Why are you reading this when you could be doing jumping jacks?

And how come you’ve gone on to read this sentence when you could be having a colonoscopy?

You and I could be doing all sorts of things right now that we have reason to believe would improve our health and life expectancy. We could be working out at the gym, or waiting in a doctor’s office to have our bodies scanned and probed for tumors and polyps. We could be using this time to eat a steaming plate of broccoli, or attending a support group to help us overcome some unhealthy habit.

Yet you are not doing those things right now, and the chances are very strong that I am not either. Why not?

Even people who take their health very seriously calculate costs and benefits. Time spent at the gym, for example, is time we cannot spend playing with our kids, or making the money we need to pay for our ever-rising health insurance premiums. Submitting to a colonoscopy, while minimally costing time, money, and discomfort, may not provide us with any personal benefit whatsoever—all of which we put into the mix before deciding if this is the day we have the test done.

In short, in our day-to-day lives we regularly apply a kind of informal cost-benefit analysis to the decisions we make about health care. To take another example, say you decide it’s worth the effort to lose twenty pounds and firmly resolve to do so. Then your mind will instantly turn to mulling what would be the most cost-effective way to go about it: eat less or exercise more, for example, or perhaps take a pill or undergo a liposuction operation or some combination of all of those.

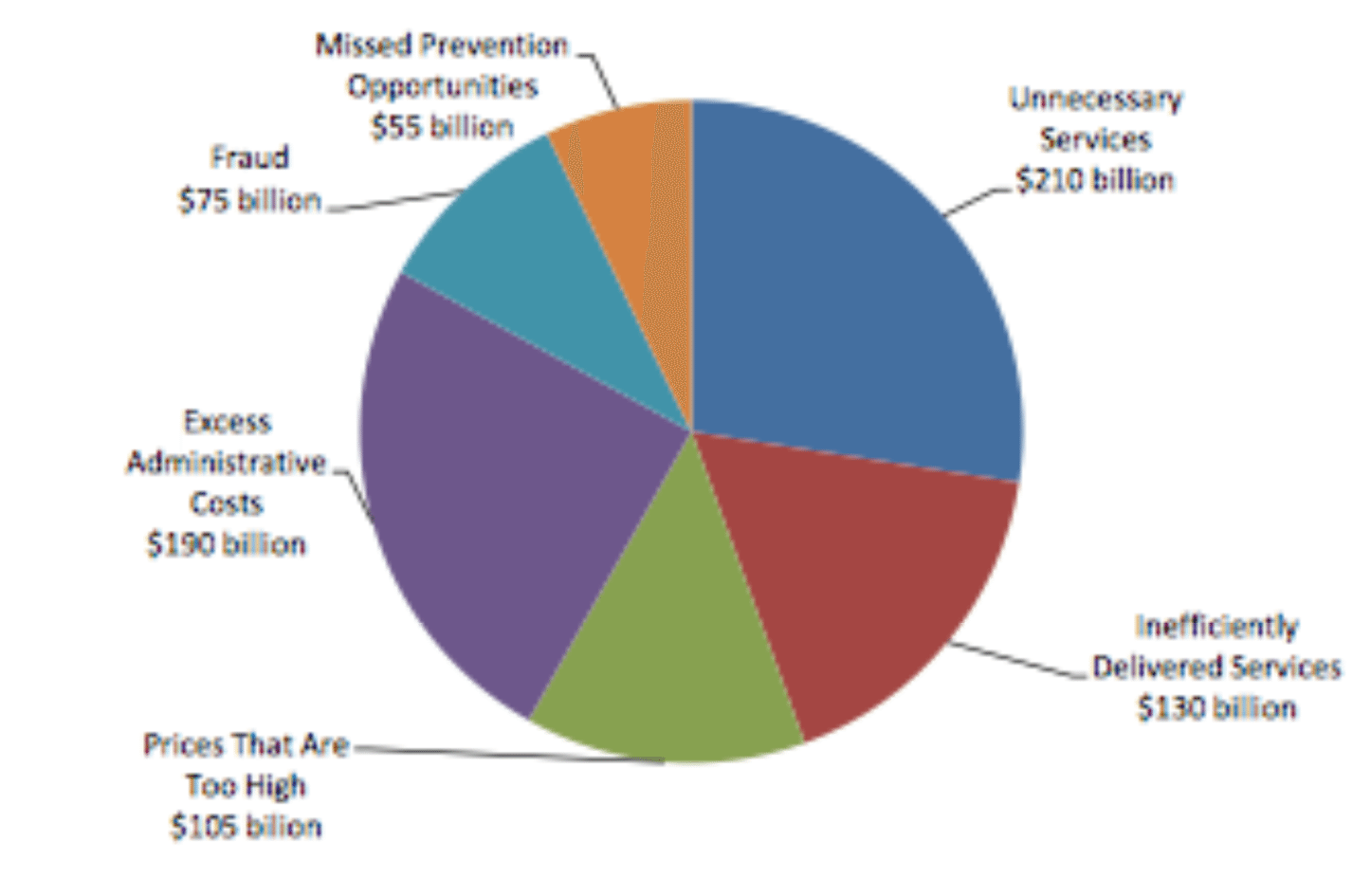

Where’s the Waste in Health Care?

Source: Institute of Medicine

In making this decision, you may well act on assumptions that are shortsighted or misinformed. You may ascribe more effectiveness to those interventions that seem easy (taking a diet pill) than to those that seem hard (giving up sweets and sweating it out in the gym more often).

Similarly, you may underestimate the risk that a liposuction will bring with it a hospital infection and other complications that will get you killed. Your decision may also be constrained by lack of money to throw at the problem, or lack of time, or competing ambitions. Yet however imperfectly, your mental energies will be directed at how to achieve your goal of losing those twenty pounds at the least cost in other things that matter to you.

This pattern of “rationing,” if you will, our own health and health care on the basis of perceived costs and benefits is arguably a defining feature of what makes us human. Certainly my fat cat does not deliberate the pros and cons of how and whether to overcome her obesity.

Yet here is a curious fact about humans, in the United States, at least. Though we spend more per person on health care than any other people on earth, and with results that are no better and often worse than all other advanced nations, we have allowed conservatives and corporate interests to bind us with laws that explicitly forbid the use of formal cost-benefit analysis to determine how health care dollars are spent. Until we get our heads around this contradiction, we are in big trouble.

