Student protestors at college campuses nationwide, united by their outrage at Israel’s actions in Gaza, can rightly be described as diverse. Despite the masks, it’s clear that they come from different racial backgrounds, and their views range from the belief that Israel should give up on its war effort to the conviction that Israel should be destroyed entirely.

But one thing is not especially diverse about the protests: the campuses on which they’ve been happening.

Many of the most high-profile protests have occurred at highly selective colleges, like Columbia University. But since the national media is famously obsessed with these schools and gives far less attention to the thousands of other colleges where most Americans get their postsecondary educations, it’s hard to know how widespread the campus unrest has really been.

We at the Washington Monthly tried to get to the bottom of this question: Have pro-Palestinian protests taken place disproportionately at elite colleges, where few students come from lower-income families?

The answer is a resounding yes.

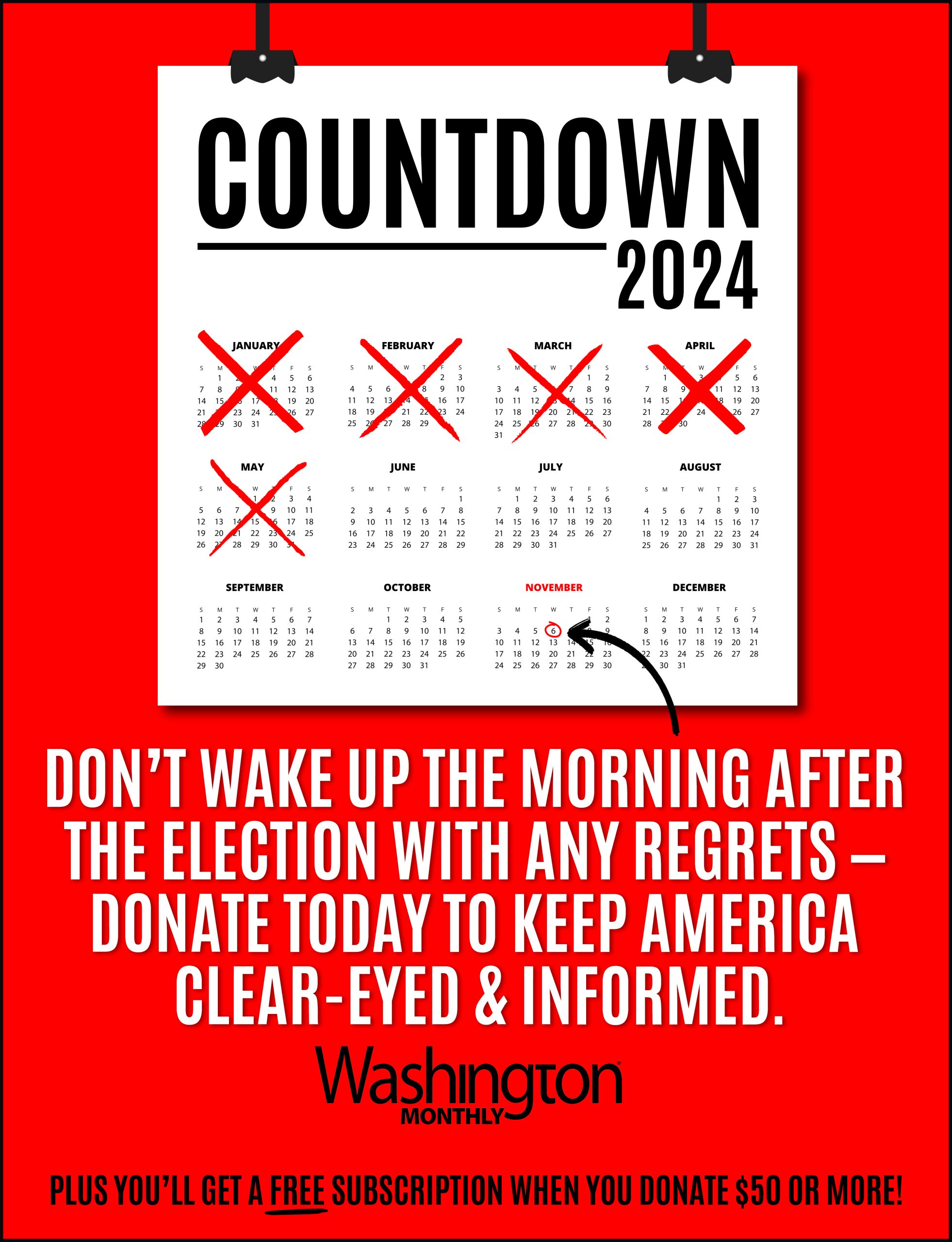

Using data from Harvard’s Crowd Counting Consortium and news reports of encampments, we matched information on every institution of higher education that has had pro-Palestinian protest activity (starting when the war broke out in October until early May) to the colleges in our 2023 college rankings. Of the 1,421 public and private nonprofit colleges that we ranked, 318 have had protests and 123 have had encampments.

By matching that data to percentages of students at each campus who receive Pell Grants (which are awarded to students from moderate- and low-income families), we came to an unsurprising conclusion: Pro-Palestinian protests have been rare at colleges with high percentages of Pell students. Encampments at such colleges have been rarer still. A few outliers exist, such as Cal State Los Angeles, the City College of New York, and Rutgers University–Newark. But in the vast majority of cases, campuses that educate students mostly from working-class backgrounds have not had any protest activity. For example, at the 78 historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs) on the Monthly’s list, 64 percent of the students, on average, receive Pell Grants. Yet according to our data, none of those institutions have had encampments and only nine have had protests, a significantly lower rate than non-HBCU schools.

Protest activity has been common, however, at elite schools with both low acceptance rates and few Pell students. You can see these findings in the chart below.

