In the months before the 2016 election, corporate concentration broke through as a salient issue in Washington for the first time in decades. Building on years of work published in the Washington Monthly by Barry Lynn, Lina Khan, Phillip Longman, and others, mainstream Democrats began speaking of America’s monopoly problem, linking it to rising inequality and falling rates of entrepreneurship. That April, Barack Obama’s administration, after years of lax antitrust enforcement, published a white paper documenting the growing dominance of large firms over the economy and its baleful effects on economic opportunity. On the campaign trail, Hillary Clinton became the first major presidential candidate in decades to advocate tougher antitrust enforcement.

Donald Trump, Clinton’s rival for the presidency, also spoke out on the issue that year. After AT&T announced plans to acquire Time Warner, Trump declared in October 2016 that the proposed merger would be “too much concentration of power in the hands of too few,” and promised to block it. Trump spoke against the monopoly power of companies like Amazon, Facebook, and Google. Shortly after being elected, Trump’s Department of Justice moved as promised to block the AT&T/Time Warner deal, one of the government’s most ambitious merger cases in 40 years.

Observers across the political spectrum applauded, warning that the merger would lead to fewer outlets for independent programming and too much concentrated power over the information environment. But many became critics after the judge criticized the prosecutors for resting their case on a highly technical, unprovable claim that the merger would harm consumers, and ruled in favor of the merger.

Still more disillusioning to antitrust reformers was the question of Trump’s motives.

Trump had a long history of criticizing CNN, which was owned by Time Warner. He had even once publicized a doctored video that depicted him body-slamming the CNN logo. After the DOJ brought its suit, a New Yorker investigation confirmed that Trump had personally told deputies to have the merger blocked as punishment for CNN’s unfavorable coverage.

Adding to doubts about the sincerity of Trump’s opposition to monopoly, the DOJ soon afterward waved through Disney’s acquisition of the entertainment assets of 21st Century Fox, a deal that drastically consolidated media markets. Though Trump’s preferred network, Fox News, was left out of the deal, the sale inflated Fox chairman Rupert Murdoch’s personal fortune by billions of dollars, for which Trump offered his personal congratulations.

The favoritism bore an obvious resemblance to an infamous episode from a half century earlier: Richard Nixon’s interference in International Telephone & Telegraph’s purchase of the Hartford Fire Insurance Company, at the time the biggest merger in American history. In June 1969, when the DOJ was preparing a suit to block the sale, Nixon ordered his deputy attorney general to back off. As reporters soon uncovered, ITT’s CEO was a close friend and ally of Nixon’s, and the company had secretly contributed $400,000 to his reelection campaign.

If such a scandalous quid pro quo is historically rare in antitrust enforcement, Democrats, too, sometimes exercise prosecutorial discretion. Lyndon Johnson held up the antitrust review of a bank merger until the owner of one of the banks, who also ran a newspaper, agreed to give him more flattering coverage. Despite the urging of Federal Trade Commission officials, Obama declined to take antitrust action against Google, which had forged a close partnership with his administration. Google’s employees had contributed more to his reelection campaign than almost any other company.

But the selective application of the law was endemic to Trump’s antitrust operation. Makan Delrahim, the head of the DOJ antitrust division under Trump, gestured toward populist criticisms of the long-standing antitrust status quo. But in summer 2019, when Sprint and T-Mobile were working toward a merger that would reduce the number of major cell service providers from four to three, Delrahim not only declined to intervene but actively worked to ensure that the deal went through, lobbying other regulators and members of Congress and fighting an antitrust suit brought by a group of states. His motives were apparent: Sprint is majority owned by SoftBank, and SoftBank’s chairman, Masayoshi Son, is a known ally of Trump’s.

By contrast, shortly after Trump posted several furious tweets about an agreement Ford, BMW, Volkswagen, and Honda had made with California to set stricter emissions standards than those proposed by the White House, Delrahim opened a plainly baseless antitrust investigation into the four companies. The New York Times editorial board called it a “cruel parody of antitrust enforcement,” and the policy writer David Dayen observed that “the notion that the automakers conspired with each other to raise fuel standards in a bid to limit competition is a joke.”

