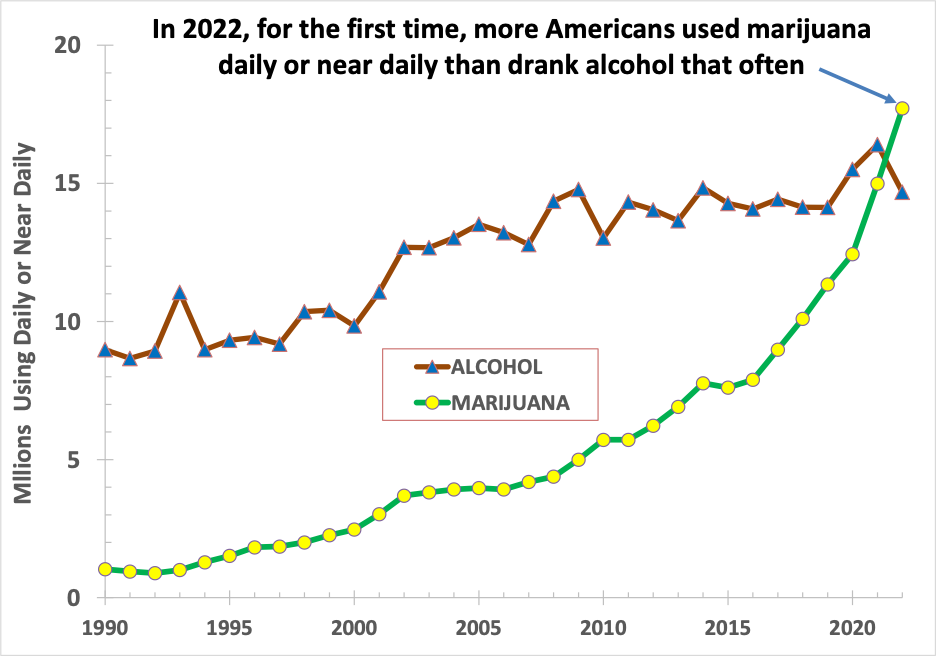

A new study has documented a remarkable rise in Americans’ use of marijuana. Over the last 30 years, the number of people who report using the drug in the past month has risen fivefold from 8 million to 42 million. Through the mid-1990s, only about one-in-six or one-in-eight of those users consumed the drug daily or near daily, similar to alcohol’s roughly one-in-ten. Now, more than 40 percent of marijuana users consume daily or near daily. The increased use is important to recognize as President Joe Biden plans to reschedule marijuana from a Class I to a Class III drug.

At the nadir of modern marijuana use, in 1992, just 0.9 million Americans reported using marijuana daily or near daily. That number had grown twenty-fold to 17.7 million by the most recent survey in 2022. For the first time, more Americans report using marijuana daily or near daily than they do drinking that often (17.7 million vs. 14.7 million).

Legalization and commercialization have produced a spectacular rise in the potency of cannabis products. Until the end of the 20th century, the average potency of seized cannabis never exceeded 5 percent THC, its active intoxicant. Now, the labeled potency of “flower” sold in state-licensed stores averages 20-25 percent THC. Extract-based products like vape oils and dabs routinely exceed 60 percent. Back in the 1990s, a person averaging two 0.5-gram joints of 4 percent THC weed per week was consuming about 5 milligrams of THC per day on average. Today’s daily users average more than 1.5 grams of material that is 20-25 percent THC, which is more than 300 milligrams per day. That is far more THC than is consumed in typical medical studies of its health effects.

This spike in marijuana usage and THC consumption might seem unimportant in an era when fentanyl and other synthetic drugs are killing over 80,000 Americans per year, but describing a drug as less dangerous than fentanyl is damning with faint praise. There are exceptions, of course, but on the whole, daily marijuana use is neither health-promoting nor performance-enhancing for the typical daily user.

On the positive side, the kids are mostly all right. Just 2 percent of 12-17 year-old marijuana users consume daily or near daily. As a result, youth account for just 3 percent of the 8.3 billion annual days of self-reported marijuana use in the country. Adult (18+) daily and near-daily users account for three-quarters of those days of use—and a considerably greater share of consumption because they use more per day than weekend-only users.

Indeed, marijuana is becoming something of an old person’s drug. As a group, 35-49-year-olds consume more than 26-34-year-olds, who account for a larger share of the market than 18-25-year-olds. The 50-and-over demographic accounts for slightly more days of use than those 25 and younger.

Still, it is worth asking what the population effects are of so many people consuming high-strength cannabis regularly. Science has struggled to keep up with the new world of cannabis, but potentially concerning signs include increases in emergency room visits for both psychotic episodes and cannabis-induced cyclical vomiting, increased risk of cardiovascular disease, and higher rates of automotive crashes involving impaired drivers. And gram for gram, smoking cannabis creates about as many carcinogens, tars, and other lung-damaging chemicals as tobacco—although grams consumed per day is only about one-tenth as great. For others, the effects might be the opposite of a cognitive enhancer, with intoxication adversely affecting short-term memory, concentration, and motivation, resulting in lost opportunities in schools and the workplace.

The biggest long-term medical health risk may concern serious and lifelong psychiatric conditions such as schizophrenia. Early hopes—not to say hype—that cannabis would prove an effective medication for mental health disorders have been challenged as studies repeatedly find that use concurrent with conditions like depression and PTSD often predicts a worse course of illness.

Regulators need to take seriously their responsibility to protect the public from cannabis companies. At the dawn of legalization, many envisioned the cannabis industry as a hippy-led anti-materialist cottage industry, and supply by non-profits is an option, but today’s industry is dominated by the same sorts who run the tobacco industry (indeed, one of the largest investors in the industry in Canada is the tobacco industry). Limits on potency and product form are nearly absent in the U.S., as are constraints on advertising and running illegal pot shops.

Federal leadership is needed, and the Biden Administration’s proposal to shift marijuana to Schedule III is a good start, but Schedule III drugs can only be dispensed by pharmacies in response to a doctor’s prescription. Some who consume for non-medical reasons may also need a nudge toward temperance to avoid problems from heavy consumption.

But this is also a matter of culture and social norms, not just legal controls. Parents need to shake off their historical understandings of the drug as well as their fears of being pilloried as a 1980s-style anti-pot crusader and educate themselves about this new era of cannabis. Teachers, pediatricians, and other professionals entrusted with caring for young people must also up their game. And it isn’t just about the kids. Thirty-something-year-olds who see a friend’s use getting the better of them need to speak up, too.

Cannabis isn’t fentanyl, but it isn’t lettuce, either. The vastly increased use of the drug is not all benign, and we may come to regret it if we fail to recognize and respond to these trends.