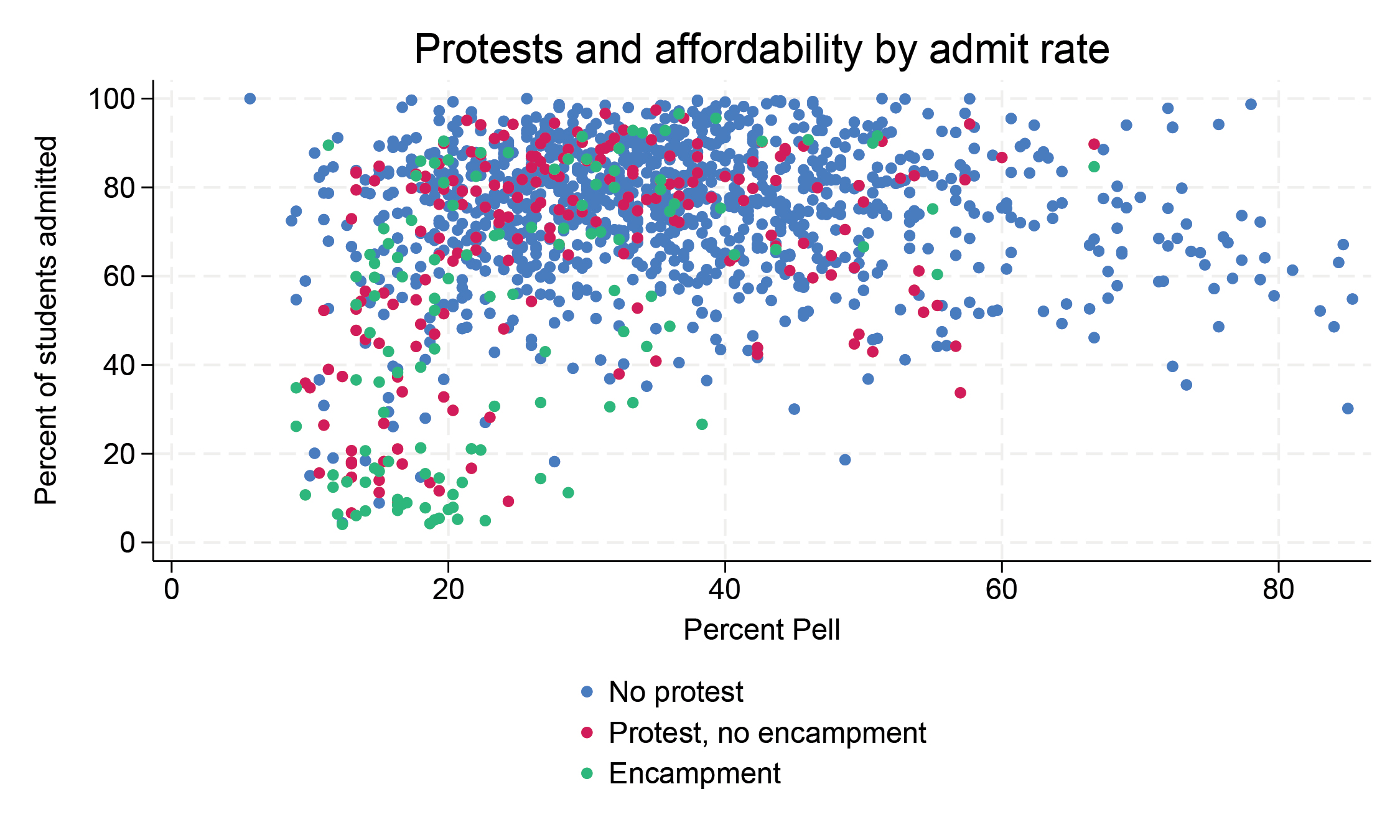

When you separate out private and public colleges, the difference becomes even more stark, as the next chart demonstrates. At private colleges, protests have been rare, encampments have been rarer, and both have taken place almost exclusively at schools where poorer students are scarce and the listed tuition and fees are exorbitantly high.

Out of the hundreds of private colleges where more than 25 percent of the students receive Pell Grants, only five colleges have had encampments.