The stunning inefficiency of the U.S. health care system as a whole is now beyond dispute. To see the magnitude of aggregate waste, one only has to look at the gross disparities in how medicine is practiced in different parts of the country and with what results.

The best-known work in this area comes from the Dartmouth Atlas Project. For more than a decade, researchers there have systematically reviewed the medical records of deceased Medicare patients nationwide, including those who suffered from specific chronic conditions during their last two years of life. And by doing so, the researchers have uncovered striking anomalies that point to vast inefficiencies.

In Miami, for example, the Dartmouth researchers have discovered that the average number of doctor visits for a Medicare patient during the last two years of his or her life is 106. But in Minneapolis, among Medicare patients suffering from the same chronic conditions, the average number of doctor visits during the last two years of life is only twenty-six. Yet in both cities, all of these patients are equally dead at the end of two years.

The implication is unavoidable. The much higher volume and intensity of medicine as it is practiced in Miami as compared to Minneapolis may benefit some patients in some ways. But all the extra exams, as well as the extra tests, drugs, and operations that doctors in Miami regularly order for their patients, bring no aggregate gain in life expectancy.

By extrapolating from such disparities in medical practice around the country, Dartmouth researchers have developed the widely accepted estimate that roughly a third of all health care spending in the United States is pure waste or worse, mostly in the form of unnecessary and often harmful care—amounting to some $700 billion a year. Using a similar approach of comparing best and worst practices, a recent study by the Institute of Medicine concludes that overtreatment and other forms of waste in the system consume $750 billion annually. That’s roughly the cost of the entire Iraq War.

This finding is in line with that of another recent study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (the house organ of America’s doctor lobby!). It calculates that on its current course the U.S. will spend nearly $11 trillion between 2011 and 2019 on health care that has no benefit to patients and that is often harmful to their health. Cutting that waste by just 4 percent a year, the study concludes, would be enough to keep health care spending in line with the growth of the economy, which in turn would be enough to evaporate the federal government’s long-term deficits. And it would mean that wasteful health care would no longer crowd out care that actually improves and prolongs the lives of patients.

Yet while we know the system as a whole is grossly inefficient, it remains easy for those responsible for the waste to escape detection, let alone accountability. The biggest single reason is that, due to the insistence of conservatives allied with drug manufacturers and medical device makers, the federal government is not allowed to consider the cost-effectiveness of different treatments in deciding how to invest health care dollars.