As Matthew Buck and Sandeep Vaheesan of the Open Markets Institute documented, Delrahim also made a habit of helping out large corporations by involving the DOJ in antitrust lawsuits where it wasn’t a party. On several occasions in office, he issued amicus briefs defending tech giants like Apple and Comcast facing antitrust lawsuits from states and consumers.

In June 2020, the career DOJ official John Elias revealed during congressional testimony that the department had devoted major resources to other dubious investigations. Attorney General Bill Barr, for example, ordered a series of unfounded antitrust investigations of cannabis companies. Probes into “Big Pot” accounted for 29 percent of the antitrust division’s merger investigations.

Trump’s relationship with the FTC, which has major antitrust powers, reveals a similar pattern. After Trump finally appointed someone to chair the FTC in 2018, his choice, the attorney Joseph Simons, announced that he would become far more aggressive on antitrust. But he essentially did the opposite, presiding over a largely passive period for the agency. Trump’s FTC filed about 21 total merger enforcement actions per year, only slightly more than under the Obama and George W. Bush administrations.

Trump’s FTC won only one major decision against a monopolist in its first three years: the chipmaker Qualcomm for its dominance of critical components in cell phones. Yet after a district court ruled in favor of the FTC, this lone success was torpedoed by internecine squabbling. When Qualcomm appealed, the DOJ took the unheard-of move of intervening against the FTC, filing a motion defending Qualcomm. Delrahim, as it happens, was outside counsel for Qualcomm for many years prior to his federal service, though he officially recused himself from the case. Qualcomm won on appeal in 2020.

To their credit, during Trump’s final months in office, regulators filed two historic lawsuits against tech monopolists: one against Google for its dominance of the search engine market, and another against Facebook calling for it to divest WhatsApp and Instagram. (The Google search case went to trial in fall 2023.) Though advocates worry that those cases, like the case against Time Warner and AT&T, were imperfectly designed by a chaotic administration, they nevertheless helped reestablish a more confrontational enforcement paradigm on antitrust.

Democrats became increasingly focused on combating monopoly during Trump’s time in office. U.S. Senators Amy Klobuchar, Al Franken, Cory Booker, and Elizabeth Warren delivered soaring speeches about confronting monopolies and introduced new legislation to strengthen antitrust law. In 2019, the House Judiciary antitrust subcommittee opened a sprawling investigation led by Democrat David Cicilline that documented how Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google use their monopoly power to threaten free enterprise and democracy. On the campaign trail in 2020, the field of candidates competed on who had the best anti-monopoly plan.