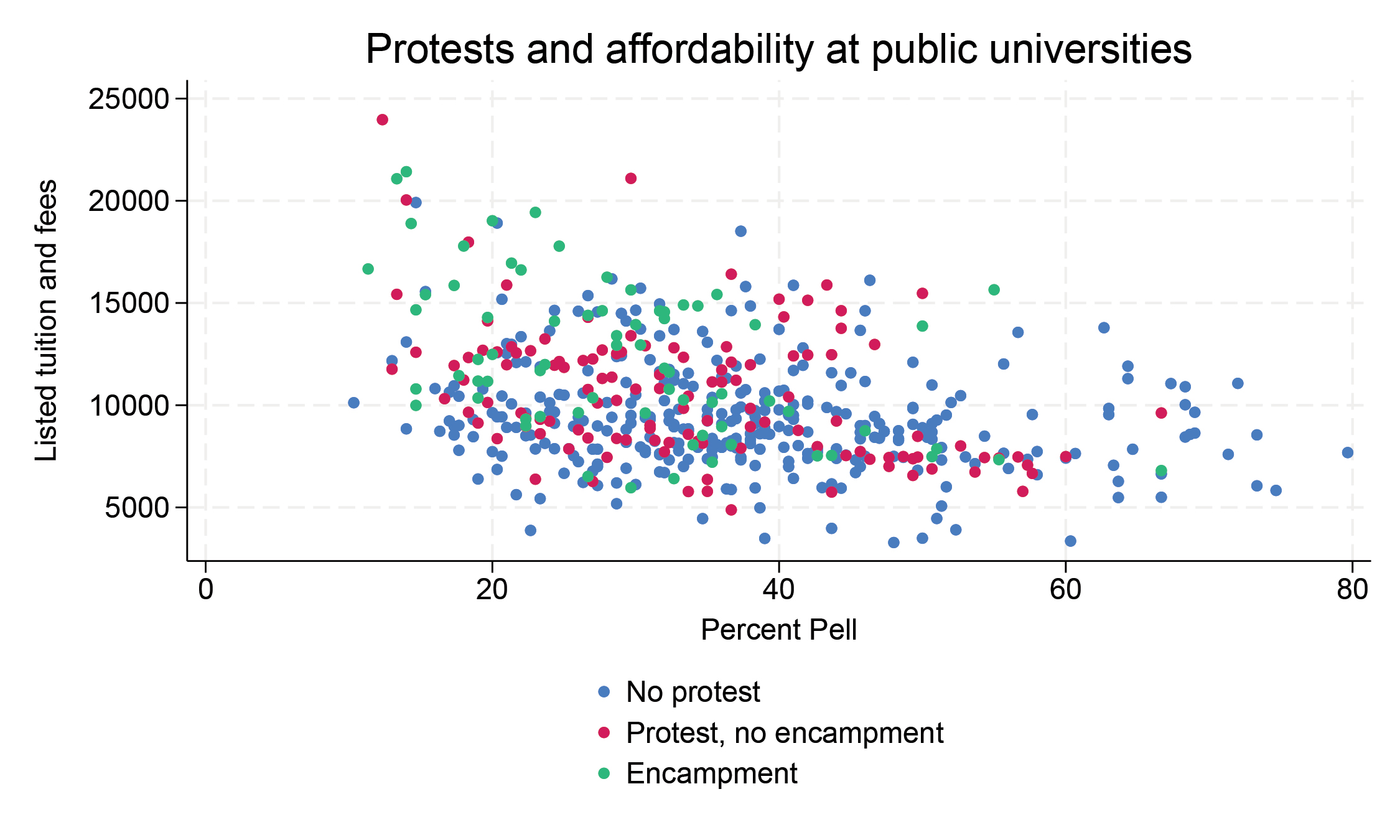

Protests and encampments have been more common at public colleges. This is in part because these colleges just have more students, and only a few students are needed for a protest. Even at public colleges, though, there is a clear relationship between having fewer Pell students and having had a protest or encampment, as the chart below illustrates.

Why is it that protests are so concentrated at more elite colleges and rare at those with larger percentages of working-class students? One possible explanation is that the more selective and wealthier colleges attract and encourage students who are more public minded and socially active.