To be sure, in recent years, the Obama administration has begun to underwrite research into the so-called “comparative effectiveness” of different drugs and treatments. It has done this primarily through a new entity called the Patient-Centered Outcome Research Institute (PCORI), which was created by the Affordable Care Act. Late last year, PCORI announced its first grants and is now funding research on, for example, how well stroke victims do when they receive rehabilitative therapy at home as compared to care in nursing homes.

That’s important to know and long overdue. Most ordinary Americans would be shocked to learn how little research has been done on the outcomes of different practices in medicine, including on the actual health effects of such common, costly, and invasive procedures as back and heart surgery. For example, from 2000 through 2005, American cardiologists performed more than seven million coronary artery angioplasties, arthrectomies, and stent insertions. Yet only in recent years has there been any research to determine whether these procedures work any better than simple noninvasive treatments, such as aspirin or cholesterol pills, for patients with stable coronary disease. It turns out that they don’t.

Yet while the work of PCORI is important, it will never tell us what we most need to know to get the waste out of the U.S. health care system. That’s because, as PCORI’s executive director told a health care conference in 2011, “You can take it to the bank that PCORI will never do a cost-effectiveness analysis.”

PCORI’s work compares benefits to benefits, but not, as a matter of law, cost to benefits, and that’s a big deal. Such research does not tell us, for example, whether measures to prevent a stroke would be more cost-effective than measures to deal with its consequences. The same is true of all other government research into “comparative effectiveness.”

And by ignoring costs, such research also cannot tell us how to make sure that the money we spend on health care saves the most lives or reduces the most suffering. More fundamentally, even if the work of PCORI and other comparative effectiveness research could answer those questions, the government could not act on the information. That’s thanks to obscure but deeply consequential language inserted into the Affordable Care Act by the very corporate interests that stand to lose the most from our actually knowing which drugs and procedures offer the highest value.

The story of how this happened and what it means is full of perverse ironies. Leading up to the Obama years, mainstream health care policy experts and many politicians in both parties generally agreed on the need for the federal government to fund cost-effectiveness studies. As far back as 1996, a panel convened by the U.S. Public Health Service called for evaluating specific drugs and treatments based on how many years of healthy life they produced per dollar. When President George W. Bush signed the Medicare Modernization Act into law, he authorized $50 million to study the clinical effectiveness and appropriateness of health care services, including prescription drugs, while Bush’s Medicare program administrator, Mark McClellan, pushed for using such research in Medicare coverage decisions.

Conservatives have long championed the use of cost-benefit analysis in other realms, including those that involved putting a dollar value on both the length and quality of human life. In 1981, for example, President Ronald Reagan issued Executive Order 122911, which established the still-routine practice of evaluating consumer safety and environmental regulations based on the estimated number of lives saved per dollar. In 2003, under the Bush administration, the Environmental Protection Agency even went so far as to adopt the so-called “life expectancy” factor in cost-benefit analysis, which recognizes that more years of life are saved when children are spared death than when elders are. At the time, it wasn’t conservatives who objected, but some environmentalists and senior groups, who characterized the policy as imposing a “senior death discount.”

As late as 2008, Republican presidential nominee John McCain issued a position paper, entitled “Straight Talk on Health System Reform,” that reflected the bipartisan consensus on the need for government research into the actual value of different drugs and treatments. Based on the thinking of one of his health care advisers, Gail R. Wilensky, who had long championed the cause, the position paper stated, “We must make public more information on treatment options and doctor records, and require transparency regarding medical outcomes, quality of care, costs and prices. We must also facilitate the development of national standards for measuring and recording treatments and outcomes.”

President Obama came to office strongly sharing this conviction and committed to putting it into practice. But as it happened, even the administration’s most tentative moves in this direction were met by a firestorm of opposition from the drug and medical device lobbies. This opposition would have far-ranging consequences, including, in the end, an effective ban on government even sponsoring cost-effectiveness research in health care, let alone using it as a guide for setting health care policy.

The firestorm began in early 2009, when, as part of the stimulus bill, the administration proposed $1.1 billion (or one-twentieth of 1 percent of total U.S. health care spending at the time) for research into the efficacy and safety of different medical procedures. In an accompanying report, the administration explained that the research could help eliminate costly treatments. Immediately, pharmaceutical companies and device makers pounced.

