George Cottrell’s arrest was hardly noticed at the time, especially in the United States, and it appeared even in the court documents that his subsequent cooperation with federal prosecutors pertained to the crimes for which he had been indicted, which had no obvious relationship to the Russia investigation. Before long, however, we may all know his name and his story, and he could wind up being a key figure in the downfall of Donald Trump.

You’ll have to go behind a paywall to find out how George Cottrell survived his time in a U.S. prison. He was arrested at O’Hare International Airport on July 22, 2016, the same day that Julian Assange did his major dump of hacked emails from the Democratic National Headquarters.

Seated in a dark suit with a glass of claret in front of him at lunch recently in the Sydney Arms in Chelsea, George Cottrell describes the evening of 23 June 2016 as ‘the best night of my life – something I’ll never forget’.

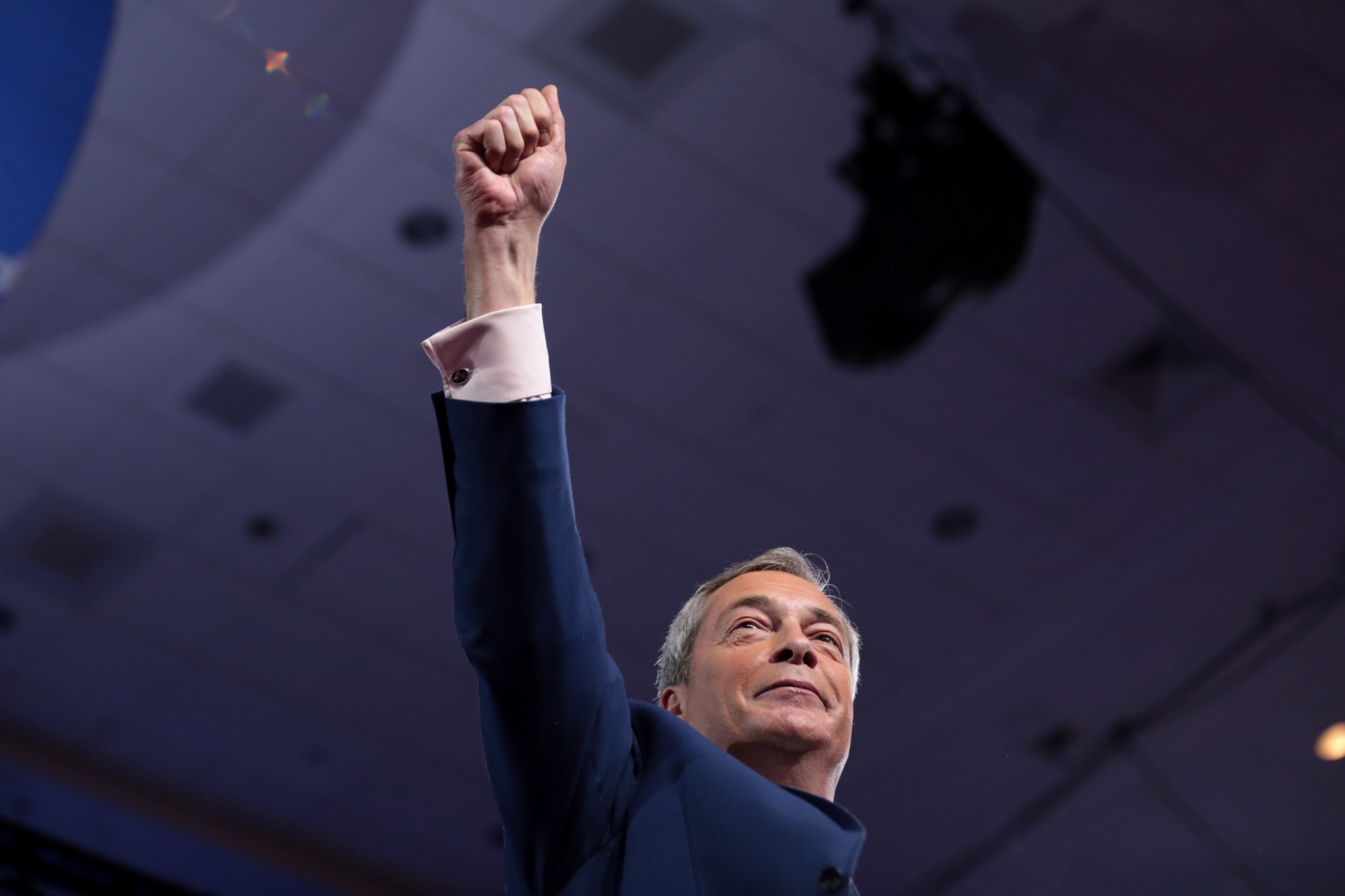

On that day of the EU referendum poll, indeed throughout that overheated political summer, Cottrell had been in the ‘jump seat’ at Nigel Farage’s side, working as his aide-de-camp, gatekeeper and campaign fixer – from booking his helicopters to letting Simpson’s Tavern in the City know that Nigel was on the way for what he likes to call a ‘PFL’ (Proper F—ing Lunch).

George is the nephew of Alexander Fermor-Hesketh, 3rd Baron Hesketh, a UK Independence Party donor, former member of the House of Lords, and Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire. He was 22 years old when the Feds intercepted him at O’Hare, seized his phone and laptop, and charged him with twenty-one counts, including blackmail, dark web money laundering, conspiracy, and wire fraud. He had been traveling in the company of Nigel Farage and his entourage as they sought to return home to England from the Republican National Convention in Cleveland, Ohio.

Understandably embarrassed, Mr. Farage sought to distance himself from his aide-de-camp.

After the arrest, Farage called Cottrell a “22-year-old unpaid volunteer and party supporter” and said he knew nothing of the “series of allegations” that had been lodged against him.

Of course, it’s highly doubtful that Farage was wholly ignorant of Cottrell’s criminal activities, and it’s more certain that Cottrell knew some unsavory things about Farage and the players behind the Brexit campaign. I suspect he used that to his advantage as he immediately offered to become a cooperating witness.

