If you had to boil down the biggest question rattling through the minds of tortured Democrats these days, it’s “Why don’t voters get it?”

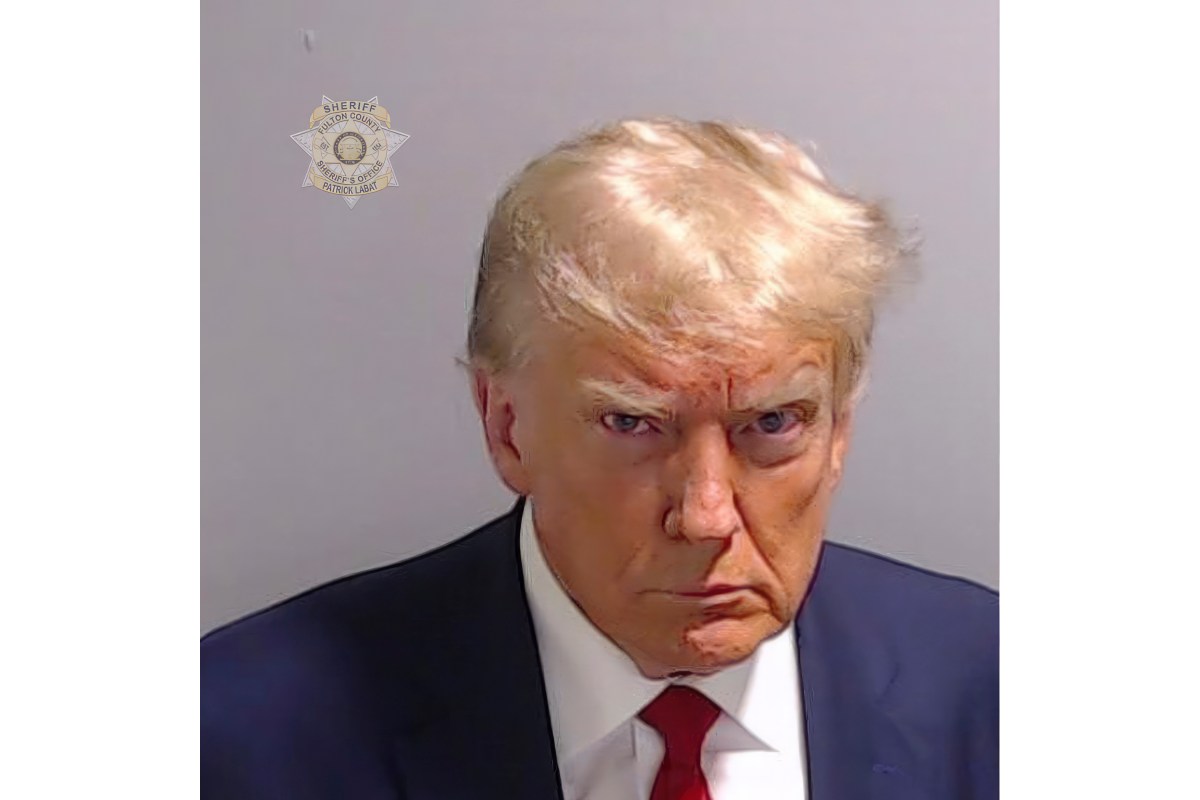

How in the name of all that is holy can Donald Trump—a man indicted on 91 felony counts—still be leading in polls? Why are people so down on a president who has passed more popular bills than anyone since Lyndon Johnson? How could it be that while jobs and economic growth are soaring, many voters believe the economy is doing worse than during the Great Recession?

In other words, when things seem so obvious, how can voters be so oblivious?

There are plenty of theories. Stephen Colbert thinks voters have become “numb”: a political callous formed by years of rubbing against Trump’s outrages. Paul Krugman argues that a lot of voter sourness is driven by extreme hatred of Democrats by addled Republicans—a phenomenon dubbed “negative partisanship” by political scientists. Scads of commentators think Biden has been weighed down by lousy salesmanship, exemplified by the now-jettisoned slogan “Bidenomics.”

But there’s something even simpler going on, something the analyst world tends to undervalue: Almost no one is paying attention.

The share of Americans who say they are following any kind of news closely dropped 13 points in the past eight years to just over one-third. And a segment of voters takes almost no notice of what’s happening at all, particularly when it comes to politics. According to studies conducted by pollster Ian Smith, up until a couple of months before an election, “people spend as little as ten minutes a week absorbing political news.” That’s 0.1 percent of voters’ time, about the same amount they spend brushing their teeth.