“You have to be very careful,” warned W. J. “Billy” Tauzin, then president of the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, in explaining why he mobilized his industry’s legions of lobbyists in fierce opposition to the administration’s proposal. “An arrogant staffer writing a report was about to dramatically change the direction of health care in America,” Tauzin told the Los Angeles Times, adding ominously, “I hope it is a clear warning. There are a lot of beehives out there. You don’t just go around punching them.”

Soon, the entire conservative noise machine was in full swing. Just how much of this was the result of marching orders from Tauzin and his lobby, and how much was the result of Republican ideologues seizing on what they saw as an opportunity to destroy Obama’s chances for passing comprehensive health care reform, will remain forever hard to sort out, but the effects were devastating. On January 23, 2009, the Republican Study Committee sent out an alert that Obama’s true intent was to create “a permanent government rationing board prescribing care instead of doctors and patients” (emphasis in original). “Every policy and standard,” the statement warned, “will be decided by this board and would be the law of the land for every doctor, drug company, hospital, and health insurance plan.”

Within days, more than sixty patient advocacy groups, many of them funded by the drug industry, cosigned a letter to influential members of Congress making parallel arguments, which also appeared in a Wall Street Journal editorial and op-ed piece by George Will. The American Spectator took up the task of mobilizing the pro-life movement, writing, “Euthanasia is another shovel ready job for Pelosi to assign to the states. Reducing health care costs under Obama’s plan, after all, counts as economic stimulus, too—controlling life, controlling death, controlling costs.” By early February, Rush Limbaugh was outraging and terrifying his listeners by charging that a new federal bureaucracy “will monitor treatments to make sure your doctor is doing what the federal government deems appropriate.”

Republicans and the drug industry did not succeed in killing off cost-effectiveness research at that point, but they had sent a powerful shot across the bow. The stimulus bill passed and included some provision for the research Obama wanted. But politicians on both sides of the aisle were deeply intimidated by how a once second-tier issue that enjoyed support from wonks and politicians in both parties had suddenly become the target of a death ray of demagoguery.

The message would still be ringing in their ears later that year as the national agenda turned toward comprehensive health care reform. The architects of “Obamacare” knew full well, of course, that there was no conceivable way to expand access to health care, improve its quality, and simultaneously “bend the cost curve” unless medical practice became far more driven by information about the actual costs and benefits of different treatments. They knew it wouldn’t be necessary, appropriate, or even practical to use such cost-benefit analysis to determine what specific treatments doctors could give specific patients. But they also knew that such information was absolutely necessary to guiding rational decisions, on, for example, how much Medicare should pay, or whether it should pay at all, for treatments that offered fewer benefits than lower-cost alternatives.

After all, why should Medicare pay surgeons tens of thousands of dollars to perform costly, dangerous back surgeries if research established that the patients undergoing these operations do better with low-cost physical therapies? Isn’t medical practice supposed to be driven by science? And how is the public supposed to know how to allocate health care dollars if no one even knows the value of different procedures?

Accordingly, bills introduced by Democrats in both the House and the Senate called for the creation of some kind of entity to do the necessary research. But by the summer of 2009, the death ray was back, and now packing super-high voltage that threatened the political life of anyone who stood anywhere near these bills.

We all remember Sarah Palin’s sensational talk about “death panels.” And who can forget the images of lawmakers being assaulted in town hall meetings that summer by constituents even as erstwhile “moderate” Republicans like Charles Grassley fanned the flames. What many people don’t know, however, is how this firestorm forced the administration and Democrats in Congress to cave on the very measure most necessary to improving the quality of the U.S. health care system and, by extension, making it sustainable.

During the legislative battles that eventually lead to the passage of the Affordable Care Act, Republicans repeatedly introduced amendments that would bar the government from any use of cost-effectiveness research in health care. For example, in September 2009, Republican Senator Jon Kyl introduced an amendment “prohibiting the use of taxpayer dollars to conduct cost-based research and ration care.”

Meanwhile, conservative Democrats, such as Senate Finance Chairman Max Baucus, though remaining publicly committed to the idea of government sponsoring some kind of “comparative effectiveness research,” also began introducing measures that would ensure strong industry influence over any entity conducting the research. After the August 2009 recess, Baucus introduced legislation stipulating that the research not be done by a federal agency, but rather by a nonprofit group with the drug and medical device industries well represented on its board.