A court document filed by the prosecutors in February – which has not previously been reported in detail – advised the judge in the case to offer Cottrell a light prison sentence because he had been willing to “provide federal agents additional information after his arrest”.

Cottrell ultimately pleaded guilty to one count of wire fraud in a case that was unrelated to his work at Ukip. The crime was committed in 2014, before Cottrell worked for either the anti-EU party or Farage. Twenty other counts against him, including blackmail, were dismissed as part of the plea deal.

Robert Mueller isn’t the only one investigating the Trump campaign’s ties to Russia. In the United Kingdom, there are parliamentary inquiries underway that are looking closely at the Russians’ role in the Brexit vote, and it has become clear that the same players who worked for the Leave Campaign in Britain were also involved in helping Trump win the presidency. One thing investigators there have discovered is that the Russians had a keen interest in the arrest of Mr. Cottrell.

One of the Brexit campaign chiefs appeared to pass documents detailing an American law enforcement investigation to a Russian official, according to a cache of leaked emails.

The papers, which detailed a probe into dark web money laundering, were apparently shared with the Russian embassy in London by Leave.EU executive Andy Wigmore. They concerned the arrest of Brexit financier George Cottrell, who was seized at an airport on the way home from the Republican convention in 2016 where Donald Trump had just been nominated as the presidential candidate.

Cottrell had been at the convention in Cleveland with his boss Nigel Farage, who dined with Roger Stone and met a string of other Republican operatives and elected officials.

Parliament has discovered that key Leave Campaign figures Andy Wigmore and Arron Banks not only coordinated their efforts with the Russians but lied to them under oath about the nature and extent of their contacts. Mr. Cottell seems to have been an important part of their conspiracy:

A Daily Beast investigation of Cottrell revealed that he had a series of online links to small banks that were part of the notorious Russian Laundromat scam, which allowed dirty money to be shipped all over the world. A UKIP insider wrote that it was his knowledge of the “murky and complicated world of shadow banking” that “landed Cottrell an unpaid role” in the party.

UKIP officials said they had no idea that Cottrell had touted himself as a money launderer on a TOR black market site until they saw the indictment against him.

