a series of entry-level jobs in public relations and local television. But after her brief first marriage ended and her father’s fortune evaporated, Walters found herself a divorced woman with no safety net in need of a well-paying career. In 1961, Walters was hired as “the girl writer” on NBC’s Today show, but soon began strategizing to join the broadcast. At the time, there were only token opportunities available for a woman, typically reserved for a former actress or beauty queen. Though Walters later modestly claimed that “it never occurred to me that I would ever have a regular on-air role myself,” her colleagues recalled otherwise. A former production assistant remembered, “Barbara was nagging to be on the air … She was just badgering everyone half to death.” Walters distinguished herself through a willingness to take on all tasks, from hawking a sponsor’s dog food to narrating fashion shows. She became a reporter, first in the field, then on set, eventually rising to cohost.

Walters is a complicated icon for feminists, and a reminder that a pioneer is not necessarily an instigator for change. Her own comments about women in media sometimes echoed sexist tropes.

The Rulebreaker teems with examples of sexism in the workplace. For years on Today, Walters was relegated to the “girlie” stories—puff pieces—rather than hard news. Today’s host, Frank McGee, prohibited her from speaking to guests until he had asked three uninterrupted questions. Walters circumvented the rules by booking her own interviews with news makers offsite.

But Walters is a complicated icon for feminists, and a reminder that a pioneer is not necessarily an instigator for change. Her own comments about women in media sometimes echoed sexist tropes. For example, she told a reporter, “I think that a little of a woman goes a long way on television … For one thing, our voices are different and can easily become tiresome.” In the 1970s, as the women’s movement became pervasive, Walters held herself apart. When her female colleagues at NBC spoke out against discrimination in the workplace, she did not join them. “Barbara was determined to win the game, not change its rules,” Page concludes. “The path she ended up clearing for the women who followed her was, first and foremost, one that she was cutting for herself.”

At Today, Walters eventually earned the right to cover hard news. In a four-hour interview with Secretary of State Dean Rusk that “helped give her an imprimatur as a serious journalist,” Page writes, Walters pushed Rusk to discuss the public’s critique of the Vietnam War, and his response made headlines and the evening news. But she became best known for her exhilarating interviews with entertainers, and her interviewing portfolio grew to include everyone from Prince Philip to Judy Garland. Her father had been a nightclub impresario, and Barbara spent her adolescence rubbing shoulders with celebrities, alongside gamblers and mobsters. This early exposure gave her an ease among the famous and powerful.

In network television, the seamless transition from “women’s stories” to hard news was part of the morning show’s appeal. Not so for the evening news. When Walters was named the co-anchor of ABC News, the network’s flagship evening newscast, her critics cast her as solely responsible for threatening the separation of news and entertainment. But the truth is more complicated. As Page illustrates, even before Walters’s arrival, William Sheehan, the president of ABC News, had called for more news stories “dealing with the pop people. The fashionable people. The new fads. Bright ideas. Changing mores and moralities.” Or, as Page notes, “the sort of lifestyle topics that had always been in Barbara’s wheelhouse.” Tellingly, her initial ABC contract was shared between the entertainment and news divisions, a legal acknowledgement of her blended role.

Walters transformed the content of the newscast. For her debut, ABC led with hard news—Walters’s taped interview with Egyptian President Anwar Sadat—followed by her interview with Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir the next day. But Walters also addressed viewers directly, saying, “I’d like to pause from time to time as we show news items to you and say, ‘Wait a minute. What does this mean to my life and yours?’ ” Today, bringing attention to the everyday impact of seemingly distant events is commonplace in broadcast news, Page notes, but in 1976, it was revolutionary.

But Walters struggled in her new job—the stiff, sober reading of news reports written by others did not play to her strengths, and on-air tensions with her co-anchor, Harry Reasoner, a self-proclaimed male chauvinist, were so palpable that the news director instructed the cameraman to avoid angles that captured both anchors in a single shot. She lasted just two years in the role, but the changes she introduced to the show remained.

Once released from the constraints of a nightly news broadcast, Walters moved to ABC’s newsmagazine show 20/20 and focused on her specialty, the long-form interview. Blockbuster prime-time interviews, including her annual Oscar night series and her “10 Most Fascinating People” franchise, became Walters’s signature events. She was a ruthless competitor and indefatigable in her pursuit of a subject, throwing pebbles at Sadat’s window at 11 p.m. to capture his attention after a security guard refused to deliver a message. At Camp David, she was once discovered hiding in the women’s bathroom, hoping to grab an exclusive, after the rest of the press pool had boarded the bus home.