At the same time, according to Brookings fellow Kavita Patel, who was then following the legislative maneuvering as a White House aide, the pressure was on all Democrats to back away from cost-effectiveness research. In an account published in Health Affairs in 2010, she recounted how

“[a]n endless stream of organizations, citizens, researchers, and thought leaders weighed in with Senate Finance Committee staff,” with at least “some” warning “of the ramifications of using cost-effectiveness in the research.”

Their lobbying was effective, especially after Republican Scott Brown was elected to the Massachusetts Senate seat vacated after the death of Ted Kennedy. At that point, the Democrats’ balance of power was shifting away, and so was any thought of holding out for an independent federal agency that would study cost-effectiveness in health care. Instead, with Baucus driving the train, Democrats found a way to capitulate that would allow them to give the opposite impression to all but those who were paying very close attention.

In its final language, the ACA specifically bars policymakers from using cost-effectiveness as a basis for even recommending different drugs and treatments to patients. In practical effect, the ACA ensures that such research won’t even be done, let alone be used as a criterion for guiding how the nearly $2.6 trillion the U.S. spends on health care each year might be put to best use. Here’s what you need to know to understand how the fix was put in behind the scenes and why correcting it must become a high priority for health care reformers.

To understand the story, you have to be familiar with a basic concept that researchers around the world use to measure cost-effectiveness in health care. It’s known as a QALY. What’s a QALY? It stands for quality-adjusted life years, and despite its technical sound, it’s based on the common sense we all use in our day-to-day lives.

Let’s start by asking ourselves what it is that we mere mortals want from health care. Of course, most of us would like it to help us live to a ripe old age. But we also want health care to improve not just the quantity, but to the extent possible also the quality of our lives. If a genie came to you and said she would grant you any wish, you might blurt out that you wanted to live to be 110. But what if she granted your wish and at the same time condemned you to living out the rest of your years in extreme pain or in a coma? Obviously, quality of life is a factor, and often a huge one, in what we want from health care.

Researchers evaluating the effectiveness of different health care practices and policies recognize that, too. Say the comparison is between two different drugs. People who take the first live one year longer in perfect health than those who don’t. People who take the second drug also live one year longer than those who don’t, but as a side effect, they also go blind. Which is the better drug? Obviously, the first one.

This reality is captured by the concept of a QALY, which weighs the gain in life expectancy that a medical intervention is estimated to bring against its effects on a patient’s quality of life. There are many different ways to do this, but a common formula, used officially by such other advanced industrial countries as Canada, the United Kingdom, and Australia, goes like this: Take each year of extra life that a medical intervention is found to produce and multiply it by a variable that reflects the intervention’s effect on a patient’s quality of life. If the intervention results in one extra year of perfect health, the value of that variable is put at 1. If it results in something less than one year of perfect health, the value of that variable is put at some number less than 1.

If we apply this formula to the example above, here’s what we get: Because the first drug results in one year of extra life in perfect health, we multiply that year of extra life times 1, and since 1 x 1 = 1, the QALY score is 1. In evaluating the second drug, we would multiply the one extra year of life it produces by some number less than one to reflect the fact that the drug causes blindness. If that number were 0.75, we would multiply 1 times 0.75 and conclude that the second drug produced 0.75 years of quality-adjusted life.

Now right here you may be starting to have qualms about QALYs. By picking that number, 0.75, are we implying that the lives of blind people are 0.25 percent less valuable than the lives of sighted people? No, though the drug industry and many other powerful forces in our society would like you to conclude that any use of QALYs demeans the handicapped and sets them up to be killed off by death panels. But researchers use QALYs simply to rate the value of different health care interventions, not the value of people, and unless you believe that people simply don’t care if they are blinded or otherwise disabled by a medical practice, that’s surely appropriate.

In practice, interventions that help people to overcome or deal with their disabilities will score highly in QALYs, including interventions that elderly people with chronic disabilities particularly want and need. Writing in the New England Journal of Medicine, researchers Peter J. Neumann and Milton C. Weinstein note that populations with more impairment have more to gain with effective interventions, and that therefore interventions that benefit these populations will score high in QALY per dollar.