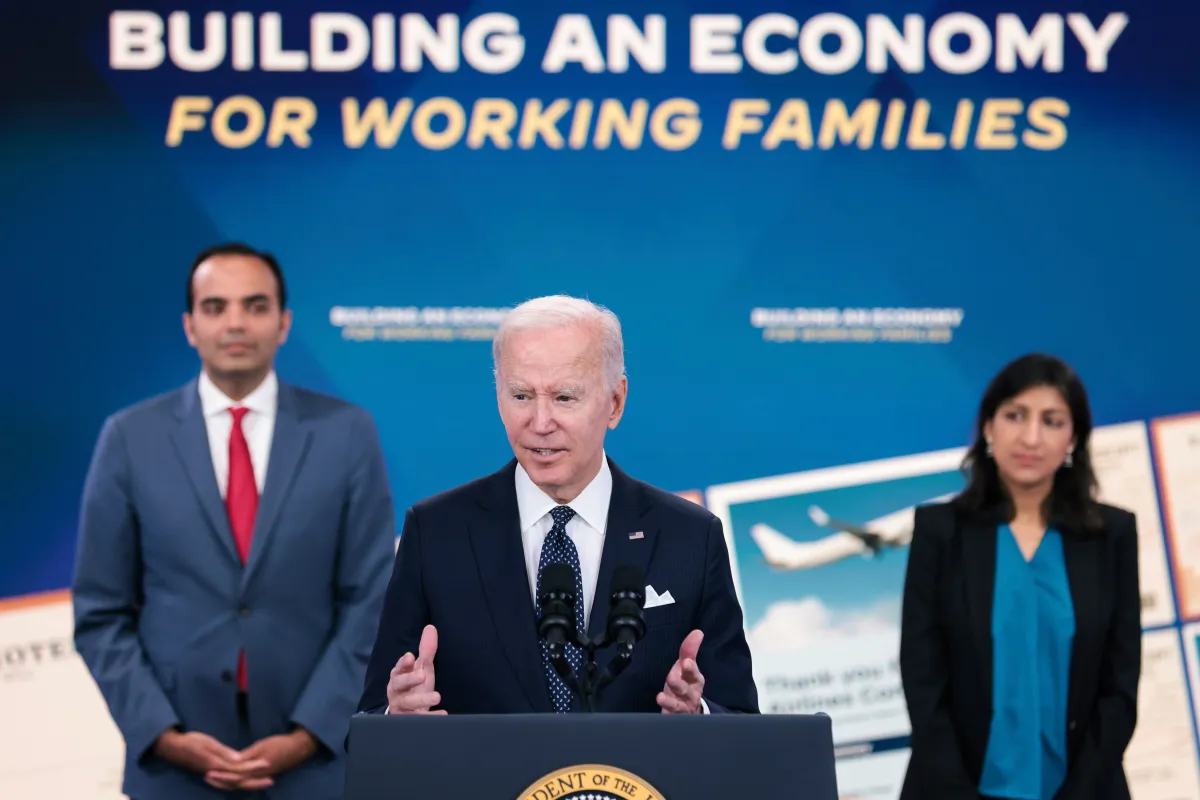

Biden was not at the vanguard of this movement in his party, but his campaign’s policy papers included promises to confront monopolies. Then, after he won the election, Biden committed to the cause like no other president had in modern times. He appointed one of the movement’s brightest and most aggressive reformers, Lina Khan, to run the FTC, as well as other fierce critics of corporate concentration in key posts, including Jonathan Kanter, who took over the antitrust division of the DOJ, and Tim Wu, who became a key economic adviser inside the White House. Six months after taking office, Biden issued a whole-of-government executive order that called on 17 different government agencies to take 72 actions to foster competition and protect consumers against monopolies. As a result, agencies like the FTC, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, and the Food and Drug Administration have cracked down on public scourges like price gouging, noncompete contracts, and banking-related junk fees, and created new rules to make consolidated industries like the hearing aid market more competitive.

Under Kanter and Khan, the DOJ and FTC have also filed far more ambitious antitrust investigations than any administration in decades. Last summer, an investigation into several food production conglomerates over wage suppression and collusion resulted in an $85 million settlement, one of several successful DOJ investigations into no-poach and wage-fixing schemes across the economy. In December, the FTC successfully blocked the medical data firm IQVIA’s attempt to monopolize the business of advertising to doctors through the purchase of an ad tech company called DeepIntent. And in January, a judge sided with the DOJ in its suit against a JetBlue-Spirit merger, the first successful prosecution of an airline merger in 40 years.

The effect of a more aggressive posture from regulators goes beyond favorable court rulings: Under the threat of litigation, Amazon, Lockheed Martin, Berkshire Hathaway, and the chipmaker Nvidia were some of the companies to back off multibillion-dollar acquisitions of smaller firms. Biden’s regulators filed a record 50 antitrust enforcement actions last year, and mergers dropped to a 10-year low.

Trump’s regulators, like all administrations of the past 40 years before Biden, argued cases mainly on the narrow basis of harms to consumers. But Khan and other reformers argue for reestablishing an interpretation of antitrust law that’s more expansive than this “consumer welfare standard.” Under Biden, regulators have rewritten the government’s lax merger guidelines and have often focused their legal strategy on the harms done to producers as well as consumers. For example, in October 2022, regulators secured one of the most important victories of the Biden era with a successful challenge to a merger between Simon & Schuster and Penguin Random House, which would have cut the number of major publishers in the U.S. from five to four. Prosecutors focused their arguments on how the industry’s consolidation hurts authors, not consumers; by winning with that argument, they established the precedent that antitrust cases can be won by proving harm to both workers and independent contractors.

The selective application of the law was endemic to Trump’s antitrust operation. But under Biden, the government has filed far more ambitious antitrust investigations than any administration in decades.