To achieve success, she used all the tools in her toolbox. She wore short skirts, flaunting her “good legs,” and flirted with her subjects, including Cuban President Fidel Castro, with whom she was rumored to have had an affair. In a comment that would make feminists wince, she wrote in her 2008 memoir, “Sex rears its happy little head, and a sought-after male subject chooses you to do the interview in the hope that somewhere along the line, the romantic side—or at least the flirtatious side—will surpass the professional.” At the first-ever shared interview with Sadat and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin, Begin began the interview by cooing, “Mr. President, don’t you think she’s the prettiest reporter you’ve ever seen?”

In an era when news organizations made room for—at most—a single token woman, Walters jealously guarded her turf from female colleagues. Her rivalry with Diane Sawyer, a co-anchor at ABC, was legendary. “Diane will stab you in the back,” an ABC veteran recalled, “[but] Barbara will stab you in the front.” Walters resented the women who followed her, who “had it easy,” Page writes. In one telling anecdote, Walters was surprised to see that ABC had provided a room for the Good Morning America co-host Joan Lunden’s toddlers, noting that no one had done that for her when she was a new mother. Walters had built her own career without the benefit of female role models or mentors, and only relatively late in her career did she relish that role for herself, nurturing young women on her staff and emerging journalists.

Page dissects Walters’s mastery of the television interview, describing how she often built to a climax with a final short, direct question crafted to grab headlines. Walters “raised the art of the ‘get’ to a contact sport,” Page writes. Landing interviews with Castro, Vladimir Putin, and Palestine Liberation Organization leader Yasser Arafat, Walters earned the grudging respect of traditional journalists. In 2011, at age 82, she snagged a coveted sit-down with Syrian President Bashar al-Assad. She posed tough questions and held him to account for wartime atrocities. David Kenner of Foreign Policy wrote, “Everyone who made snarky questions about Walters’ lack of qualifications to conduct this interview should be eating crow (and that includes me).” During the course of her career, Walters interviewed every sitting president and first lady from Richard Nixon through Barack Obama, and moderated two presidential debates.

And yet, she earned her reputation for asking softball questions, cozying up to celebrities, and making her subjects cry. (Vanity Fair wrote, “Almost single-handedly, Barbara Walters turned TV interviewing into the weepily empathetic kudzu that has swamped broadcast journalism.”) More traditional journalists dismissed her subjects—convicted murderers, crime victims, movie stars, athletes—as too lowbrow, but Walters “saw it as a brag,” Page writes. She had an uncanny ability to tap into the public’s curiosity, serving up the questions everyone wanted answered—asking the singer Ricky Martin if he was gay, Putin whether he had ever ordered anyone killed, and Nixon whether he regretted not burning the White House tapes.

In 1997, Walters launched The View, “a floating focus group” featuring women of different backgrounds and generations that fluidly combined entertainment news and political commentary. The New York Times later dubbed it “the most important political TV show in America.” Her primetime specials were ratings juggernauts—her 1999 interview with Monica Lewinsky attracted 70 million viewers, at the time a record for any news program.

As Walters cemented her superstardom in the 1990s, the industry was changing. News programming scarcely resembled the days when Cronkite, Chet Huntley, and David Brinkley held 40 million viewers’ daily attention for 15 minutes of carefully scripted, soberly recited hard news. The networks had traditionally run their news divisions at a loss and made their revenue from entertainment programming, but news was becoming an import profit center, sometimes compromising the quality of journalism. Questionably newsworthy true crime programs like Inside Edition and Hard Copy proliferated.

How much of this change—the transformation of television journalism, the elevation of sensational content, the pandering to prurient interests—can we pin on Walters? Page is reluctant to pass judgment. As the Washington bureau chief of USA Today, a newspaper partly responsible for the death of local newspapers and the quintessential example of dumbing down the news, she is not exactly a disinterested observer. Page concludes The Rulebreaker with a recitation of the myriad ways Walters was a pioneer for women in journalism, and adds her to a short list of luminaries who have shaped television news, including Edward R. Murrow, Mike Wallace, Cronkite, and Roger Ailes. Other observers haven’t been so kind. The media critic Eric Boehlert once wrote that Walters “pioneered the transformation of television news into, literally, parlor gossip.”

She had an uncanny ability to tap into the public’s curiosity, serving up the questions everyone wanted answered—asking Nixon, for example, whether he regretted not burning the White House tapes.

In 2014, on what was to be Walters’s final episode of The View, a parade of more than two dozen of the nation’s most famous women in broadcasting assembled to honor her storied career. Surrounded by Jane Pauley, Katie Couric, Diane Sawyer, Lunden, and other luminaries, Oprah Winfrey spoke for them all, saying, “I want to thank you for being a pioneer, and everything that that word means. It means being the first, the first in the room, to knock down the door, to break down the barriers, to pave the road that we all walk on.”

Walters basked in the praise, momentarily speechless, and pointed to the accomplished women surrounding her. “These are my legacy,” she said. Indeed, it’s a legacy worth celebrating. But in an industry refashioned in her image, it’s far from her only one.