Of course, there are many reasons why people might legitimately argue over just how much to discount the value of a drug that produces blindness. Is 0.75 is the right number to use, or maybe 0.85? Who can say exactly how valuable it is to be able to see? Many studies show that humans tend to both overestimate how much they’ll enjoy getting what they wish for in life and underestimate how much they’ll suffer if their worst fears come true. People who become blind may not find it as bad as they thought it would be before they lost their sight.

Which is all quite fascinating, and a reason why we can’t just turn the whole matter over to experts, let alone computers. But certainly the right number to use in evaluating the second drug is some number less than 1, because otherwise we’d be ignoring the fact that most people do care if a pill makes them blind. (Would you?)

Whatever the philosophical and process issues involved in estimating QALYs, they pale in moral difficulty compared to a stance in which we simply ignore the full health consequences of health care. The concept of getting the most years of quality life for the least cost clearly captures what we all want from health care, including in our personal lives. Without the use of QALYs or some equivalent measure, measuring cost-effectiveness in health care is simply impossible.

And that brings us back to the Affordable Care Act. The ACA established the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, and gave it the mission of doing so-called “comparative effectiveness” research. But in so doing, it specifically forbids PCORI from using QALYs, or anything like them. The statute stipulated that PCORI “shall not develop or employ a dollars per quality adjusted life year (or similar measure that discounts the value of a life because of an individual’s disability) as a threshold to establish what type of health care is cost effective or recommended.”

More broadly and pointedly, it also states that the secretary of health and human services, who oversees Medicare, Medicaid, and the soon-to-be-up-and-running exchanges for private health insurance, “shall not utilize such an adjusted life year (or such a similar measure) as a threshold to determine coverage, reimbursement, or incentive programs.”

The implications of this language are far reaching, and explain why PCORI’s executive director so emphatically asserts, “You can take it to the bank that PCORI will never do a cost-effectiveness analysis.” As long as using the concept of a quality-adjusted life year is forbidden, along with “similar measures,” there is no way to measure the cost-effectiveness of any given drug or treatment. And that’s just what the big drug companies and medical device makers wanted all along.

Taken literally, it means that it is impossible for health care policymakers to even “recommend” one drug over another just because one costs, say, $1 million per pill and produces blindness as a side effect and another costs only $10 and leaves you with your sight intact.

Other language in the ACA ensures that it will be taken literally. The statutes that govern PCORI, for example, establish it as a nonprofit organization and then specifically require that “members representing pharmaceutical, device, and diagnostic manufacturers” are guaranteed seats on its board and allowed to serve on its expert advisory panels. Today, for example, PCORI’s board includes representatives from Pfizer, the world’s largest drug company; from Medtronic, a $16.2 billion manufacturer of pacemakers, stents, and other medical devices; and from a “patient advocacy” group called Friends of Cancer Research, whose funding derives from such Big Pharma players as Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, AstraZeneca, and GlaxoSmithKline.

The ACA also stipulates that scientists doing research under contract with PCORI may not publish their findings unless PCORI determines that the research is “within bounds”—the meaning of which, of course, the board itself gets to decide. If PCORI’s board deems it out of bounds, both the offending scientist and his or her institution are banned from receiving any other grant for a period of not less than five years, which for many scientists who specialize in evaluating the quality of health care would be a career ender.

Welcome to the real politics of health care.

How do we go forward? Explaining what’s at stake to the American public will not be easy. Every penny of that $750 billion the Institute of Medicine says we waste every year in health care goes into someone’s pocket. And the beneficiaries of that spending are not going to be quiet, from millionaire cardiologists performing unnecessary stent operations to drug and medical device makers peddling products that cannot be justified.

Not only are these interest groups highly concentrated and highly motivated, they are well funded and well practiced at manipulating public opinion. At the same time, even though prices in the U.S. health care system are primarily determined by a combination of market concentration, political manipulation, poor information, and sheer inefficiency, many citizens are predisposed to assume that more expensive treatments are always better than cheaper alternatives. And so, when told that “faceless bureaucrats in Washington” are busy putting a number on the dollar value of their lives in preparation for “rationing” their health care, they do indeed fear that “death panels” will decide who lives and who dies.

For those truly committed to the cause of health reform, overthrowing the ban on cost-effectiveness research now must move high on the agenda, and it requires clearly and forthrightly explaining what it really is and why it’s essential to everyone getting the best care possible. I have done the best I know how here to explain what’s going on and what’s at stake in ordinary language, but I certainly don’t have it down to a sound bite. Others must also try.