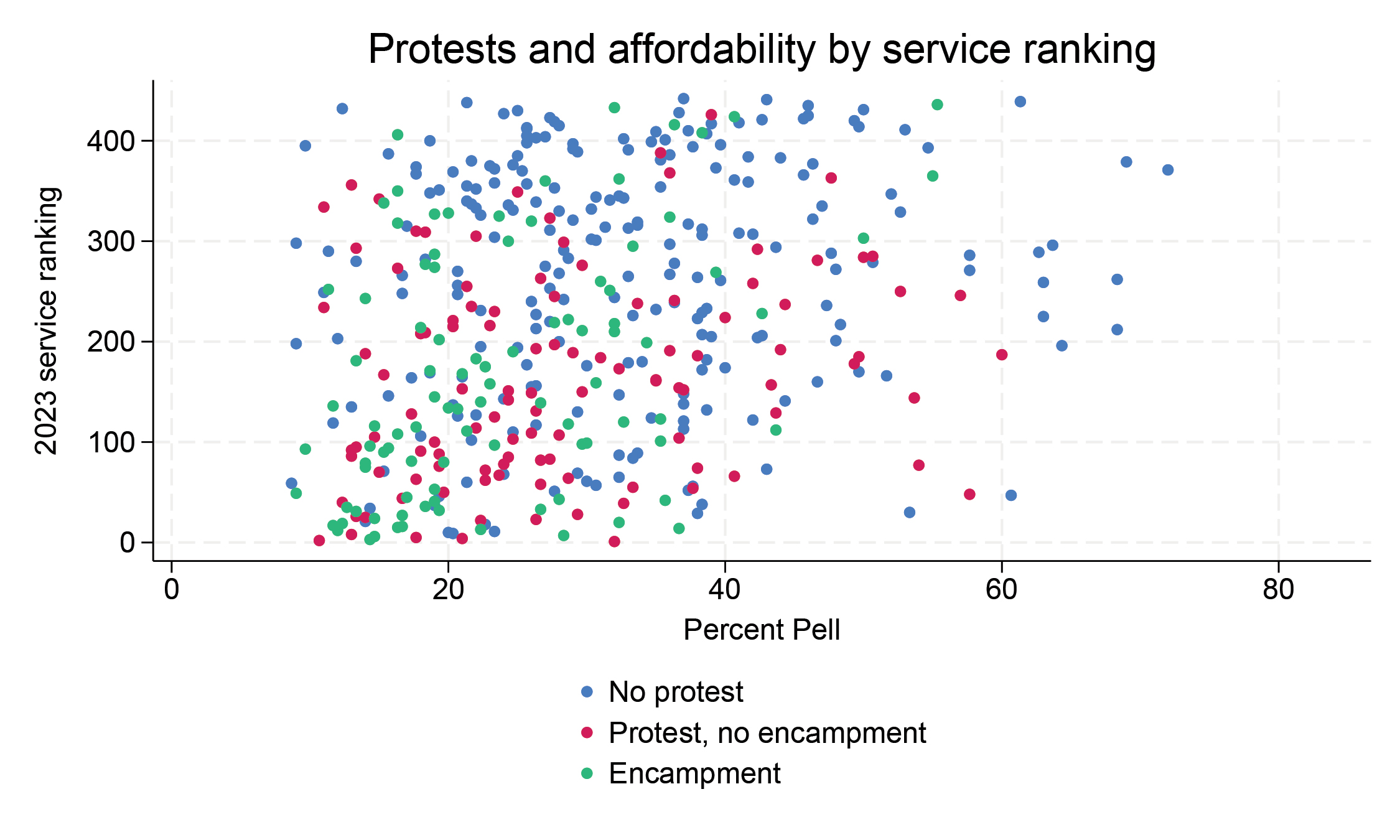

To test that hypothesis, we compared the list of schools that have had protests and encampments to our 2023 rankings of national universities, where the lion’s share of protest activity has happened, based on a set of “service” metrics we use to gauge democratic engagement. These include the number of students at a college who serve—before, during, or after attending the school—in AmeriCorps, the Peace Corps, ROTC, and local community nonprofits through work study; the percentage of students registered to vote and the degree to which the school makes student voting easier; and whether a school is listed on the Carnegie Community Engagement Classification, which recognizes colleges that document their broader public engagement efforts.

As you can see in the chart below, schools that have high scores on the Washington Monthly service rankings (the bottom of the Y axis) are a bit more likely to also have had protests and encampments. But in general, the distribution looks more random, especially compared with the previous three charts. In other words, having high levels of student democratic engagement—at least according to the Monthly’s metrics, which are the most extensive we know of—is far less correlated with protests and encampments than admitting low percentages of poor and working-class students.

What, then, does explain why colleges with large numbers of students of modest means are far less likely to have had protests and encampments? Our best guess is that poorer students are just focused on other concerns. They may have off-campus jobs and nearby family members to see and take care of. They might sympathize with the protesters—a nationwide poll of college students in May found that 45 percent support the encampments, 24 percent oppose them, and 30 percent are neutral. But in the same poll, only 13 percent rated conflict in the Middle East as the issue most important to them. That was well behind health care reform (40 percent), educational funding and access (38 percent), and economic fairness and opportunity (37 percent). Students burdened with multiple responsibilities—like having to work a low-paying job to pay for college to get a better-paying job—are unlikely to devote what little free time they have to protesting about an issue they don’t see as a high priority.

There could be other reasons. Some colleges have more of a history and culture of campus protesting, and while colleges are generally left-leaning, some are more so than others. At Columbia, for example, there are 5.6 liberal students for every one conservative student, whereas at the University of Texas at El Paso (where there have been no pro-Palestinian protests or encampments, and 58 percent of students receive Pell Grants), there are only 2.3 liberal students for every conservative student. Many public universities, especially in red states, are also under political pressure to keep a lid on campus protests. Students there and at other institutions, such as evangelical colleges, may fear retaliation for expressing their views on the war.

Whatever the cause, the pattern is clear: Pro-Palestinian protests are overwhelmingly an elite college phenomenon.