High-information voters—which includes the pundits we see on TV, the people who conduct polls, the folks who run campaigns, and yes, Washington Monthly readers—have a hard time fathoming just how much we stand out among Americans with our bizarrely high news intake.

Absorbing a lot of politics is not a reflection of intelligence or virtue but rather a reflection of priorities. And in this regard, the very narrow slice of Americans who qualify as high-information voters are major oddballs.

“People who work in politics consistently overestimate how much attention the average voter is giving to politics or their elected officials,” says Jim Papa, the political advisor to the White House under President Barack Obama. “They’re going to their jobs, they have to pick up their kids after school, there’s life happening. The average voter isn’t paying week-to-week attention, they’re sort of…catching it sometimes. So, when there’s a big story in Washington, like a government shutdown, maybe they’ll notice that. But they may not know the name of their congressman.”

The ten-minute-per-week figure is why, according to Ian Smith, the news event that Americans heard about the most last year—a year that included the first indictment of a former president, the rare ousting of a House speaker amidst worsening Republican dysfunction, and gruesome wars in Ukraine and the Middle East—was actually the Chinese spy balloon.

Why don’t voters “get it” about major political issues? Because most of the time, they barely know about “it.”

Why is Trump thriving politically despite his crimes? According to a YouGov poll taken six weeks ago, only half the country is aware that the court cases exist. Just 55 percent heard that he was found liable for sexual assault. Only 47 percent knew he was sued for fraudulently inflating the value of his properties. (Since the poll was taken, a judge found Trump liable for fraud, and he has been fined $450 million.)

Why do voters give Biden no credit for what he’s done? Because most of them had no idea that he had accomplished anything significant. In a February Washington Post-ABC News poll, 62 percent said he accomplished “not very much” or “little or nothing.”

As for the economy, voters living in a virtual news vacuum form their perceptions based on their lived experience. That experience is overwhelmingly dominated by prices. So, it is no wonder then that consumer views on the economy cratered during the period of high inflation and, according to the University of Michigan Consumer Sentiment survey, improved last year at almost the same time that wages finally began to outpace living costs.

The information gap helps explain a lot of current political questions. For instance, why don’t voters punish Republicans for Congressional chaos or the extreme views of House Speaker Mike Johnson? Because Americans who spend ten minutes a week on politics have no idea who represents them in Congress, let alone who the Speaker is, what Congress is doing, or which political party is responsible for which despicable acts.

This disconnect has been staring us in the face for a long time, but we tend to miss or misconstrue it. In 1992, President George H.W. Bush famously checked his watch during an audience member’s question at a debate – a moment that immediately entered the Pundit Hall of Fame of Political Blunders.

But the talking-head tsking focused on the wrong point. Bush’s mistake was not seeming aloof by checking the time. (Watch the video; you have to be really looking even to notice it.) It was misunderstanding the voter’s question. The voter asked how the “national debt” had affected Bush personally. He fumbled through a tangled answer about interest rates before the moderator rescued him by explaining, “I think she means the economic recession.”

Consider that this was a voter who was well-prepared to ask a very high-profile question on a topic dominating the political news at the time and who still used different language than an economist, politician, or high-information type would have used, and thereby mystified one of the most experienced politicians of the 20th century. That’s the kind of gulf we’re talking about between the tiny high-information sect and the rest of America.

And does understanding this gap matter? Yes. This is not only because it gives a fuller explanation for what so often seems like baffling voter behavior but also, more importantly, because it can help us all avoid sweating the small stuff.

For example, will the impeachment of Homeland Security Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas affect the vote in November? Doubtful. Few know who he is and will even notice the impeachment proceeding.

But would a Trump election subversion trial (if it ever occurs) featuring weeks of coverage finally break through to enough voters to move the needle? Probably yes. Several polls have shown Trump would shed support if he were convicted.

If there’s good news for Democrats, it’s that there’s so much relevant information for voters to gain once they get closer to November and start paying attention more than 10 minutes a week. For instance, voters know next to nothing about Trump’s authoritarian aspirations. Polling shows that they react strongly to it and will learn much more about it as the campaign unfolds.

This may not be the most satisfying answer for those wishing voters would express different reactions. But you can’t expect responses to news developments people don’t know about. Fortunately, that will change by Election Day.