Arron Banks was a co-founder of the Leave.EU campaign whose generosity toward the effort made him the largest political donor in the history of British politics. We now know that the day after Leave.EU launched its campaign, the Russian ambassador to the UK introduced Mr. Banks to a Russian businessman who “offered Banks a multi-billion dollar opportunity to buy Russian goldmines.” We know that Mr. Banks traveled “to Moscow in February 2016 to meet key partners and financiers behind a gold project, including a Russian bank.” And we know that Banks maintained and “continued extensive contact” with Russian embassy figures “in the run-up to the US election when Banks, his business partner and Leave.EU spokesman Andy Wigmore, and Nigel Farage campaigned in the US to support Donald Trump’s candidacy.”

Despite the unfortunate incident at O’Hare airport, Farage and his crew didn’t come away empty from their time at the Republican National Convention. And they may have Farage’s drinking problem to thank.

Farage, who hours before had witnessed the New York business mogul’s official presidential nomination by the Republican Party, wanted one last round of drinks at 4:30 a.m. in his hotel bar before retiring for the night.

He and an associate sat down at the bar and happened to strike up a conversation with Gov. Phil Bryant’s aide John Bartley Boykin, who was staying at the same hotel. Boykin, who accompanies Bryant to nearly every public or private function, suggested that the popular British politician visit Mississippi.

Farage, “amid the alcohol-fueled joviality” of Trump’s nomination, assumed the invitation would not come to fruition, Banks writes.

A formal invitation to visit Mississippi from Gov. Phil Bryant’s office arrived the next day, setting the stage for Farage’s memorable introduction by Donald Trump at a Jackson, Mississippi campaign rally on August 23, 2016.

By the time Farage stepped off his plane on Aug. 23 at the Jackson-Evers International Airport and into Gov. Phil Bryant’s blacked out SUV, he and two of his aides had drunk four bottles of wine.

Before the three boarded their plane at London Heathrow, they drank three “filthy cappuccino martinis” at the request of Farage, Banks writes. The team landed in Jackson “eleven hours and four bottles of red wine later,” he says.

While Mr. Banks was in Mississippi, he convinced Gov. Bryant to help him establish a relationship with the University of Mississippi’s research park.

Cambridge Analytica whistleblower Brittany Kaiser testified before British Parliament this week that Banks’ insurance company Eldon Insurance Services and his data firm Big Data Dolphins was working with “a data science team at the University of Mississippi” after Banks cut off data contract negotiations with Cambridge Analytica.

Kaiser claimed the University of Mississippi researchers could have held or processed U.K. citizens’ data outside of the country, a possible criminal offense.

Since that time, Gov. Bryant’s relationship with the Brexit crew has only grown stronger:

Bryant has since hosted the Brexit leaders in Mississippi several times and has regularly appeared on Farage’s radio show in London.

During an Ole Miss football game on Nov. 2, 2017, Bryant was in the stadium’s luxury skyboxes with Banks, Wigmore and British billionaire Michael Ashcroft. Lord Ashcroft even fired off the on-field cannon used when Ole Miss scores a touchdown, according to his Twitter post.

Lord Ashcroft is another shady character who is best known at this point for gloating over his successful tax evasion.

As of now, the American media has not seized on this web of conspiracy and criminality, largely because it is hard to understand and even harder to report. At the moment, it is a white hot story in England, however, as it has more than adequately provided a smoking gun to prove Russian involvement in the Brexit campaign. But it’s a web that leads everywhere, including into Cambridge Analytica and the whole Facebook controversy, and including into the Trump campaign and the governor’s office in Mississippi.

It’s still unclear how instrumental George Cottrell’s July 22, 2016 arrest, seized phone and laptop, and cooperation with U.S. prosecutors has been or will be in unraveling this mess, but there’s a reason that his confederates went running to the Russian embassy to keep them abreast of the charges against him.

The main difference between Mueller’s investigation and the parliamentary inquiries in Britain is that we’re getting almost no information from Mueller. But it’s doubtful that Mueller doesn’t know as much or more than what parliament has learned. And I suspect a time will come when, one way or another, Mr. Cottrell will tell us his story.