The federal judiciary is largely accustomed to ruling leniently on antitrust cases, and Biden’s regulators have also lost several important cases, including lawsuits against Meta’s acquisition of the virtual reality firm Within and Microsoft’s acquisition of the video game company Activision Blizzard. But even in losses, arguments advanced by prosecutors have helped establish useful precedent. For example, in the Within case, the FTC argued that a monopolist’s acquisition of a budding company in the industry, rather than a well-established competitor, can breach antitrust law, and that a large corporation’s investments in a market it’s not already in—virtual reality, in this case—can harm competition. In his decision, the judge acknowledged both arguments as valid in principle, marking the first instance since the 1980s that a court has endorsed such arguments.

Moving away from the consumer welfare standard will be especially important for regulating tech platforms like Google and Amazon that offer free or cheap services to consumers while gouging the businesses that have no choice but to market on their platforms. Last year, regulators announced two more long-awaited, major tech lawsuits. The first, another against Google, charges the company with maintaining a monopoly over online advertising by controlling the tools and digital auction systems companies use to place ads. Google siphons ad revenue from publishers, making the business of journalism unsustainable. The second investigates Amazon’s coercive behavior toward online merchants, including its practice of punishing businesses that sell on its Marketplace for offering lower prices elsewhere. These and other important antitrust cases—for example, the FTC’s investigations into the cartel behind hospital drug shortages, a private equity firm’s roll-up of anesthesiology providers, and Big Tech’s investments in artificial intelligence companies—will become the responsibility of whichever administration wins in November.

Much of the business world is betting it will be Trump. After a long dip in merger activity, the monopoly researcher Matt Stoller noted the announcement of several high-value mergers this winter: Exxon made an offer to buy the shale producer Pioneer; Alaska Airlines and Hawaiian Airlines proposed combining; Chevron is buying Hess; and more. “I don’t mean to say that Trump will win,” Stoller wrote, “only that Exxon, Humana, Chevron, et al. are betting that they might find a far more favorable climate when their deal goes to trial.”

In other words, monopolists know that the self-proclaimed first businessman president was a lot more bark than bite on enforcement. Maybe that would change a second time around: Conservative think tanks like the Heritage Foundation and the Federalist Society that are hoping to staff a Trump administration are starting to eschew the party’s market fundamentalism orthodoxy and embrace anti-monopolism. But Trump has made clear he’d use another term to punish his enemies and protect his cronies by whatever legal tools available, and there’s little to suggest that he’d staff his administration with fair-minded regulators instead of willing sycophants.

A second term for Biden, on the other hand, would ensure the meticulous prosecution of ongoing antitrust lawsuits against Google, Amazon, Apple, Live Nation, Visa, UnitedHealth Group, Exxon Mobil, Subway, Kroger and Albertsons, and others. It would also mean the furthering of Biden’s whole-of-government effort to crack down on all forms of anticompetitive behavior. In February, the CFPB announced that it’s taking on credit card comparison websites that take kickbacks from banks to move their cards up the rankings, stifling competition, and is building its own public comparison-shopping site. In March, the FTC launched an investigation into price-fixing and collusion among landlords and property managers in the highly consolidated rental market. Proposed rules that would ban auto dealers from using bait-and-switch tactics, protect small poultry farmers from deceptive corporate distributors, break up the organ donor network monopoly, and restore net neutrality are popping up across the government.

Ahead of the election, with satisfaction with the economy still low, Biden is doubling down in his war on shady pricing practices. In his State of the Union address, Biden railed against “deceptive pricing from food to health care to housing” and promised to crack down further on junk fees. “Snack companies think you won’t notice when they charge you just as much for the same size bag but with fewer chips in it,” he scoffed, and called on Congress to pass Senator Bob Casey’s recent anti-shrinkflation bill. In March, he issued a new executive order creating an FTC- and DOJ-led “Strike Force” to target anticompetitive practices across the economy, instituting new rules that slash credit card late fees from the current average of $32 down to $8, banning deceptive contracts in farming and ranching, and more. Whether all this momentum translates into real wins against corporate power will depend on who occupies the White House.